Subscription Essays

Voilà! Here are the subscription essays we’ve published to date.

To unlock the essays, please join us on Patreon.

Season 2 (2019-2020)

Season 1 (2017-2018)

New Essays

About this essay series

The print magazine has drawn to a close but there’s still plenty to say on subjects true to the magazine: work, leisure, minimalism, simplicity, money, culture, and the good life. It would also be nice to cover the operating costs of this very website and the free newsletter. The solution? Occasional, good-value, entertaining essays of substance written exclusively for willing subscribers. Subscribe to a tier that suits you at Patreon.

An Escapologist’s Diary: Part 54. 2018 Review.

Wehey! I have escaped again. How’d you like that, my imaginary shareholders?

Admittedly, this particular escape involved running the clock down on something like a prison sentence more than the commitment to a clever escape plan. But an escape’s an escape and it feels good to be on the lam again, feeling the breeze around the old wosnames.

As some of you know, I put a peg on my nose and took a job when we came back to Scotland from Canada. It was to help my partner secure her visa to live here.

We won that visa in September (using the immense stack of paperwork pictured below) and we immediately set about getting our lives back on course. On my part this means a full-time return to the cheerful, frugal literary life. Much better.

Bagging the visa and escaping office life again were the key events of our 2018, though they do not feel particularly like achievements. It’s just a happy return to the status quo, to what we were doing until someone stopped us.

But hey! there was also the book deal. That was big news. The first half of the advance came in and I started writing. I’ve almost written a whole new book this year. I hope to have finished it by the end of January 2019.

At the start of the year, I set up a mailing list to try and guarantee a readership for my weekly diary. I kept up the diary itself until October (31 entries – medal please) and was rewarded with the highest numbers of visits ever to my website (even if those numbers are admittedly small potatoes). I plan to pick up the diary again in 2019, but not until the book is written, obvs.

There were seven new installments of my Idler column, bringing the total up to 17 (plus extra bits and bobs) and my longest-running gig outside New Escapologist, which hardly counts. I’ve enjoyed getting the occasional email (and Idler letters page response) about the column, none of them (yet) irate.

My stupid face appeared in an art installation (Sven Werner, City Art Centre, Edinburgh) and also in a more domestic setting by my clever wife.

Tim Blanchard’s book about the novelist John Cowper Powys was published in November. I had some small editorial involvement before Tim found a publisher so I was very happy indeed to see the book come out.

For travel, we saw Paris, Malaga, Seville, Gibraltar, and Copenhagen (pictured below in a photograph by AJ).

In non-writerly action I spent the occasional Friday at a botanical library near to where I live. Here I have a freelance project to catalogue the collection. I spend these days handling attractive books about trees and flowers and mushrooms and the likes. Why not?

I also had the pleasure of calling the fire brigade, joining Instagram, remembering the spice girls, finding run-up-to-the-visa solace in the best ever Lego set (and reselling it – minimalism!) and taking a reaction test.

*

As traditional, here is my year in books. A change on previous years is that I’ve stopped recording comic books in this list. There’s too many of them and, let’s face it, it’s a completely different aesthetic experience. (If you’re interested, I enjoyed Ms. Marvel this year and the first volume of The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina. I was surprised not to enjoy the new Multiple Man series.)

I made an effort this year to read some new fiction instead of old everything. I also made my usual effort to read more women and non-white writers.

Lest we forget, an asterisk* denotes an out-loud read while the dagger† denotes a re-read. Schwing!

Bill Bryson – Neither Here nor There

Bill Bryson – The Road to Little Dribbling

Daphne du Maurier – Not After Midnight

Alastair Bonnett – Off the Map

Bill Bryson – African Diary

Joe Dunthorne – The Adulterants

George Orwell – Coming Up for Air †

Shoukei Matsumoto – A Monk’s Guide to a Clean House and Mind

George Orwell – Keep the Aspidistra Flying †

Patrick Hamilton – Hangover Square

Muriel Spark – The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

Sam Selvon – The Lonely Londoners

Donald Westlake – The Hot Rock

Yanis Varoufakis – Talking to my Daughter about the Economy

George Perec – W, or the Memory of Childhood

T. H. White – The Once and Future King

Clive Bell – Old Friends

Darren McGarvey – Poverty Safari

Alex Masters – A Life Discarded: 148 Diaries Found in a Skip

Muriel Spark – The Girls of Slender Means

Helen Russell – The Year of Living Danishly

Caitlin Doughty – From Here to Eternity

Fumio Sasaki – Goodbye Things

George Saunders – Pastoralia

Limmy – That’s Your Lot

Michael Booth – The Almost Nearly Perfect People

Nan Shepherd – The Living Mountain*

Matthew Crawford – The Case for Working With Your Hands

Haruki Murakami – Men Without Women

Matthew De Abaitua – Self and I

Helen Lamb – Three Kinds of Kissing

Kamin Mohammadi – Bella Figura

Tade Thompson – Rosewater

PD James – Sleep No More*

Evelyn Waugh – The Loved One

Jonathan Meades – An Encyclopaedia of Myself

Books read in substantial part but left unfinished:

Richard Sennett – Together: the rituals, pleasures and politics of cooperation

Mary Beard – SPQR

Richard Gordon – Nuts in May

Robert Skidelsky – John Maynard Keynes 1883-1946

I am currently reading After the Snooter by Eddie Campbell (a comic) and Proxies by Brian Blanchfield (essays).

