The story of death machines

Reader Richard directs our attention to Lucy Kellaway’s History of Office Life on BBC Radio 4.

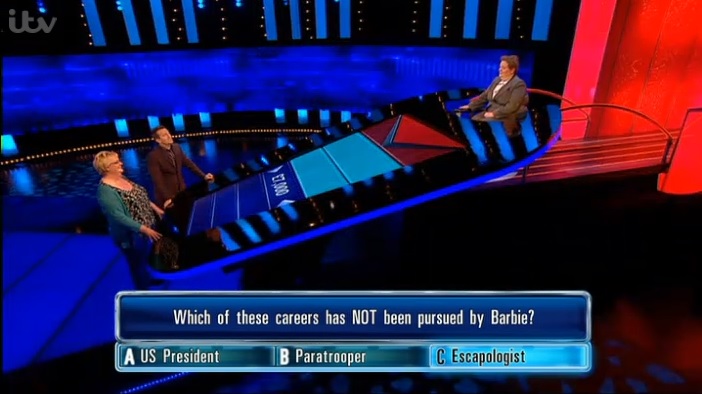

It looks good: entertaining and sufficiently critical for Escapologists. There’s a review here.

It’s an ongoing series, some episodes of which are currently live and some of which are either expired or pending. Enjoy!

Pre-order Issue Nine in print or on PDF today.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Modernist

A prospective reader asks:

Is New Escapologist a Modernist publication?

Ah! In as much as Modernism is a reaction against the Victorian penchant for clutter and decoration and empire, I suppose we are.

We favour a lean, simple, fine-tuned good life.

But we kept some of the 19th-Century ideas about manners, action, and comfort. It’s in our DNA.

I suppose New Escapologist takes influences from all over the spectrum: from the ancient world, the medieval, the Victorian and the present-day.

We’re a philosophical and aesthetic mash-up. Does this make us postmodern? Post-postmodern? I don’t know.

Simon Munnery: “Don’t worry about being modern. It’s the one thing you can’t avoid.”

Pre-order Issue Nine in print or on PDF today.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Hermits

From a review of Consolations of the Forest by Sylvain Tesson:

[H]ermits are the true radicals of our age. To retreat is to reject government bureaucracy and consumerism. Whereas those who dynamite the citadel need the citadel, the recluse simply opts out: “A repast of grilled fish and blueberries gathered in the forest is more anti-statist than a protest demonstration bristling with black flags.” Yes, the hermit may be slow and woolly-minded but he “gains in poetry what is lost in agility”.

It’s a similar stance to the one we adopt in our eighth issue, Staying In.

Why do it? To fulfil a seven-year-old dream of going to ground in a forest. To surround himself in silence. To escape ugliness, traffic and the telephone. To catch up on his reading. To see if immobility can bring the peace that travel used to. To sample an existence reduced to bare essentials. To become a hermit and find out whether he has an inner life.

Pre-order Issue Nine in print or on PDF today.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Plan A

A letter to The Guardian‘s career advice column asks for help with the safety/risk dilemma:

All my life I seem to have gone for second best – I have had dreams and ambitions but end up going for Plan B, because Plan A is scarier. Plan A is a dream of being an artist, or film-maker; but I know I am missing a lot of skills which you need in order to succeed at these kinds of jobs.

I will be job hunting soon and I am scared I will just do what I always seem to, which is panic and take some Plan B job to support myself , which ultimately I don’t like and can’t do, and which once again will take up all my time and leave me no freedom to do the things I love. I want to do what I love and get paid for it.

Doesn’t this just sum up the “employment versus life” problem? It’s the quintessential fork in the roads in choosing to become a wage slave or a free radical.

Here’s the thing. Plan B isn’t safe at all. A lifetime of servitude and dream-squelching is a far higher cost than living in a modest apartment or riding around on a rusty bicycle (if those are indeed the material fears). If you’re reporting to someone else’s office every morning and hating yourself, you’ve already failed, even if your house in the suburbs has four bedrooms in it. Plan B isn’t safe. It’s the most dangerous option, leading as it does to a life of misery.

Moreover, this particular person’s Plan A isn’t particularly risky at all. “Artist” and “Film Maker” are both real jobs. It’s not like he wants to become a professional chocolate-eater or freelance boob-squeezer.

This being said, he probably needs a firmer idea of his Plan A. He wants to become an artist and/or film maker. But what kind of artist? What kind of film maker? And is he confusing a desire to eat cake with a desire to open a bakery?

My feeling is that we shouldn’t fear this kind of risk but mitigate against it by developing a clear and flexible plan. Also, visualise the worst-case scenario: how bad would it really be to live in a modest apartment or ride around on a rusty bicycle, even for the rest of your life? Is it any worse than never, ever, doing what you want?

Pre-order Issue Nine in print or on PDF today.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Endless Goliaths

At New Escapologist, we use Escapology as a metaphor. There are others we could have used, but it just so happens I was reading about Houdini five years ago in parallel to books about Bohemia and liberty. Ah, how it all came together!

