Ask Albert

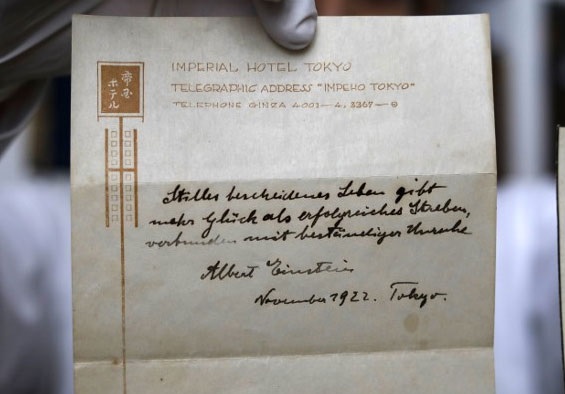

A handwritten note from Albert Einstein — originally given by Einstein in lieu of a tip to a courier — sold for a record $1.56m this week.

The note says (in German):

A quiet and modest life brings more joy than a pursuit of success bound with constant unrest.

One of the finest minds in the history of the universe concurs with our theory!

Begin With the End in Mind

I’ve never read Stephen Covey’s The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. It looks too long, too managerial, and generally like something Rimmer would read.

Doubtless it’s the sort of book to contain the odd gem or an interesting way of seeing a problem, but this is an effect that leaves me feeling like a gold prospector sifting for nuggets.

(This is precisely how I felt about the famous Getting Things Done when I finally read it last year. In this instance the useful nugget was the word “trusted”).

The 7 Habits was hugely influential and contributed significantly to the tone of modern self-help so it gets mentioned a lot. When it was came up today I found myself wondering what exactly those seven (sorry, “7”) habits are exactly so I looked them up.

Aside from the annoying discovery that I’d independently come up with Covey’s abundance mentality rather belatedly, the best truth nugget lies in the second habit: “Begin with the End in Mind”.

This struck me first as a bit “well, duh” but then it hit me like a suckerpunch.

It had never occurred to me that many people (perhaps even most people?) do not “begin with the end in mind”.

Suddenly, the behavior and decisions of so many people I’ve met over the years made sense. People who binge as soon as pay day rolls around. People who think that checking themselves into wage slavery is a sustainable solution. People who hoard. People who are disorganised. Above all, people who discount the future.

You can probably see how this applies. For example, if someone in receipt of a £1,500 pay cheque had a reasonable, pragmatic, non-punishing idea of how they want their finances to look by the end of the month (e.g. all bills paid, a reasonable amount spent on fun, a minimum of £300 left over for savings) then they wouldn’t start pissing the new income so spectacularly up the wall on Day One.

In the case of being disorganised, I’d sometimes look at a spreadsheet put together by a colleague — multiple sheets scattered across a single workbook, coloured cells, bold text, complicated filters, cells formatted so that phone numbers can’t begin with a “0” — and wonder about the decisions that led to such a mess. I’d think “is this what you wanted your system to look like?” I mean, it didn’t just happen: you clicked on “bold,” you put weird formatting on those cells.

And man oh man, does this apply to minimalism. “Have nothing in your homes that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” is the maxim. Having nothing in one’s home except for the useful and the beautiful is the “end” one must “have in mind”. So when looking at the range of lovely products available to buy, or when given a gift or presented with the opportunity to take something for free, one needs to wonder if it contributes to or detracts from that end.

Some of us probably do this instinctively, but many, I suspect, do not. Covey writes:

It’s incredibly easy to get caught up in an activity trap, in the busy-ness of life, to work harder and harder at climbing the ladder of success only to discover it’s leaning against the wrong wall. It is possible to be busy — very busy — without being very effective. People often find themselves achieving victories that are empty, successes that have come at the expense of things they suddenly realize were far more valuable to them.

It’s sort of bizarre that people fall into this trap so often (or, if we’re being brutal, at all). It’s as though they haven’t worked out that actions have consequences (or that the desirable consequences require specific actions) and instead allow their listing autopilot to drift them into a tempest or throw themselves into performing a host of unhelpful, unrelated actions. Why?

I had an idea a few months ago that I’d quite like to live among a few leafy houseplants so that I might feel a bit more like a monkey in Rousseau painting. What I did next was visit a florist where I acquired a couple of leafy houseplants and I took them home. What I did not do was enlist in a dance class, rub my body down with a prone Cocker Spaniel, or ring up the Natural History Museum to complement them their famous sauropod skeleton. The reason I did not do these things is because they had nothing to do with my envisioned “end” of living among leafy houseplants.

If I found myself performing all of those crazy actions “in pursuit” of fulfilling my house plant ambition, I’d like to think that at some point I’d stop the madness and say “Why am I doing this?”

Which is a good question to ask oneself quite often, really.

Maybe a fault in Escapology is that it assumes people tend to function with an end in mind where, in fact, so many do not.

★ Please, please, please support New Escapologist on Patreon. I’d like to write more essays of substance.

Supermum Retires

Then, a couple of years ago, she retired. Suddenly, her life changed completely. No more 5.15am alarms. Instead, every week it is Zumba and pilates and afternoons at the local cinema with her neighbour and a large glass of red. It is trips to the Tate, the British Film Institute and the Imperial War Museum. It is walks on the beach with new and old friends. It is attending local council meetings to single-handedly overthrow the Conservative party – but always home in time for a bath and Front Row on Radio 4.

Just like that, the grind was over. And now my chest is bursting [with] relief. Now she is not snatching sleep or time or moments with her children. […] Now time ebbs and flows with her command. […] Her once-furrowed brow, anxiously staring into an arsenal of phone screens and pagers and notebooks, now light with smiles when I arrive at her house on a cold, dark evening, and I am the one who is tired, falling asleep on the sofa. Every time she texts me to tell me she is doing the things she didn’t do for 30 years – a Thursday morning yoga class or watching the 6pm news – I remember the tea bags kept in the fridge to cool her tired eyes. And I think: she is not tired any more.

There’s a lot to think about in this daughter’s reflection about her hard-working Civil Servant mother who, in the 1980s, would fall asleep on her feet during bus commutes.

There’s a bit too much to go into here without offering a fully-annotated reprint of the article, so when you read it, do so while thinking about feminism, millennials, boomers, leisure, the work ethic, and the opportunities available if we can only advance our attitudes a little more quickly.