*

I end 2018 happy with my personal lot at the age of 36, though I also feel irritated and under siege for reasons I can’t quite put my finger on. I might have to stop drinking. Or ideally they’ll cancel Brexit.

An Escapologist’s Diary. Part 51. 2017 Review.

Holy Smokes, is that the time? Ja! It’s the (eighth?) annual report to my imaginary shareholders.

Though the world’s terrifying problems continue, 2017 somehow felt like a nicer year than 2016 didn’t it? Maybe it was the encouraging resistance to evil we witnessed around the globe or perhaps it was the incompetence revealed in the devils themselves. Whatever the reason, I certainly feel happier today than I did at the end of 2016. I hope you feel similarly, dear reader.

This being said, much of my year was spent negotiating the aching bullshit of The Hostile Environment. This meant my partner and me working in day jobs again — she full-time, I part-time — and largely putting our frugal, creative lives on hold. But never mind! Things, to some extent, still happened:

In January I wrote a piece about Death and Minimalism for Caitlin Doughty’s blog. It’s only a little thing but CD (as the cool kids call her) and her blog are so phenomenally popular that I still get email about it a year later.

This loudcast also nudged some nice people into my Patreosphere, a funding system that led me to write and post some six new essays (and re-edit six old ones) this year. There will be another dollop of this in 2018, so please join in and encourage a bit more Escapological writing if you can.

In February, my silly face appeared (below) in an Alan Dimmick forty-year retrospective in Edinburgh. It felt good to be welcomed into the Hall of Fame (or Rogues Gallery) that is Alan’s collection of Glasgow hepcats. And look at the essence-capturing greatness of his work — witchcraft, I tell ye.

In May we visited Northern Ireland for the wedding of Escapologists Reggie and Aislinn. It took place in a lighthouse and we were lucky enough to spend a night in this remote (and suspiciously phallic) place.

In the summer, we flew to Montreal for another wedding. It was a beautiful outdoor event and it felt good to be back in Sin City (as nobody ever calls it). There, we lounged in the sunshine, saw Houdini’s handcuffs, and helped install an art show for Andy Curlowe. I say “helped,” but my contribution was largely to eat vegan hotdogs while watching the team hang the paintings. That’s useful, right?

Clubhouse fun with @rubberwringham during setup of Andy Curlowe's show at @GaleriedEste – vernissage ce soir! pic.twitter.com/lE2K3gKUvX

— The Other Samara (@TheOtherSamara) June 7, 2017

On returning to the UK, we popped down to “That London” to record my online course in Escapology with the Idler gang. It was a great treat to drink beer with Tom on the side of the Thames and to pootle about in his Idler world.

In the Idler magazine itself, my column continued through 2017 with another 8 installments, making this my longest-running column.

In August, I crossed the river to see some TV producers in Govan about a possible Channel 4 documentary. I quickly got the sense that the doc wasn’t going to happen, but it was fun to travel to the meeting by boat. I might move to an island — that is, an island smaller than Montreal or, indeed, Britain — just to make this happen.

Back to Belfast in September, this time for cultural tourism. Perhaps the highlight for me was the Royal Ulster Academy Annual Exhibition where we saw this ace crab:

In October, I caught some kid’s helium balloon in my open umbrella. I also teamed up with friends for a Wicker Man ensemble at Halloween.

In November, I got a nice essay into Canadian Notes and Queries, a favourite literary journal. This was a proper bit of writing and I have no idea where I found the time and creative juice to do it. And yet, slightly flirting with Terry Fallis on Twitter was a highlight of my year.

"I didn't win. It went to Terry Fallis, as is traditional." Haha! Issue 100 of @CNandQ containing my piece about the @LeacockMedal came in the post this morning. It is a thing of maximum loveliness. Thank you folks. x @TerryFallis @aaronbushkowsky @CanusHumorous pic.twitter.com/qOUZukHAF2

— Robert Wringham (@rubberwringham) November 14, 2017

In December, Landis and I released a second episode of The Boring Podcast, part of an objects-based collaboration that will, I think, continue next year.

At home, we celebrated Hanukkah in the traditional way — by slightly messing up the mathematically-complicated candle-lighting ceremony. On December 25th we fled the tinselworm and insulated ourselves to Christmas Radiation by walking for an hour to the nearest Odeon to see The Last Jedi.

Throughout the year, our guest room hosted friends from far and wide. There was Emily from New York, Sofia and Drew from British Columbia, Shanti from Montreal, my family from England, Landis from Chicago. When you don’t have the freedom to travel very much, why not bring others to you instead? We also cultivated some new friendships in Glasgow, perhaps especially in Louise, Graeme, and Sven (hi!).

