DC: “Life is a Field, Not a Corridor.”

Bad Faith is one of my favourite philosophical subjects. What better breakdown of the freedom paradox (that it’s the world’s most desirable and terrifying commodity) could there be? What better way to explain the phenomena of professional personae and the other strange, self-defeating ways in which we behave?

“A load of French twaddle”, as my university philosophy professor had it? Non, monsieur!

David Cain (who also writes the introduction to the forthcoming Escape Everything! book incidentally) wrote an excellent post on the phenomenon this week:

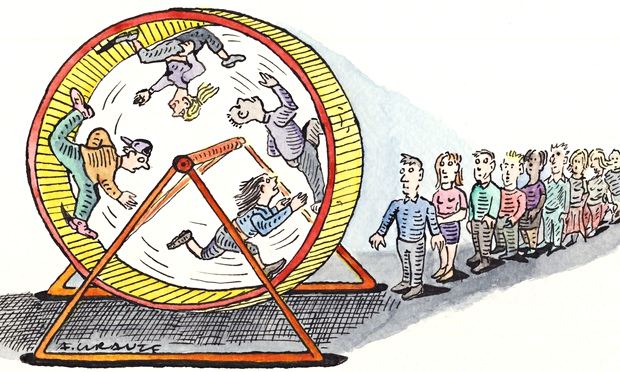

Sartre believed that we have much more freedom than we tend to acknowledge. We habitually deny it to protect ourselves from the horror of accepting full responsibility for our lives. In every instant, we are free to behave however we like, but we often act as though circumstances have reduced our options down to one or two ways to move forward.

This is bad faith: when we convince ourselves that we’re less free than we really are, so that we don’t have to feel responsible for what we ultimately make of ourselves. It really seems like you must get up at 7:00 every Monday, because constraints such as your job, your family’s schedule, and your body’s needs leave no other possibility. But it’s not true — you can set your alarm for any time, and are free to explore what’s different about life when you do. You don’t have to do things the way you’ve always done them, and that is true in every moment you’re alive. Yet we feel like we’re on a pretty rigid track most of the time.

We often think of freedom as something that can only make life easier, but it can actually be overwhelming and even terrifying. Think about it: we can take, at any moment, any one of infinite roads into the future, and nothing less than the rest of our lives hinges on each choice. So it can be a huge relief to tell ourselves that we actually have fewer options available to us, or even no choice at all.

In other words, even though we want the best life possible, if life is going to be disappointing, we’d at least like that to be someone else’s fault.

That’s Samara‘s drawing of Sartre on a plate, by the way.

★ Buy the latest issue of New Escapologist at the shop, buy our most popular digital bundle, or pre-order the book.

The Curse of Aspiration

An eye-opening column by George Monbiot. He beautifully trashes aspiration by lifting the lid on the horrible, futile, unsatisfying, pre-determined lives of the elite.

In the cause of self-advancement, we are urged to sacrifice our leisure, our pleasures and our time with partners and children, to climb over the bodies of our rivals and to set ourselves against the common interests of humankind. And then? We discover that we have achieved no greater satisfaction than that with which we began.

In 1653, Izaak Walton described in the Compleat Angler the fate of “poor-rich men”, who “spend all their time first in getting, and next in anxious care to keep it; men that are condemned to be rich, and then always busie or discontented”. Today this fate is confused with salvation.

Finish your homework, pass your exams, spend your 20s avoiding daylight, and you too could live like the elite. But who in their right mind would want to?

★ Buy the latest issue of New Escapologist at the shop, buy our most popular digital bundle, or pre-order the book.

An Escapologist’s Diary. Part 43: And For My Next Trick.

At the awards ceremony (did I mention that?) in Ontario, I met a literary agent who said a writer, as well as writing, should have a day job and a partner who works.

Regular readers of this blog will not be surprised to hear me disagree.

The idea presumably is that day jobs and working partners are a “double lock” against complete professional and financial failure, and perhaps that the double information input from these day jobs can provide the raw material for a literary output.

I prefer to throw caution to the wind when it comes to life and work (it’s served me well so far) and to just get on with things in terms of writing. When I have a job, my prevailing thoughts are “this is an appalling expectation” and “why can’t I just be left alone to get on with my stuff?” none of which is very productive. As for a working partner, I wouldn’t wish a job on an enemy let alone the person I’m uniquely squiggly about.

Regardless of my thoughts on the matter it’s starting to look as though my partner and I will be following the agent’s advice to some extent.

A term of my wife’s immigration to Britain from Canada is that her spousal sponsor (that’s me!) earns £18,600 per year. Without revealing the full moth-ridden shame of my personal finances to you, dear reader, I do not usually make £18,600 per year. We live well and have never been in debt but that’s not enough for the British government. They want to keep Bohemian types off these shores, and that includes my life partner. Honestly, they don’t know what they’re missing. She’s fab!

Fortunately, we’ve found a rare loophole that (assuming the Tory vermin don’t close it this year) will allow Sam and me to share the burden of earning the £18,600. Sam’s looking for a j-o-b and I’ll be relying largely on short-term contract work like some sort of hipster-for-hire.

We can’t depend on our (by most standards quite substantial) savings because the value of savings is subject to an equation designed to make it look like a pittance. We can’t depend on the kind of literary or arty schemes I’m known for either. I could reframe my entire artistic output as self-employment by keeping detailed accounts, but the criteria for this is confusing and contradictory so I’m terrified of Sam’s visa being rejected on a technicality.

