Perruque

Here’s a fun word I haven’t come across before: perruque. It means to pilfer time or surplus resources from work.

It’s not in either of Glenn’s Glossaries, which is probably forgivable since I found it in an essay called “18 Semiconnected Thoughts on Michel de Certeau, On Kawara, Fly Fishing, and Various Other Things,” which some might say is off the beaten track.

It comes up when the essayist, Tom McCarthy, is talking about Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life, a 1974 book about the ways in which people personalise or adapt what the built environment gives them. (To give you a better idea of what this means, the cover usually shows an image of desire lines).

McCarthy writes:

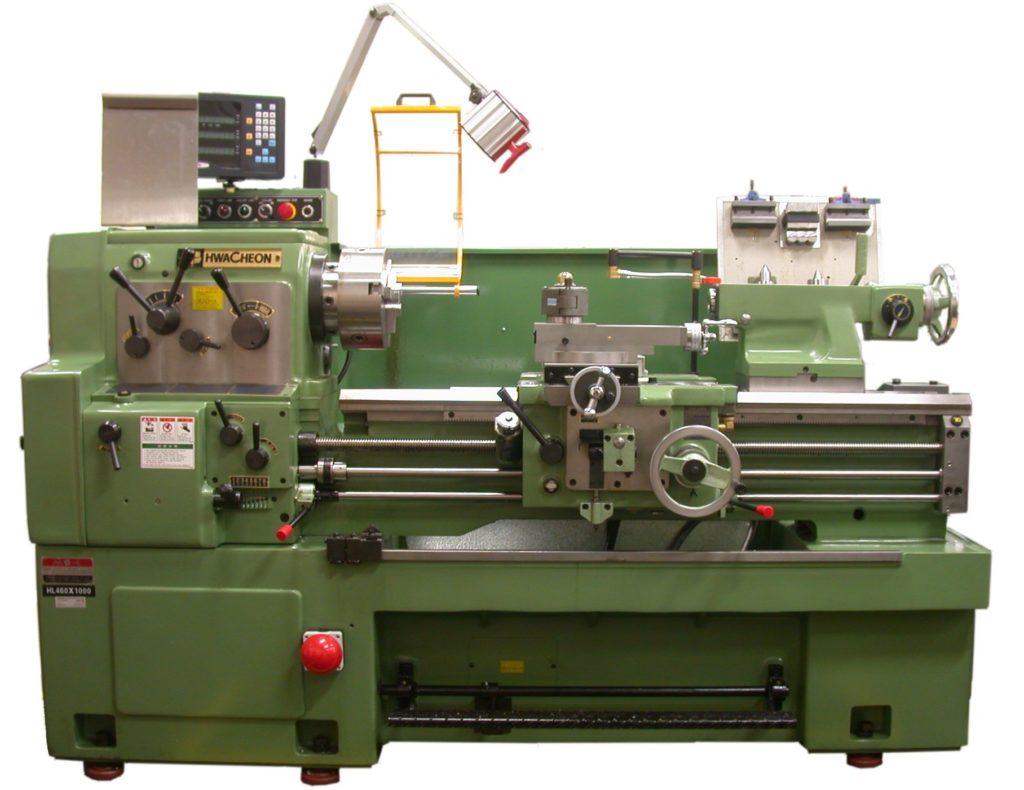

Perruque is when the little guy, the worker, does something for his own ends under the guise of obediently serving his employer. When a cabinet maker uses a lathe to make a piece of furniture for his living room, that’s perruque; so is when a market researcher or ad agency employee abandons himself to reverie for half an hour. Whacking off on the boss’s time.

I mention this excitedly to my wife who says perruque is the French for “wig.” What would that have to do with this? I ask, meaning etymologically. “Subterfuge,” she says.

(We laugh because of a moment we remember in Samuel Pepys’ Diary in which Pepys, noticing a fashion for powdered wigs, has a wig made of his own hair and passes it off as real for his own amusement; as well as being delightfully puerile and containing the idea of Pepys being blissfully unaware of everyone around him saying “hark at Sam wearing a wig of his own hair,” he has spectacularly missed the point that wig-wearing was supposed to be conspicuous).

Samara, ever brilliant, owns a copy of The Practice of Everyday Life so we pluck it from the shelf and find she earmarked the page about perruque years ago.

The example of the cabinet maker is right here in de Certeau (a bit lazy, McCarthy). He also provides the lovelier example of “a secretary’s writing a love letter on company time.”

He continues:

Accused of stealing or turning material to his own ends and using the machines for his own profit, the worker who indulges in la perruque actually diverts time (not goods, since he uses only scraps) from the factory for work that is free, creative, and precisely not directed toward profit. In the very place where the machine he must serve reigns supreme, he cunningly takes pleasure in finding a way to create gratuitous pro-ducts whose sole purpose is to signify his own capabilities through his work and to confirm his solidarity with other workers or his family through spending his time in this way. With the complicity of other workers (who thus defeat the competition the factory tries to instil among them), he succeeds in “putting one over” on the established order on its home ground.

A very fine example of sticking it to The Man. It’s also an example of what I once described as “escaping the Holodeck using holographic tools.” You mustn’t feel bad about perruch. You owe your escape to the greater good and it’s no fault of yours if the captor has left some handy holographic shovels and power drills lying around.

New Escapologist was originally a perruch project of sorts: blog entries pecked out on company time and a pilot issue printed on A4 stolen from temp jobs (as apparently was Processed World, another magazine about office confinement).

*

Issue 14 of New Escapologist is available from our online shop.

About Robert Wringham

Robert Wringham is the editor of New Escapologist. He also writes books and articles. Read more at wringham.co.uk