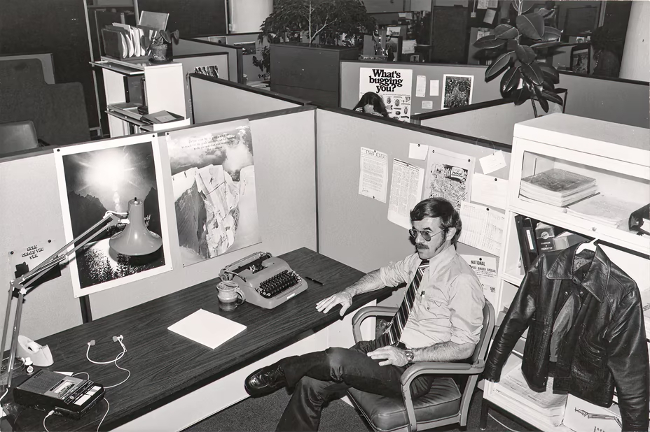

The Escapes of Chauncey Hare

Thanks to Friend Tim for sending me this Atlantic article about the office photography of Chauncy Hare.

Photography started as a hobby for Chauncey Hare. For 27 years, he worked as a chemical engineer at the Standard Oil Company of California, using his camera to escape the tedium of the office. By 1977, he couldn’t take it anymore. But before he declared himself a “corporate dropout” and committed to art full-time, Hare trained his camera on the world he hoped to leave behind.

Remarkably (though this part’s not in the article), Hare quit his job again when he stopped being a photographer to become a clinical therapist specialising in “work abuse.” Clearly, the antiwork message to Hare was the work.

Before Hare died, in 2019, he saw to it that any future publication of his work would include the following disclaimer: “These photographs were made to protest and warn against the growing domination of working people by multinational corporations and their elite owners and managers.”

There’s a book about Hare’s life work called Quitting Your Day Job by Robert Slifkin.

Letter to the Editor: How is Friend Henry Doing?

To send a letter to the editor, simply write in. You’ll get a reply and we’ll anonymise any blogged version.

Hello Robert!

My brother and I are long-time readers of your blog and applaud your efforts to avoid work.

When we speak of the ills of technology, we often refer to Friend Henry, who you mentioned was quitting the internet for good. I’m curious: how is Friend Henry doing? Have they avoided the internet since then?

Hope you’re well and enjoying home ownership in idle bliss.

Warm regards,

Reader S

*

Hello S!

Friend Henry is still going strong. He’s improbably sincere in his escape from digital technology and I do what I can to support him (which really just involves sending him an old-fashioned letter in the post every few months).

He tells me about his successes and failures in his project. A recent success was in his newfound ability to chop logs for firewood; he’s also building a tiny house of sorts and writing poetry. A recent failure was when he gave in to social pressure to buy a mobile phone, albeit an old Nokia-type thing and not a smartphone, but I don’t think he uses it much. He has certainly never messaged me from it.

In my next letter to Henry, I will tell him that you asked after him. I have tried to encourage him to write a “Notes From [his house]” column for the forthcoming print version of New Escapologist. He didn’t seem very keen when I first asked but I think my original request was for Web content; he might be more willing now that we’re talking about print. I’m not sure. I do like the thought of him writing his column by hand, Mark Boyle-style, perhaps even by candle light, filing it by post for Yours Truly to laboriously re-type.

Best Wishes, RW

Learned Helplessness

I’ve been reading books about prison. The best one so far is probably A Bit of a Stretch, the prison diaries of filmmaker Chris Atkins.

Here’s Chris Atkins on self agency, the ability to steer your own course through life:

Much has been written about whether we have a hand in our own destiny, but at least in the outside world it feels as if we have some involvement in our fate. Prison not only robs inmates of control, but also denies them the illusion of agency. They are constantly reminded that they have no impact on anything, which has long been cited as a cause of mental illness.

He goes on to describe Jay Weiss’s 1971 psychology experiments in which rats were trained to avoid electric shocks by pressing a lever. The rats became vigilant of this, but then Weiss changed the rules so that the levers no longer worked. The rats went through a period of pressing the lever regardless (“but… but.. it always worked in the past!”) and then they fell into a period of depression.

