Artefact

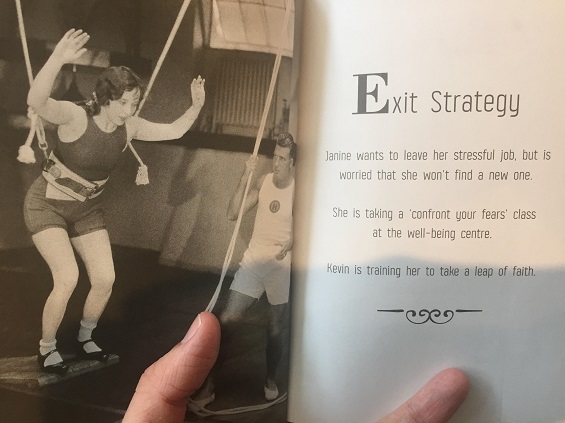

These pages are from one of those “thick greetings card” books. I spotted this one in a shop while out on a walk the other day.

Doesn’t it precisely represent the kind of weak-ass, not-quite-gallows humour found in offices?

As a humorist and Escapologist, here’s what I read in this two-page spread:

Escape is impossible. Creative thought is ridiculous. Metaphor is pretension. The past is lost. Even our own feeble, institutional attempts at improvement — “going on a course” — are futile.

Also note the aesthetically-pukesome hyphenation of “wellbeing” used almost exclusively by management.

Yuck. Happy Monday.

It’s a Shit Business

The reason there are folk on the comedy circuit miserably plodding on, dead behind the eyes, is because they’ve done the same thing for however many years. How can that possibly be creatively stimulating on any level? It’s monotonous toil for a wage, and I’m sure none of us ever started with that goal. It’s a harsh truth that being a jobbing comic will often sap the time and energy that you could spend creating something you really would like to do.

Thinking that stand-up comedy might be your escape from mindless servitude? Think again, says the lovely Ian Boldsworth in a candid essay on his revamped website.

Comics boast to each other that they have no boss, that they are this free spirited, uncensored community who have the luxury of being able to say whatever they want for the catharsis of the masses. The reality has moved away from that. Any jobbing circuit comedian who thinks they don’t have a boss and can say what they want is deluded.

Boldsworth recently quit stand-up in favour of art production, writing, podcasting, and independent film production. Can’t blame him at all. Here’s some info about his film, which (as a Parapod fan) I’m looking forward to seeing. Stop crying.

What Do You Do? Redux

Here are two more escapological nuggets from Miranda Sawyer’s Out of Time, discussed on Friday. (Here’s a link to actually buy the book, since I’m quoting from it so liberally.)

On “What do you do?” Miranda says:

Such an odd thing to ask. What do I do? Lots of things, Nosy. I wasn’t used to the question. Nobody asked that in Manchester, no one asked it in clubs. It was too personal, a bit police-y. If you met someone for the first time, you would just give your first name — if you even said that — and then you’d try to make each other laugh. Comment on the situation you were in, talk music, or dance moves, or maybe football or DJs. Your job never came into it.

This supports my sense of the question’s prevalence being new, a product perhaps of neoliberalsm. Miranda had to go to the bright lights of London to experience it in the 1990s. Today it’s the first thing people ask even here in stinky old Glasgow.

I’ve mentioned this before, but Victorian etiquette expert Emily Post wrote that “what do you do?” is a uniquely boorish thing to say to someone at a social event. Leave work at the door for crying out loud and don’t make people compete with you for status.

Speaking of status:

One of the things I notice now is that in conversations with other people there’s always a status element. It’s disguised but its there. So if someone says they’re so busy they can’t cope, they’re really saying “I’m important because I’m indispensable.” […] Going out to gigs, getting hammered? Still relevant, not old. Know what’s going on locally? In touch with authentic experience. Kids picked for the sports team? Great parenting, plus talent passing down the generations.

This is something I discuss in Escape the Deathly Humblebrag. Let’s smash the work ethic by expunging it from our language!

★ Pleasey-weasy support New Escapologist on Patreon to help keep this blog online and so I can write long-form essays of deep and sexy substance.

Escapology as Crisis

I’m reading Out of Time by Miranda Sawyer. It’s a recent book about midlife crises.

At 34, I’m not quite the intended reader but you never know how long you’ve got left, so the concept of “midlife,” is surely always relevant. Who are you to assume you’ve got a full 83-year lifespan to work with, Mr Complacent-pants? We’re all in a state of mid-life no matter how far along one happens to be. As in “I am amid life.” (Fuck off, that absolutely works).

I’m reading the book because I heard Miranda interviewed on a podcast and I liked her. She strikes me as someone who lives quite fully and won’t have many regrets, but is also aware of mortality and temporariness. That, my friends, is how to live. Her book has been described as “anti-self-help” but it’s really an introspective memoir about youth — as seen from the vantage point of being 45 in 2016 — and time moving on.

As someone who lived through the brilliant, sanguine ’90s and inherited the cultural changes delivered by clubbing, ecstacy, Madchester, Steve Coogan, Britpop and all those magazines but was a bit too young to experience it properly, I’m finding it fascinating. From my perspective, it’s a very-recent-history book, about the ten years that came before my adult consciousness kicked in. Explanations at last!

Anyway, something that struck me are the book’s various descriptions of midlife crisis. Frankly, I think I’ve been in a state of crisis since I was about 11 years old. It’s the sense of there not being enough time to do the things you want to do despite them being relatively modest, the feeling that the odds are against you, and the sense that escape is a solution, and perhaps the only one.

There were other feelings. A sort of mourning. A weighing up, while feeling weighed down. A desire to escape – run away, quick! – that came on strong in the middle of the night.

and:

I would wake at the wrong time, filled with pointless energy, and start ripping up my life from the inside. Planning crazy schemes. I’d be giving [my daughter] her milk at 4am and simultaneously mapping out my escape, mentally choosing the bag I’d take when I left, packing it (socks, laptop, towels), imagining how long I’d last on my savings. I’d be rediscovering the old me, the real one that was somewhere buried beneath the piles of muslin wipes and my failing fortysomething body. I’d be living life gloriously.

So maybe Escapology is the practical application of crisis. This shouldn’t be a surprise. Many people who’ve told me about their sudden, deliberate change in life direction also mention an epiphany — a moment when you’ve got one foot in the commuter train and the other still on the platform and you say “no more” — and what is that but a crisis?

Look at this beauty:

In short, you wake one day and everything is wrong. You thought you would be somewhere else, someone else. It’s as though you went out one warm evening – an evening fizzing with delicious potential – you went out for just one drink… and woke up two days later in a skip. Except you’re not in a skip, you’re in an estate car, on the way to an out-of-town shopping mall to buy a balance bike, a roof rack and some stackable storage boxes. “It’s all a mistake!” you shout. “I shouldn’t be here! This life was meant for someone else! Someone who would like it! Someone who would know what to do!”

I genuinely remember feeling this way when being sent off to secondary school. And again, later, when walking a steep incline one morning to reach a university lecture I didn’t want to attend, to get a degree was ambivalent about, to get a job I’d barely be able to tolerate.

Perhaps a midlife crisis can be experienced at any age, especially to those with strong ideas about the kind of life they want or at least a strong sense of direction that isn’t being granted by inertia alone.

★ Pleeeeeease support New Escapologist on Patreon to help this blog keep going and so I can write long-form essays of deep and sexy substance.