Despite spending a year in the horror of employment, I end 2017 feeling positive and confident. I should be able to pack the day job away in February or March. I suspect I will let you know when that happens, such will be my need to rejoice.

I already know 2018 will be a big year and I’m looking forward to telling you about it as it happens. The escape plan is drafted. The lock picks are primed. Wheels are very much in motion. Bring it on.

*

As is traditional, here is my year in books. It’s a slightly shorter list than usual thanks in part to the aforementioned day job but also in part to a subscription to the eternally-great-but-famously-destructive-to-reading-capacity LRB. Lest we forget, an asterisk* denotes an out-loud read while the dagger† denotes a re-read. Parp!

Patricia Highsmith – The Boy Who Followed Ripley

Robert Sullivan – Rats: A Year with New York’s Most Unwanted Inhabitants

Rutger Bregman – Utopia for Realists

David Nobbs – The Death of Reginald Perrin

Ryan North/Erica Henderson – The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl Vol. 3

Philip Roth – The Ghost Writer

Kakuzo Okakura – The Book of Tea

Simon Barnes – How to be a (bad) birdwatcher

Ann Laird – Hyndland: Edwardian Glasgow Tenement Suburb

Arthur Conan Doyle – The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes*†

Nicholson Baker – How the World Works

Ben Aranovich – The Hanging Tree*

Ernest Hemingway – The Old Man and the Sea

Tom Baker – Who on Earth is Tom Baker?

Nigel Williams – 2 ½ Men in a Boat

Grant Morrison & Darrick Robertson – Happy

J. G. Ballard – Concrete Island

Walter Tevis – The Man Who Fell to Earth

Quentin Bell – Bloomsbury

Quentin Crisp – The Naked Civil Servant

Georges Perec – Species of Spaces and Other Pieces

Patricia Highsmith – Ripley Under Water

Stephen King – Doctor Sleep

Ronnie Scott – Death by Design: The True Story of the Glasgow Necropolis

Janice Galloway – Jellyfish

Roald Dahl – Someone Like You

Penelope Lively – The Purple Swamp Hen and Other Stories

William Golding – The Pyramid

Elaine Dundy – The Dud Avocado*

Amy Licence – Living in Squares, Loving in Triangles

Katherine Mansfield – Bliss and Other Stories

Miranda Sawyer – Out of Time

Dave Simpson – The Fallen

Simon Garfield – The Wrestling

Ben Aaronovitch – The Furthest Station

Piers Anthony – Heaven Cent*

T. E. Lawrence – The Mint

Books read in substantial part but ultimately abandoned (this year, on the unusual grounds of being, simply, shit):

Greg McKeown – Essentialism

Karen Russell – Vampires in the Lemon Grove

Paul Merton – Silent Comedy

Chris Packham – Fingers in the Sparkle Jar

Geoff Dyer – White Sands

As the year closes, I find myself reading Mary Beard’s so-so doorstep SPQR and Richard Sennett‘s soft and bulbous Together.

Being suspicious of sound waves, I never give you a year in music. To make up for this culture dearth, here’s my friend Ian, whose taste is beyond reproach.

Begin With the End in Mind

I’ve never read Stephen Covey’s The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. It looks too long, too managerial, and generally like something Rimmer would read.

Doubtless it’s the sort of book to contain the odd gem or an interesting way of seeing a problem, but this is an effect that leaves me feeling like a gold prospector sifting for nuggets.

(This is precisely how I felt about the famous Getting Things Done when I finally read it last year. In this instance the useful nugget was the word “trusted”).

The 7 Habits was hugely influential and contributed significantly to the tone of modern self-help so it gets mentioned a lot. When it was came up today I found myself wondering what exactly those seven (sorry, “7”) habits are exactly so I looked them up.

Aside from the annoying discovery that I’d independently come up with Covey’s abundance mentality rather belatedly, the best truth nugget lies in the second habit: “Begin with the End in Mind”.

This struck me first as a bit “well, duh” but then it hit me like a suckerpunch.

It had never occurred to me that many people (perhaps even most people?) do not “begin with the end in mind”.

Suddenly, the behavior and decisions of so many people I’ve met over the years made sense. People who binge as soon as pay day rolls around. People who think that checking themselves into wage slavery is a sustainable solution. People who hoard. People who are disorganised. Above all, people who discount the future.

You can probably see how this applies. For example, if someone in receipt of a £1,500 pay cheque had a reasonable, pragmatic, non-punishing idea of how they want their finances to look by the end of the month (e.g. all bills paid, a reasonable amount spent on fun, a minimum of £300 left over for savings) then they wouldn’t start pissing the new income so spectacularly up the wall on Day One.