Atkins says this has a striking similarity to the effect of “call bells” on prisoners, which supposedly exist for inmates to call a guard for help or attention. Much of the time, however, their calls go ignored due to low staffing levels caused by politically motivated funding cuts.

When Atkins was in prison, the call lights on the outside of cell doors would flash ineffectively almost all of the time, their occupants becoming steadily more desperate and then hopeless.

This is known as “learned helplessness.”

Learned helplessness exists in other areas of society too: in childhood, university, jobs, hospitals, visas and immigration. It is designed to prevent escape.

Escape, hope and agency are intertwined. Dare to dream of escape, dare to hope, dare to act.

*

For ideas on how to escape, try I’m Out (formerly published as Escape Everything!) and for a shoulder to cry on, try The Good Life for Wage Slaves.

The Indulgence of Sleep

A brilliant passage from Shola von Reinhold’s LOTE, which is so far my novel of the century.

“A lack of sleep leads to fascism, you know, Griselda.” I decided it would be a good time to expound my theory: the sort of people who claim to require a few hours a night frequently happen to be morally bankrupt. This did not include people who couldn’t get a decent number of hours’ sleep because of insomnia, work or children and so on, but rather people who claim not to need it and thus exhibit their own productiveness. These people included various right-wing politicians, dictators and numerous CEOs, regularly dubbed “The Sleepless Elite” by business magazines. Implicit in their claim is that everyone in the world aught to relinquish sleep if they want to escape hardship. That you are being indulgent. Perhaps their own lack of sleep causes this way of seeing: they are seriously sleep-deprived without realising they are, and after this long-term deprivation, their capacity for empathy has dwindled.

I remember something Tom Hodgkinson said in the Idler in the late ’90s: he was responding to Tony Blair making the perennial Thatcherite claim that he doesn’t sleep very much and in fact doesn’t dream. Tom contrasted Blair’s strange boast to Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream,” arguably the most affecting and important political statement of all time.

I suppose the dictators and CEOs observed by Shola von Reinhold think they’re being stoical or independent-minded in some way with their claims to supernature, but it’s hardly inspiring to have a leader who boasts of being deprived and, in Blair’s case, unimaginative.

If you’re looking for new year’s resolutions, you could do worse than buying and reading LOTE and learning to nap.

