Merlyn, Badger, Ants.

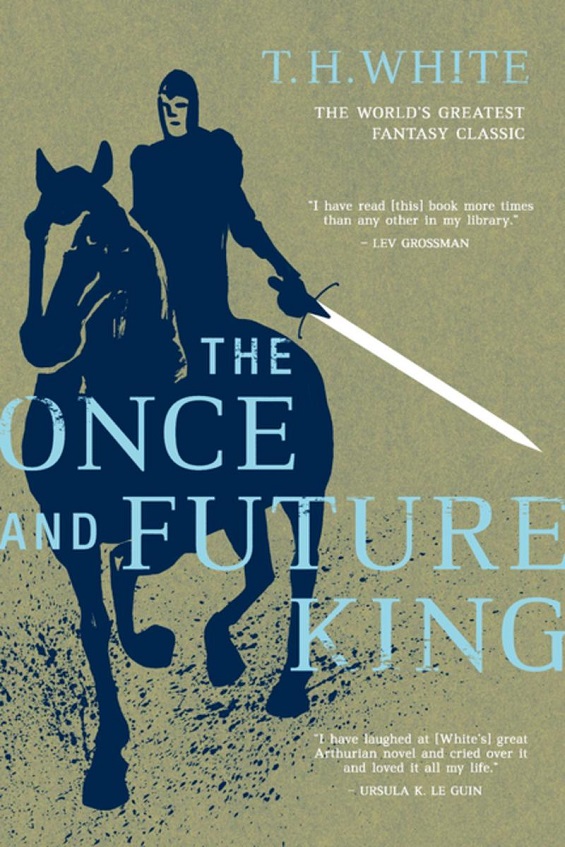

People seemed to enjoy the extended quote about pigeons taken from T. H. White’s The Once and Future King, so here are three other tidbits I marked in my copy with little sticky notelets.

The Once and Future King is actually four books in one volume, the first of which, The Sword in the Stone is the most famous and concerns young Arthur’s education by Merlyn.

“The best thing for being sad,” replied Merlyn, beginning to puff and blow, “is to learn something. That is the only thing that never fails. You may grow old and trembling in your anatomies, you may lie awake at night listening to the disorder of your veins, you may miss your only love, you may see the world about you devastated by evil lunatics, or know your honor trampled in the sewers of baser minds. There is only one thing for it then — to learn. Learn why the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing that the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting. Learning is the thing for you.”

Arthur’s education often takes the form (as with the pigeon) of animal metaphor and fable. This, I think, is down to T. H. White and his introvert’s love of natural history. Usually, the fables are experienced up close ad personal with the animals when Arthur is routinely transformed by magic into one of their number and sent to visit their societies.

“So Merlyn sent you to me,” said the badger, “to finish your education. Well, I can teach you only two things — to dig and love your home. These are the true end of philosophy.”

The badger is right. The point of philosophy is to live well and a love for your “home” (one’s house, but also society and one’s own mind) is both the result of living well and the means. Digging, to me, refers to a life spent investigating, experimenting, quiet husbandry, maintenance, learning, and not infringing.

My favourite chapter so far (or at least the chapter I’ve found most remarkable) is one in which Merlyn transforms the boy into an ant and sends him into an ant nest. It’s a strange chapter and stands apart from the rest of the book. It feels just like an H.G. Wells or Jules Verne story in both tone and the depth of imagination.

The ants have a work-orientated society and White does not find this admirable. The ants see everything through the lens of productivity, describing everything as either “done” or “not done,” the former being inherently good and the latter inherently bad. A delicious morsel is considered “done” and the same morsel, if found to be contaminated with poison, is “not done.” They see everything in these binary terms, their lives an unending sense of getting things “done”.

There’s a nice satire of the “what do you do?” question versus the Escapologist:

“What are you doing?” The boy answered truthfully: “I am not doing anything.” [The ant] was baffled by this for several seconds, as you would be if Einstein had told you his latest ideas about space. Then it extended the twelve joints of its aerial and spoke past him into the blue. It said: “105978/UDC reporting from square five. There is an insane ant on square five. Over to you.”

About Robert Wringham

Robert Wringham is the editor of New Escapologist. He also writes books and articles. Read more at wringham.co.uk