In the case of being disorganised, I’d sometimes look at a spreadsheet put together by a colleague — multiple sheets scattered across a single workbook, coloured cells, bold text, complicated filters, cells formatted so that phone numbers can’t begin with a “0” — and wonder about the decisions that led to such a mess. I’d think “is this what you wanted your system to look like?” I mean, it didn’t just happen: you clicked on “bold,” you put weird formatting on those cells.

And man oh man, does this apply to minimalism. “Have nothing in your homes that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” is the maxim. Having nothing in one’s home except for the useful and the beautiful is the “end” one must “have in mind”. So when looking at the range of lovely products available to buy, or when given a gift or presented with the opportunity to take something for free, one needs to wonder if it contributes to or detracts from that end.

Some of us probably do this instinctively, but many, I suspect, do not. Covey writes:

It’s incredibly easy to get caught up in an activity trap, in the busy-ness of life, to work harder and harder at climbing the ladder of success only to discover it’s leaning against the wrong wall. It is possible to be busy — very busy — without being very effective. People often find themselves achieving victories that are empty, successes that have come at the expense of things they suddenly realize were far more valuable to them.

It’s sort of bizarre that people fall into this trap so often (or, if we’re being brutal, at all). It’s as though they haven’t worked out that actions have consequences (or that the desirable consequences require specific actions) and instead allow their listing autopilot to drift them into a tempest or throw themselves into performing a host of unhelpful, unrelated actions. Why?

I had an idea a few months ago that I’d quite like to live among a few leafy houseplants so that I might feel a bit more like a monkey in Rousseau painting. What I did next was visit a florist where I acquired a couple of leafy houseplants and I took them home. What I did not do was enlist in a dance class, rub my body down with a prone Cocker Spaniel, or ring up the Natural History Museum to complement them their famous sauropod skeleton. The reason I did not do these things is because they had nothing to do with my envisioned “end” of living among leafy houseplants.

If I found myself performing all of those crazy actions “in pursuit” of fulfilling my house plant ambition, I’d like to think that at some point I’d stop the madness and say “Why am I doing this?”

Which is a good question to ask oneself quite often, really.

Maybe a fault in Escapology is that it assumes people tend to function with an end in mind where, in fact, so many do not.

★ Please, please, please support New Escapologist on Patreon. I’d like to write more essays of substance.

Goodbye Things

We think that the more we have, the happier we will be. We never know what tomorrow might bring, so we collect and save as much as we can. This means we need a lot of money, so we gradually start judging people by how much money they have. You convince yourself that you need to make a lot of money so you don’t miss out on success. And for you to make money, you need everyone else to spend their money. And so it goes.

So I said goodbye to a lot of things, many of which I’d had for years. And yet now I live each day with a happier spirit. I feel more content now than I ever did in the past.

Is another book about minimalism strictly necessary. NO. But never mind. There’s wisdom here and the photos are nice.

Kipple

Watching a 1994 Arena film about Philip K. Dick and — bang — they bring up kipple.

Kipple is a word invented by Dick to describe the sort of detritus that accumulates around you almost without your notice. He means things like half-burned tea lights, light bulbs which may or may not work, and nice pens for which you long ago ran out of ink. They’re there now, haunting the backs of drawers.

In case you’re wondering, this is an ever-so-slightly different sort of clutter to dark matter.

I once started an essay for New Escapologist called War On Kipple in which I’d describe the kipple problem and offer tips on how to keep kipple at bay. I ditched it because there are topics other than minimalsm to write about in Escapology, and even within minimalism kipple is a smaller problem than, say, houses and cars and storage units. It was also too easy to come across as a fascist when talking about the abolition of kipple: does purity matter, ever? Is a maniacal purge of the kipple universe necessary? Maybe there are ways of resolving these questions but this was the line of thinking that made me ditch the essay.

Kipple struck me as an odd thing to include in a documentary about Philip K. Dick in which you’ve only got an hour to play with, so maybe minimalism and entropy have a wider appeal as subjects than I thought.

So if you’re interested in kipple, here’s the discussion about it from Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?:

“Kipple is useless objects, like junk mail or match folders after you use the last match or gum wrappers or yesterday’s homeopape. When nobody’s around, kipple reproduces itself. For instance, if you go to bed leaving any kipple around your apartment, when you wake up the next morning there’s twice as much of it. It always gets more and more.”

“I see.” The girl regarded him uncertainly, not knowing whether to believe him. Not sure if he meant it seriously.

“There’s the First Law of Kipple,” he said. “‘Kipple drives out nonkipple.’ Like Gresham’s law about bad money. And in these apartments there’s been nobody here to fight the kipple.”

“So it has taken over completely,” the girl finished. She nodded. “Now I understand.”

“Your place, here,” he said, “this apartment you’ve picked — it’s too kipple-ized to live in. We can roll the kipple-factor back; we can do like I said, raid the other apts. But — ” He broke off.

“But what?”

Isidore said, “We can’t win.”