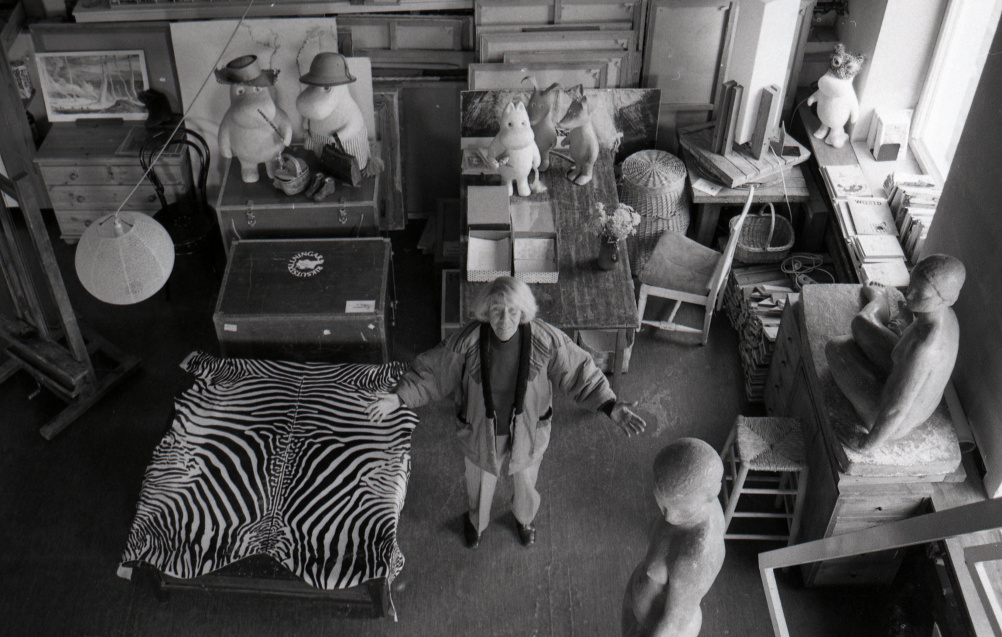

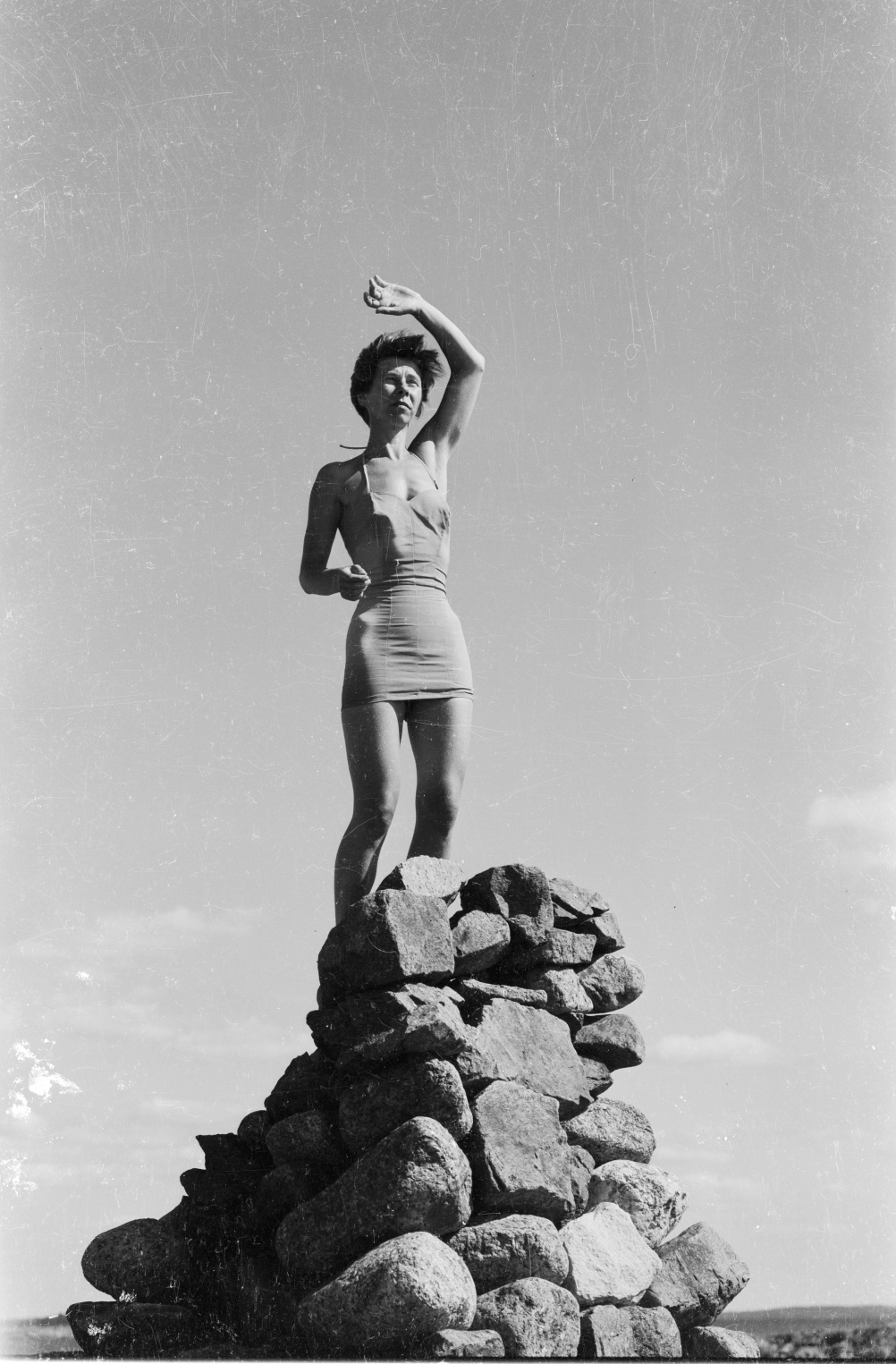

More Tove

Further to our previous post, there’s a nice documentary on YouTube about the freedom- and adventure-loving life of Tove Jansson.

There’s also the following hour of archive footage, some of which was used in the documentary. None of it is in English but if you have a big screen or a projector in your home (alas I do not) it could still provide some cheerful ambient company.

Tove Jansson: Love and Work

I recently read Fair Play by Tove Jansson.

