50 Hoped-For Escapes

I once mentioned a website called 43things. It doesn’t exist any more but I wrote a note of something I found there. (Update: the site is back!)

43things was a social network about personal ambitions. You’d enter your dreams and goals and other people could cheer you on. When successful, you could write a little post about how you did it and whether it was worth it.

I mainly used it to eavesdrop on other people’s life plans.

I once popped the word ‘escape’ into the in-site search engine and came up with some 472 items. The result was like a measure of gross international unhappiness. Or at least dissatisfaction. Or, more positively, a measure of people’s desire to put things right in their lives.

Many of the ‘escape’ ambitions are either similar to other ones or don’t make sense, so I’ve boiled them down to a single report of 65 hopes for escape. It’s almost like a poem, composed by the Citizens of the Internet, circa 2013:

Escape the masses

Escape from Google

Escape into nowhere

Escape my past

Escape from this city/country

Escape the cubicle

Escape America

Escape from Alcatraz

escape death

escape reality

escape society

escape capitalism

Escape my parents

Escape From Jail

Escape materialism

escape Suburbia

escape from it all

Escape escapism

Escape…(for a while)

escape from myself

escape to a rainforest

Escape solitude

Escape from Zajecar for a while

escape from my life

escape winter

escape poverty

escape by train

Escape Debt

escape depression

Escape England!

escape the office

escape the routine

escape the midwest

escape the “curse”

escape from my ego

escape Nottingham

escape to paradise

escape plastic

Escape from Shawshank

Escape religion

Escape Ireland!

Escape from Iran

escape from LA

escape tradition

escape everything

escape from intolerance

Escape anxiety

escape from the matrix

escape to scotland

escape a life of corporate servitude

Pssh, I could tell you how to do any one of those.

The Mysticism of Work

Found in a zine by Amy Peltz, a quotation from Simone Weil:

Why has there never been a mystic, peasant or worker to write on the use to be made of disgust for work? Our souls fly from this disgust and try to hide it from themselves by reacting vegetatively. There is a mortal danger in admitting it to ourselves. This is the source of the falsehood peculiar to the working classes.

There has now, Ms Weil. It’s New Escapologist!

Of Design and Destiny

Must modern cities be ugly? Of course not, and they are not. But I walk past this “Skypark” thing quite often and it’s horrible. I mean, look at it.

It stores a few hundred teleworkers between 8am and 8pm, which is an act of evil in itself, but must it look like one? I’m only a passerby — I don’t deserve to be insulted.

“Know your place,” that building says, “You’re a cog in a machine in a grey, grey world.”

I like to wear a colourful pocket square when I know I’m due to pass it. It’s on a street corner with a lot of traffic, so I sometimes play with my yo-yo while waiting to cross.

“Such frivolousness,” the building says, “Earn your pittance! The grave is your destiny, so get trudging!”

Everyone likes the idea of beauty but we’re increaingly turning our backs on it because of some vague notion about the importance of professionalism and seriousness. To be beautiful is to be eccentric or profligate.

Design today must apparently be hard-edged, sober, practical, sturdy, and — while actually very expensive — look cheap. That, or it can be beautiful and temporary and safely stashed in a museum where nobody will see it.

To add a little flourish or some colour or nuance — or even to spell something properly — is seen as increasingly anachronistic.

I’m always cheered to see a red telephone kiosk. It’s a design classic, it works, it’s an internationally-adored symbol of Britain. It’s cheap to use, it’s practically indestructible, and it can be trusted to deliver. Most of us would love to have one on our street corner, but we can’t apparently.

BT started getting rid of the red telephone box in about 1985, planting those horrible black perspex ones instead. You just know this was the result of a meeting in which some influential philistine said “the classic red telephone box does not reflect BT’s corporate values.”

The new kiosks said everything about municipal mediocrity. “Don’t go thinking you’re part of an empire,” it said, “don’t go thinking you’ve got better things to do than go to school and get a job and die.”

I mean, look at that one in the middle. They were routinely vadalised but how could they not be? I’d love to smash that one in. It’s practically what they’re for. In response to this public disdain and an outspoken nostalgia for the classic red box, BT brought out a happy medium which looked a bit like the shitty modern ones but with a domed top reminiscent of the classic.

The message was “Yes, everyone likes the classic… but we can’t have it because of the way the world is going. Nobody likes the modern version, but we have to have it this way. Haven’t you heard of inevitable decline? You have to work pretty hard to fulfill a thing like that.”

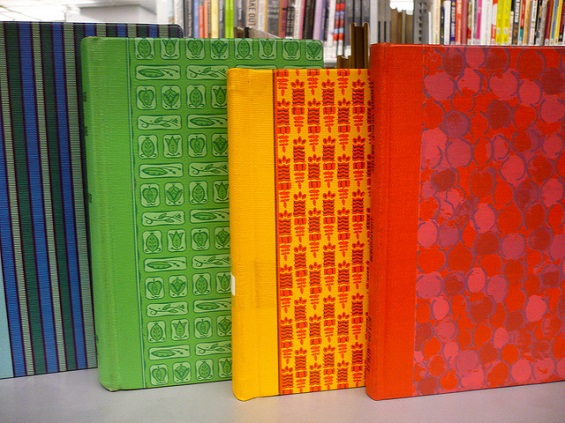

I once visited the Central Public Library in Seattle — a great building designed by Rem Koolhaas — and saw many beautifully-bound books inside. A one-time librarian, I knew the story of these books just by looking at them. The library once had its own bindery in which many old books were carefully rebound to extend their lives. Beautiful materials were chosen to bind the books so they’d be pleasing to the eye. The bindery was closed circa 2002 “because that’s not how things are done today”.

The present day is about Kobo and iPads, not beautiful, free-to-borrow books no matter how much we like the idea and how much sense it makes. Imagine a world in which people carried these books around the city instead of e-readers. It would be beautiful but we can’t have it because of an imaginary landscape called “the way the world is now.”

It’s a destructive logic causing good ideas to be stifled at birth or else scrapped after decades of flawless service. All because of cultural pessimism. It’s as if our national and international misery is seeping upwards into our design.

The implication is that we live in a time of austerity, utility, uniformity, corporate values, plasticity, disposability. Our period cannot be allowed to be one of domesticity, prettiness, happiness, dignity, peace, quiet or luxury.

The idea is that everything is doomed. It suggests there’s no alternative, that ugliness is inevitable, and that the destiny of all material — including human brainstuff — is to contribute to this harsh and sober vision.

But it’s not destiny. It’s all unnecessary. Britain and America are among the richest countries in the world. We’re producing more artists and designers than ever before. The world doesn’t need to be about the bottom line. Bladerunner was a warning, not a blueprint, yet look at the state of the London skyline: symbolic of little but graceless corporate guzzling. “Skypark,” meanwhile, sounds like something from Terminator 2: Judgement Day, a world where robots are in charge and love is on the scrap heap.

It doesn’t have to be this way, my pretties. Design your own lives. Act, move, earn, and speak beautifully. The others will join in sooner or later. Act as if you lived in the early days of a more beautiful world.