“Why not?” […]

“No one can win against kipple,” he said, “except temporarily and maybe in one spot, like in my apartment I’ve sort of created a stasis between the pressure of kipple and nonkipple, for the time being. But eventually I’ll die or go away, and then the kipple will again take over. It’s a universal principle operating throughout the universe; the entire universe is moving toward a final state of total, absolute kippleization.”

★ The post-print phase of New Escapologist is just beginning. Go here to join in.

★ You can also buy all thirteen issues in print or PDF (in newly discounted £20 bargain bundles) at the shop.

An Escapologist’s Diary. Part 48. Artists’ Colony.

We’ve moved again. Such is the life of an Escapologist. Escape is mobility.

You may remember that we returned to Scotland from Canada and, very fortunately, were able to rent a flat quite cheaply from a friend who, making her own great escape, had left her home for pastures new. “Do you want a tenant?” I asked. For over a year we enjoyed a fine Escapological economy, our rent funding a friend’s escape and her property providing us with a hassle- and paperwork-free landing pad.

Well this was always going to be temporary. We wanted a better-situated HQ and our landlady would make more money renting her flat to real people instead of her slacker pals. So two months ago we moved to Hyndland, a part of Glasgow which, Wikipedia boasts, is home to “young bourgeois bohemians including a number of noted authors, poets, actors and footballers.”

I don’t know if I’d describe a footballer as a bourgeois bohemian (I suspect this is the result of two edits, footballers being tacked on by someone, perhaps a Hyndland estate agent, who doesn’t know what is meant by bourgeois bohemia) but you get the idea.

It’s quite posh in a tumble-down, half-reclaimed-by-nature sort of way and our neighbours all seem to be couples who, despite low incomes, won’t tolerate discomfort and ugliness. Suits us.

Almost as soon as we moved in, friend Landis came over from Chicago to live in our spare room for a couple of months. It’s been like having a pet artist. He sits at his drafting table all day long, feverishly cross-hatching and coming out, bleary-eyed, for a snack every full moon or so.

It’s been great having Landis over and our home has felt like a little artists’ colony, with he and Samara drawing and me writing at my laptop and something spicy simmering away on the kitchen stove. Not bad. Every now and then we get together and ad-lib a little project like this podcast about notebooks. We look like this:

When we moved in, all we owned was eight boxes of books and clothes, and three small pieces of furniture: even less than in our last move. The flat was unfurnished, so we had to place orders at Ikea and spend some time mooning around in thrift shops. This is all fairly contrary to my nature, so I’ve tried to see it as a creative venture — making something — rather than simply an acquisitive one.

We’ve been guided by minimalism — Is this thing necessary? How few bookshelves can we get away with? Shall we jettison these? — in an act of what in fact is a considerable expansion to our total mass.

This is a good lesson. Even in acquisition (especially in acquisition) be guided by minimalism. Also, “minimal” is relative to your needs. Just don’t kid yourself about your “needs”.

Having Landis over has been helpful in these early weeks, as he’s been able to help build our flatpacks. In fact, the whole move as been a barn-raising exercise with friends coming over to help with bits and bobs. This is nice not just in that it makes the process easier — many hands, light work — but also in that it imbues a corner of the flat with a memory. The bathroom door is now the door Alan sanded down for us. The futon is the futon Neil helped us to build. The sofa was put together by Peter and Sam. etc.

In other news, the Patreon campaign is going fairly well but perhaps not as well as I’d hoped. I think we’ll be okay but I do need more people on board. Dig deep, if you can, and subscribe to the new essay series for as little as £1.

A funny postcard arrives in the mail this morning from Sam’s parents in Canada, depicting scenes of toque-hatted Montrealers trudging through the grey slush and snowmobiles ploughing through the streets. I am so glad to be in Glasgow right now! But bless you, Canada.

★ The post-print phase of New Escapologist is just beginning. Go here to join in.

★ You can also buy all thirteen issues in print or PDF (in newly discounted £20 bargain bundles) at the shop.

Escape Everything! The Missing Bibliography

A few people said Escape Everything! should have contained a bibliography. I’m sorry it didn’t. This was a bit of an oversight on my part. Since I’d usually name the book or article I was talking about in the main text, I didn’t immediately see a need for a bibliography. But this overlooked the usefulness of having them all in one place and missed the opportunity to talk about books, which is quite unlike me. So here it is: the missing bibliography. It’s thorough but not comprehensive, itemising the widest shoulders I stood on and pointing to further reading. Still, I hope it’s useful and fun. Most of the links go to Worldcat which can help you to find a local library copy. You can buy most of them in the usual places and I recommend Blackwell’s in particular. I’m also happy to discuss these books or provide extra information in the comments thread.

Introduction

The Houdini biography alluded to is The Secret Life of Houdini (2006) by Larry Sloman and William Kalush. Details on Lulu the vanishing pachyderm come from Hiding The Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible (2003) by Jim Steinmeyer. The quote from Adam Phillips comes from his book Houdini’s Box: On the Arts of Escape (2002). For some printed Simon Munnery, I recommend his little volume of aphorisms How to Live (2005) and my own history book about his early work You Are Nothing (2012). Grayson Perry wrote a good book called The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman (2011) and another called Playing to the Gallery (2014). Myles na Gopaleen is the Irish Times pseudonym of Brian O’Nolan (AKA Flann O’Brien), his finest peluche collected in The Best of Myles: A Selection from Cruiskeen Lawn (1968).