It’s a work of fiction drawing heavily on Jansson’s later life, shared with her artist partner Tuulikki Pietilä. Together they make art, bicker playfully, obsess over movies, walk in nature, receive visitors. Sometimes they live in the city and sometimes on an unpopulated island.

In the foreword to the edition I read, Ali Smith describes the novel’s main themes as “love and work.” This is correct and it’s a fair reminder that “work” is not the true thing an Escapologist finds objectionable. For example, we’d probably value the flow and the consensual nature of small art production. It’s the submission of employment and the competitive brutality of business that we object to.

Fair Play is stuffed to brim with depictions of love and “the right kind of work.”

There’s also a collage of photographs on the inside covers, which I found relaxing to look at. I present them here along with some Escapological quotes from Fair Play (and some from my follow-up reading).

Some people just shouldn’t be disturbed in their inclinations, whether large or small. A reminder can instantly turn enthusiasm into aversion and spoil everything.

It is simply this: do not tire, never lose interest, never grow indifferent—lose your invaluable curiosity and you let yourself die. It’s as simple as that.

What was it we were so busy with? Work, probably. And falling in love – that takes an awful lot of time.

From AnOther magazine:

when you trace the secret history of [Janssen’s] life, [you discover] an instinct to live by her own rules, from childhood to her death aged 86.

From Jansson’s The Summer Book (1972):

A person can find anything if he takes the time, that is, if he can afford to look. And while he’s looking, he’s free, and he finds things he never expected.

Mari was hardly listening. A daring thought was taking shape in her mind. She began to anticipate a solitude of her own, peaceful and full of possibility. She felt something close to exhilaration, of a kind that people can permit themselves when they are blessed with love.

They sat in their separate chairs and waited for Fassbinder, their silence a respectful preparation. They had waited this way for their meetings with Truffaut, Bergman, Visconti, Renoir, Wilder, and all the other honored guests that Jonna had chosen and enthroned–the finest present she could give her friend.

And here’s the obligatory picture of Tove with her most famous creation, the Moomins.

From Finn Family Moomintroll:

Don’t worry. We shall have wonderful dreams. And when we wake up it’ll be spring.

Substacked

The New Escapologist newsletter is now administered with Substack. We used to use Mailchimp but it became increasingly rubbish so this move is long overdue.

I spent an inordinate amount of time today transferring the newsletter archive to Substack. The usefulness of this is limited when you remember that the newsletter’s content is largely a digest of these blog entries, but it somehow seemed VITALLY IMPORTANT today for me to standardise the titles and ensure each edition has its own little preview image. Job done.

The new archive is pleasant to browse should you want to. You can also leave comments beneath any edition. Fun!

Here’s where to join if you don’t already receive a monthly newsletter by email.

Gobbing Off

“Goblin Mode,” the Guardian reports, has been added to the Oxford English Dictionary.

The real story is that the term was voted in by landslide popular demand. Well, I’m glad it defeated “metaverse.”

As you probably know, “Goblin Mode” refers to “unapologetically self-indulgent” behaviour, “lazy, slovenly, or greedy, typically in a way that rejects social norms or expectations.”

Seemingly, [the term] captured the prevailing mood of individuals who rejected the idea of returning to ‘normal life’, or rebelled against the increasingly unattainable aesthetic standards and unsustainable lifestyles exhibited on social media.

I like that idling is suddenly so popular that its given rise to new terminology, but of all the fantasy creatures I’m not sure why goblins get the rap for this. Aren’t goblins quite busy and avaricious, general makers of mischief? Why isn’t it “ogre mode” or “bogeyman mode” or “swamp monster mode”? I’d say the kids don’t read enough, but Shrek’s an ogre and everyone loves Shrek.

Meh! I like lampin’ better.

Thirsting for a retreat into Goblin Mode? Try The Good Life for Wage Slaves or I’m Out, both of which are available now in paperback.

Giant Bug Monster

This human on Twitter mentions the “giant bug monster” from The X-Files “that pretends to be upper management at a call centre.”

And they share a nice behind-the-scenes photograph.

I remember that guy! The episode you’re looking for is called Folie à Deux and it’s delightful.

Is YOUR boss a giant bug monster? Try The Good Life for Wage Slaves for a shoulder to cry on or I’m Out to plot your escape.