So it looks like Robert W, self-styled master Escapologist, has little choice but to OBEY and must knuckle down for a spell. No more getting up at 11, no more boozy breakfasts, no more writing or chatting into the we small hours. A crushing blow really, to have the shackles put back on so mercilessly despite thinking we’d got things all figured out (the £18,600 financial requirement has only existed since 2012).

We have for a while felt like Winston and Julia in Nineteen Eighty Four, cast asunder in a gigantic, unforgiving mechanism. But we’ll not dwell on that. Let this diary be cheerful.

I mentioned in the last thrilling installment that I’ve accepted a one-month contract at a university. It’s going surprisingly well. Today will see my twelfth working day draw to a close: almost halfway through. The campus is rather beautiful, abundant with wildlife; my temporary colleagues are a very good-natured bunch; and (I can’t quite believe I’m writing these words) I’m enjoying the commute.

After a short and barely-noticeable jaunt on the tube, I take a half-hour train ride into the countryside, followed by a twenty-minute brisk walk to the campus. I like trains and I like walking, so it works out nicely. I wouldn’t be so chipper about this if the train were a crammed inner-city commuter one or if the walk was much longer or less scenic. I’ve been lucky.

Feelings of “that I have to do this is a fucking outrage” are mitigated by the fact that the job is temporary and that it’ll be nice to have some extra cocktail money anyway. I’ve also started, rather uncharacteristically, keeping a nature diary, for which twice-daily walks in the countryside provide ample fodder.

I have secret hopes of winning less desk-bound, more arty contracts. A new artist friend is good at raising money and seems willing to hire me in some capacity. Meanwhile, poor Sam’s applying for all manner of curious employment to shoulder her half of the burden.

For all my cheerful (stoical?) approach to the situation, being forced into work could barely come at a worse time. My book, Escape Everything, is due for publication quite soon. Received an early sample of the cover art yesterday evening and it looks utterly marvelous. I need to be available for last-minute edits and, afterwards, for any promotional work and public events. As much as anything though, it’s embarrassing to have written the bible of Escapology only to fall into mandatory (albeit brief and fairly undemanding) employment almost immediately. I hope people see how extraordinary my circumstances are.

Still, all this at least provides material for the next few issues of New Escapologist. Watch in awe, ladies and gentlemen, as the Great Roberto escapes his toughest predicament to date! This surely is my “Chinese Water Torture Cell” moment. Let’s see if I can escape.

★ Buy the latest issue of New Escapologist at the shop, buy our most popular digital bundle, or pre-order the book.

Hardworking

Interesting topical thoughts about the nature of work in Zoe Williams’ column today, with reference to a new survey of attitudes to working hours:

these figures point to the same conclusion: people work extremely hard when they can’t live any other way, and steadily less hard – or wish they could work less hard – when they can afford to.

It contains a thought about the modern use of the word “hardworking” used frequently by twats in the government:

the new consensus about hardworking people, hardworking families, human units defined by the intensity of their effort, actually sounds, when you decouple it from whichever smooth voice whence it came, a bit Soviet. It calls to mind those glory years of post-revolutionary propaganda in which to work – particularly with your top off – was to wrest back dignity from the capital forces that had tried to steal it from you. And yet we are meant to exist in this era of self-interest, in which our sense of identity is created not by work but by consumption. It’s a totally contradictory trope: of course it couldn’t brook challenge or nuance or an honest account of what work actually means to people. It would disintegrate.

I recently read Green MP Caroline Lucas’ marvelous book about the mechanisms of parliament. She says that “hardworking” is indicative of subtle Conservative Party propaganda, in this case a deliberate and concerted attempt to “reframe” the way we perceive beneficiaries of the welfare state. Rather than see pensioners, the disabled and the unemployed as people deserving of state assistance, the Tories want us to despise them so that any cuts to their welfare will be met with public approval. The key, apparently, is to position them as lazy, selfish, non-hardworking:

★ Buy the latest issue of New Escapologist at the shop or pre-order the book.

Yearlong Caravan Holiday

we currently enjoy a richness that we could never have imagined. […] we believe that the real measure of modern success is nothing to do with your bank balance or the size of your house, but instead, the amount of free time you have at your disposal. We think disposable time, as a resource to strive for and spend, counts for much more than disposable income. You see, time is much more valuable than anything else, be it natural resources such as gold or diamonds, or a man-made commodity such as money. Time is the currency of life itself.

Reader Briony shows us a lovely news story about a family of four who got tired of their conventional life and gave it all up. They now live, very happily by the sounds of it, in a touring caravan and self-employed:

the trade-off for [a house and the income and security of a job] was that we also had the ongoing monotony of working too many hours, with not having enough sleep, and with not having enough time to spend with Amy and Ella doing the things that we know are so important for parents to do with their children: reading with them, playing with them, or just having enough uncluttered quality family time. And to cap it all, I saw Kerry on what seemed like a daily basis being psychologically and emotionally crushed under a growing pile of marking, pupil target matrices and pointless Excel spreadsheets that were being filled in because the data might one day make an Ofsted inspector happy.

[…] Reassuringly for us, this was how many of our friends and colleagues were also living. Living for the weekends, I mean. It was normal. It is normal. You see, as a culture, it seems we are almost accepting of this way of life. It’s a way of life that often seems to prioritise work and money above time spent together as a family or with friends.

“It would be interesting to find out what they decide to do after their nominal year,” says Briony. My advice? Carry on Camping. New Escapologist salutes the Meeks.

★ Buy the latest issue of New Escapologist at the shop or pre-order the book.