Chapter One: Work

Bob Black’s wisdom comes from his essay The Abolition of Work (1985) and is essential reading. The Buckminster Fuller quote comes from an article in New York magazine (1970). David Graeber’s popular essay On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs comes from Strike! Magazine (2013). The “Richard Scarry” quote from Tim Kreider is in The Busy Trap, New York Times (2013) and also inspired a nice cartoon by Tom the Dancing Bug (2014). My history of work material came from many places but one short book I recommend is The Working Life: The Promise and Betrayal of Modern Work (2000) by Joanne B. Ciulla. Notes from Overground by Tiresias is an amazing book, giving the account of an intelligent person’s life in commuter hell.

Chapter Two: Consumption

The idea that your consumption is someone else’s work and the business about a country’s GDP comes from Enlightenment 2.0. (2014) by Joseph Heath and perhaps also his earlier title Filthy Lucre (2009) which delivers in its promise to give “remedial economics for people on the left.” Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered (1973) by E.F. Schumacher is a core text of alternative economics. The prediction of a 15-hour work week comes from Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren (1930) by John Maynard Keynes, but I found it through How Much is Enough?: Money and the Good Life (2012) by Robert and Edward Skidelsky. Bea Johnson’s blog can be found at zerowastehome.com. Enough: breaking free from the world of more (2008) by John Naish is a very inspiring book about living within one’s means. The Music of Chance (1990) is an absurdist novel by Paul Auster and contains all that wonderful stuff about debt, labour and thankless wall-building.

Chapter Three: Bureaucracy

The detail about “International Business Machines” comes from IBM and the Holocaust (2001) by Edwin Black. Green MP Caroline Lucas’ book is called Honourable Friends?: Parliament and the Fight for Change (2015) and is marvellous and must be read before parliament is reformed and it goes out of date!

Chapter 4: Our Stupid, Stupid Brains

The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) and Coming Up for Air (1939) by George Orwell are both essential reading for free thinkers; the former being a collection of journalism on working-class life, and the latter an absorbing novel about nostalgia and the present. Sartre’s idea of Bad Faith is articulated in Being and Nothingness (1943), which is barely readable and best avoided, perhaps in favour of his novel Nausea (1938). Roald Dahl discusses his life as a Royal Dutch Shell employee in his memoir Going Solo (1986). Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art is that neat little book about Resistance. David Cain’s wise essays can be read for free at Raptitude.com. Brian Dean’s great website lives at anxietyculture.com and he also wrote a nice article, “Escape Anxiety,” in New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009). Alain de Botton’s Status Anxiety (2004) is essential stuff, especially the “thesis” page and the Bohemia chapter. Mark Fisher’s essay is called “Suffering with a Smile” and appeared in The Occupied Times (2013). Tom Hodgkinson’s How to be Free (2006) is the most essential reading of all and his How To Be Idle (2004) and Brave Old World (2011) are good too. Musings on the prisoner’s dilemma comes from Andrew Potter and Joseph Heath’s The Rebel Sell (2004).

Chapter 5: The Good Life

The Kama Sutra is an ancient Indian text on the good life, a goodly portion of which is dedicated to rutting. Lin Yutang is the writer of, among other works, The Importance of Living (1937), which is highly readable and worth your time. Much has been written on Eudaimonia and the core texts are probably Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Eudemian Ethics. The stuff about consumers versus appreciators comes from Happiness: A Very Short Introduction by Daniel M. Haybron (2014). Palliative nurse Bronnie Ware’s Regrets of the Dying is a blog post from 2009. For more on Epicurus I refer you again to Status Anxiety (2004) by Alain de Botton. For more on the Stoics try A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy (2009) by William B. Irvine. I make brief reference in this chapter to The Urban Bestiary: Encountering the Everyday Wild (2009) by Lyanda Lynn Haupt, The Cloudspotter’s Guide (2006) by Gavin Pretor-Pinney, both of which are worth a look, and Look Up Glasgow (2013) by Adrian Searle. For books to get you excited about astronomy, you can’t go wrong with Cosmos (1980) by Carl Sagan or some of the amateur astronomy introductions by Patrick Moore. I make passing reference to The Fruit Hunters (2008) by Adam Gollner. “The last piece of chocolate in the universe” is the idea of my child self but something similar apparently appears in Savor (2015) by Niequist Shauna. I make an incorrect claim that the 10,000 rule comes from Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point (2000) when in fact it comes from the same author’s Outliers (2008).