At New Escapologist, we use Escapology as a metaphor. There are others we could have used, but it just so happens I was reading about Houdini five years ago in parallel to books about Bohemia and liberty. Ah, how it all came together!

I liked how Houdini’s combination of snazzy showmanship and chiding didacticism stood in for a wider parable. That’s what I wanted to do too.

I noticed that Houdini’s performance transcended conjuring and went into the world of allegory. The restraints from which he’d escape were often topical. For example, his icebox escapes referred to the up and coming frozen food industry. The idea was that modern conveniences that posed as liberating could in fact be traps. The person on the street had observed this and Houdini appealed to her/his sense of entrapment by theatricalising the escape fantasy.

Today, I came across an expert confirmation of my thesis. Jim Steinmeyer is a designer of theatrical illusions and historian of magic. In his book Hiding the Elephant: how magicians invented the impossible and learned to disappear, Steinmeyer writes:

It wasn’t really conjuring at all, even if his novel act had been derived from the world of magicians. Houdini created his own product. The drama of his performances was the sight of the little man challenged, playing David to society’s endless Goliaths, the archetypal victim who, within the strict confines of the vaudeville turn, rose to the victor.

So there we have it. That is part of what I hope is the appeal of New Escapologist, that we show through theory, example, and good humour how these “endless Goliaths” are toppled.

Pre-order Issue Nine in print or on PDF today.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Merchandising Opportunity?

Pre-order Issue Nine in print or on PDF today.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

The lovely horrible stuff

The theme of the next issue of New Escapologist will be MONEY.

It will be released in August, titled Take the Money and Run.

In this issue — our ninth — we ask impertinent questions of an economist; discuss the idea of citizen’s income as a possible escape route for all; tap on the glass of some belljar utopias; learn how to rob a bank; hear the confessions of a serial homeowner; and examine the fine arts of malingering and truancy. All over a finely-typeset 90 pages.

We can also reveal that one of our several special guests is none other than Mr. Money Mustache, who was recently featured in the Washington Post.

You can now pre-order Issue Nine in both print and PDF.

Enjoy!

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount today.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Lonely Dystopia

There are some possible objections to the CI– and technology-driven solutions to the employment problem (by which I mean “working for a living” as the standard mode of existence).

We’ll cover some of these objections more fully in Issue Nine in August.

In the meantime, a reader writes:

I saw McAffee’s Ted presentation, and it brought me back to my 1976 high school sociology class. The teacher flashed an illustration on an overhead projector depicting what labor would look like in the future.

The illustration showed a comfortably well-off couple living in a pod-like structure that had an enormous picture window looking onto a large field of corn, an unmanned robot harvesting the field.

To me, it looked like one of the oddest and loneliest futures imaginable. I remember feeling slightly uncomfortable, even a bit repulsed, as I raised my hand and asked: “But where are all the people?”

Mcaffee’s lecture leaves me similarly perplexed and somewhat skeptical of this “utopia”, [in which] there is more time to “create”, rather than work, [and] we sit in our hermetically sealed, pod-like homes with our smiling spouses and field robots.

But of course, that is pure fantasy, and a unequal one at that. What we are more likely to see outside of the sterilized pod house are hoards of unemployed people, fighting for basic necessities, while a technician class competes for the rare chance [of] labor in such a scenario. For the most part, this utopia/dystopia is already well underway.

It’s a fair enough point. It was, after all, a dysopian novel that got this discussion rolling. And even from our position in the present day we can see the alienating effects of technologies of convenience.

The primary objection seems to be that nobody will do anything real anymore, that we’ll be thrust into a state of decadent and eternal boredom when meaningful work is removed.

My rebuttal would be twofold.

1) Meaningful work, for the most part, has already been removed. The majority of us live in cities, reaping the benefits of a minority agricultural community (facilitated by technology). Meaningful work still exists in some areas but it’s hardly the default career path. In this respect, the dystopia is already here. If we want to repair this, we can either radically back-pedal to a more meaningful pre-industrial-inspired economy or push on to a high-tech future in which CI is one possible solution to avoiding mass poverty.

2) Even if claustrosphere life were to become a mainstream option, we wouldn’t have to accept it, just as some of us don’t accept the prescribed life today. When sustenance labour or wage slavery is removed, we (as a society or individuals) can do anything. It doesn’t have to be pod dwelling. Depending on our prevailing interests, we could devote our new-found time and energy to saving the turtles, to putting astronauts on Mars, or to enslaving and depressing the former working classes in a whole new way. “We could explore space, together, both inner and outer, for ever, in peace.” More than anything, we could think outside the confines of a consumer economy. Anything.

A secondary objection seems to be that mass unemployment at the claws of sophistcated worker robots would lead to poverty and a sense of deranged competition. But the McAfee future already mitigates against that. With Citizen’s Income.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount today.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.