Chapter 6: How Escapologists Use Their Freedom

The crab anecdote comes from an extremely charming work of naturalism and neurology called The Soul of an Octopus (2015) by Sy Montgomery. The quote about Wall Street and toilet cleaning comes from Vagabonding (2002) by Rolf Potts, which is worth reading if you ignore the garbage about working for one’s happiness. The Oscar Wilde quote about “the perfection of the soul within” comes from his essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism (1891). Tom Hodgkinson’s New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009). The concept of “Filling the Void” is well-trodden territory but that phrasing of the problem comes from The 4-Hour Work Week (2007) by Tim Ferriss. The Voyage of the Beagle (1839) is Charles Darwin’s account of his five-year voyage around the world and is surprisingly readable for its age and highly likable.

Chapter 7: A Montreal Year

“That Will Do” is what Houdini said to the McGill University student who punched him repeatedly in the stomach just before he died, a fact that comes from the Houdini biography referenced in the introduction section above. Much wisdom can be found in A Philosophy of Walking (2014) by Frédéric Gros as well as The Lost Art of Walking (2008) by Geoff Nicholson. For approachable natural history, try anything by Gerald Durrell, Leonard Dubkin ad Lyanda Lynn Haupt. Passing reference is made to Robinson Crusoe (1719) by Daniel Defoe and I’d also recommend a novel about it’s author Foe (1986) by J. M. Coetzee. If you’re interested in eating your way to immortality, Fantastic Voyage (2004) by Ray Kurzweil and Terry Grossman is the go-to text albeit a little old.

Chapter 8: Preparation

The quotation from Charles Simic (not Simi – a typo I had nothing to do with) comes from The Monster Loves His Labyrinth: Notebooks (2008). “I never hear the word ‘escape'” is a poem by Emily Dickinson and can be found, strangely enough, in The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. The details about Robert Graves’ assertion that there’s no money in poetry comes from Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900-1939 (2002) by Virginia Nicholson which is essential to read if you’re interested in Bohemian life, though I also refer briefly to his memoir Goodbye to All That (1929). An account of Alexander Supertramp’s life can be found in Into the Wild (1997) by Jon Krakauer. Dandelion Wine (1957) is a lovely if a tad bucolic novel by Ray Bradbury, a quote from which appears in New Escapologist Issue 1. The cancer diaries referred to belong to the library of a hospice I worked in.

Chapter 9: Escape Work

Arbeit macht frei means “work sets you free” and appears in the ironwork gates at the Auschwitz work/death camp, a fact I first learned from If This Is a Man (1947) by Primo Levi. Jacob Lund Fisker’s book is called Early Retirement Extreme (2010) and evolved from his blog of the same name. I make passing reference to an item from The Onion (2015) and another, The Strange and Curious Tale of the Last True Hermit, from GQ magazine (2014). Rob West’s blog charting the progress of his house-building project in British Columbia is called The Hand-Crafted Life. Ben Law’s core work on traditional house-building techniques is called Woodland Craft (2015) and Mark Boyle’s “Moneyless Man” column (2009-10) is archived at the Guardian website. Nicolette Stewart’s item about tiny homes can be found in New Escapologist Issue 8. Walden: Or, Life in the Woods (1854) by Henry David Thoreau is the obvious starting point for anyone considering a life in the woods near their mum’s house. Montreal Martin’s blog is called Things I Find in the Garbage. The interview with Michael Palin referred to is in Idler 37 (2006); I’m in it too, albeit under the wrong name, with a cover story called “Death to Professionalism”. How to Avoid Work (1949) by William J. Reilly is a witty and tricky-to-find-in-shops postwar career manual. Wringham’s escape plan first appeared in New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009).

Chapter 10: Escape Consumption

Mr Money Mustache has a blog of that very name. Diogenes of Sinope can be encountered in Diogenes of Sinope – The Man in the Tub (2013). Some of the practicalities of minimalism were first printed in New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009). Joshua Glenn’s The Wage Slave’s Glossary (2011) is an electric little book and is in fact a sequel to his The Idler’s Glossary (2008).

Chapter 11: Escape Bureaucracy

Roderick Long’s “delusional street person” comes from Just Ignore Them (2004) in Strike at the Root. La Boétie wrote Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (1576) which I came across in the dazzling How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in one question and twenty attempts at an answer (2010) by Sarah Bakewell. Kafka’s The Trial (1925) is the go-to work of fiction for bureaucratic absurdity. Narnia and Bas-Lag are the worlds of C. S. Lewis and China Mieville respectively. I don’t recall where I read about Chiune Sugihara but there’s a nice item about him in the Japan Times (2015). The Pomodoro Technique (2006) is a cute but effective productivity system concocted by Francesco Cirillo.

Chapter 12: Escape from our Stupid, Stupid Brains

Naked Stephen Gough’s point about being good comes from a Guardian (2012) item. The stuff about fear of flying versus rationalism comes from Risk: The Science and Politics of Fear (2008) Dan Gardener. The mags I recommend for longform journalism are The New Yorker, Jacobin and Aeon. Much of my info on the Bohemians of history is from Among the Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900-1939 (2003) by Virginia Nicholson. Caitlin Doughty is mentioned, whose first book is Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematorium (2014). The Wise Space Baby was originally mentioned in New Escapologist Issue 10 (2014), and the “damning conclusions” drawn by astronauts on the international space station are alluded to in An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth (2013) by Chris Hadfield. The Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale (1967) is a real thing and can be seen on Wikipedia. The stuff about Quat leaves comes from The Devil’s Cup: A History of the World According to Coffee (1999) by Stewart Lee Allen.

Chapter 13: The Post-Escape Life

Henry Miller’s list can be seen in Henry Miller on Writing (1964).

Epigrams

“Love laughs at locksmiths,” comes from a signed photograph of Houdini but has an older origin, featuring on an 1805 satirical print held by the British Museum. The other Houdini epigrams come from Handcuff Secrets (1907), Magical Rope Ties And Escapes (1920), Miracle Mongers and Their Methods (1920), Houdini’s Paper Magic: The Whole Art of Performing with Paper (1922).

★ Escape Everything! by Robert Wringham is available in libraries and was commercially re-released in paperback as I’m Out: How to Make an Exit.

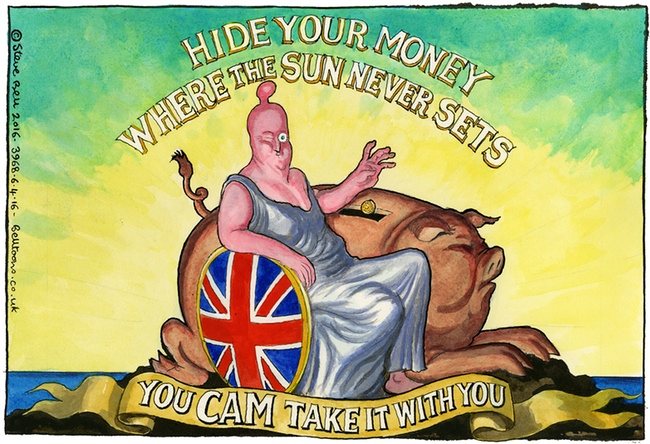

How to Avoid Tax Properly

In the wake of the Panama Papers I’d like to offer some advice to The Elite.

There are far easier ways to avoid paying tax than what you lot get up to. Why trouble yourself and sully your reputation over complicated offshore affairs when you could simply work less?

I join the nation in calling for the Prime Minister’s resignation, but unlike the nation I have the PM’s best interests at heart.

In the UK, as a politician of all people should know, you can earn as much as £11,000 before you’re asked to pay anything to the tax office. That’s plenty to live on, so stop earning, silly. Millions of people earn far less without the motivation of tax avoidance!

Bertrand Russell observed this long ago: “In view of the fact that the bulk of the public expenditure of most civilized Governments consists in payment for past wars or preparation for future wars, the man who lends his money to a Government is in the same position as the bad men in Shakespeare who hire murderers. The net result of the man’s economical habits is to increase the armed forces of the State to which he lends his savings. Obviously it would be better if he spent the money, even if he spent it in drink or gambling.”

Unfortunately, if you’re serious about this, there’s also consumption tax (that’s VAT here in the UK) to avoid. This means ceasing to buy so much stuff. This is called minimalism or voluntary simplicity. Historically, it’s been seen as a highly virtuous way to live.

You can still do your civic duty by paying at least some consumption tax–perhaps on groceries and other noshable goods–and by paying your council or municipal tax. I love to pay my council tax because it funds the things I like and things that benefit the community instead of the central government and those armed forces and bombs. £140 a month (between two!) for clean water, sewage removal, garbage and litter collection, schools, libraries and parks is a bargain. Moreover, when you work less you’ll really get the most out of those things.

My advice to the tax-dodging rich is to get real and do it properly with your reputation intact. Stop working. Nobody will miss you. Retire with dignity to a nice cottage with a view somewhere and write your memoirs. Quietly. Maybe your book could be called How I learned to stop swindling the nation and love to loaf.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

Doublespeak

George Monbiot today on the inherent problem of consumerism and economic growth.

Governments urge us both to consume more and to conserve more. We must extract more fossil fuel from the ground, but burn less of it. We should reduce, reuse and recycle the stuff that enters our homes, and at the same time increase, discard and replace it. How else can the consumer economy grow? We should eat less meat to protect the living planet, and eat more meat to boost the farming industry. These policies are irreconcilable. The new analyses suggest that economic growth is the problem, regardless of whether the word sustainable is bolted to the front of it.

It’s not just that we don’t address this contradiction; scarcely anyone dares even name it. It’s as if the issue is too big, too frightening to contemplate. We seem unable to face the fact that our utopia is also our dystopia; that production appears to be indistinguishable from destruction.

It’s a tricky article if you’re not into economics and you might have to hold tight through the explanation of “decoupling” but it really is worth it if you want to think further about the social value of Escapological traits like minimalism and quitting your job.

★ Buy the latest print issue of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or pre-order the book.