A Burning Desire for the Open Air

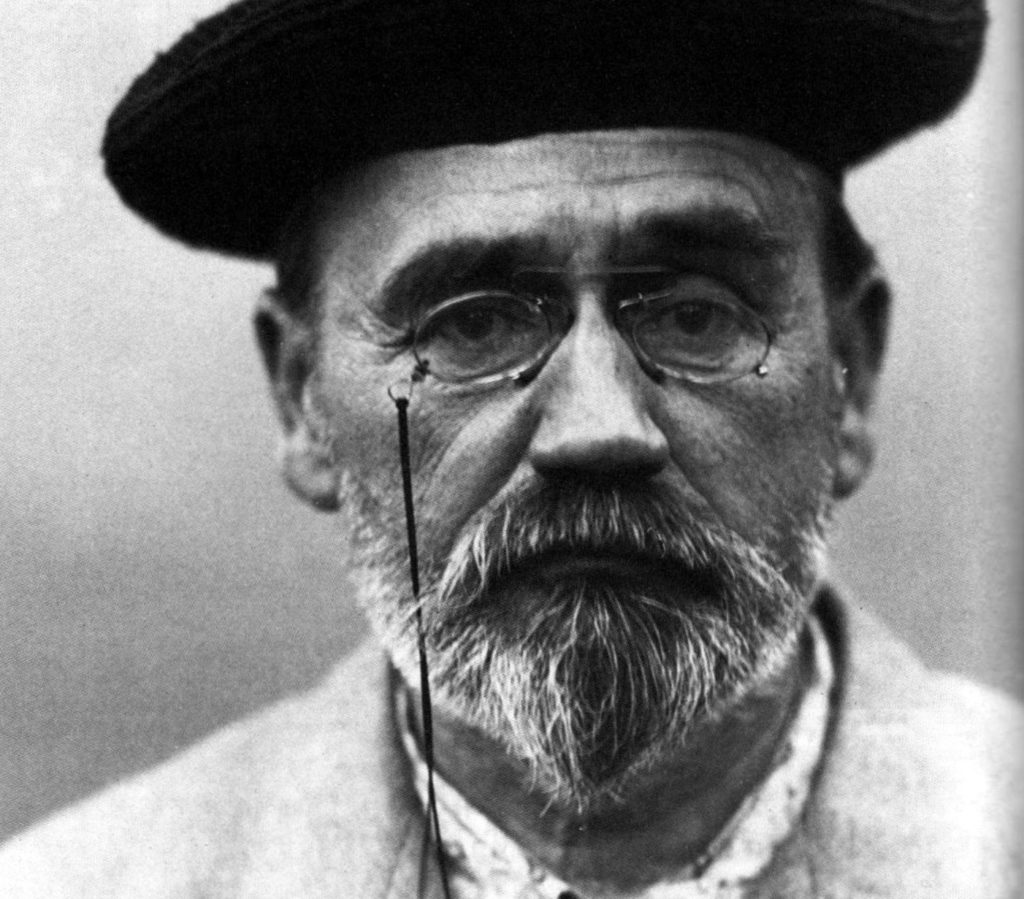

Émile Zola didn’t take any prisoners when describing the lower middle classes in 1868. I’m reading his novel Thérèse Raquin:

Thérèse, who finds herself living in stultifying domestic mediocrity, longs for freedom:

They brought me up, they received me, and shielded me from misery. But I should have preferred abandonment to their hospitality. I had a burning desire for the open air. When quite young, my dream was to rove barefooted along the dusty roads, holding out my hand for charity, living like a gipsy.

and

You will hardly credit how bad they have made me. They have turned me into a liar and a hypocrite. They have stifled me with their middle-class gentleness, and I can hardly understand how it is that there is still blood in my veins. I have lowered my eyes, and given myself a mournful, idiotic face like theirs. I have led their deathlike life. When you saw me I looked like a blockhead, did I not? I was grave, overwhelmed, brutalised. I no longer had any hope. I thought of flinging myself into the Seine.

This reminds me of a film I saw recently called His House. It’s a horror film about Sudanese refugees who must start a new life in the English Midlands. Of the low-level English pen-pushing bullies they encounter, they say:

They don’t want to be reminded that it is them that are weak. How poor and lazy and bored they are.

It’s not only homelife Zola despises. He really takes aim at the office. People who want to work in offices, represented by Thérèse’s meek husband Camille, are idiots and try-hards. Her secret lover Laurent meanwhile, a more creative fellow albeit not a successful one, must also work in an office but against his will:

With stomach full, and face refreshed, he recovered his thick-headed tranquillity. He reached his office and passed the whole day yawning and awaiting the time to leave. He was a mere clerk like the others, stupid and weary, without an idea in his head, save that of sending in his resignation and taking a studio. He dreamed vaguely of a new existence of idleness, and this sufficed to occupy him until evening.

In Zola’s world, some people (like Camille) are idiotically seduced into The Trap by empty promises of status. Others are pushed into it by circumstance: through financial desperation or through their failure to do something better. Loverboy Laurent isn’t a very good portrait painter but, when left to his own devices later in the book, he starts to thrive. Time and space are what he needs but the system denies them to him.

Laurent’s failure to live up to his real calling and Thérèse’s deep domestic boredom lead them on a chaotic path of adultery and murder. They become a social problem. The system fails individuals, obviously, but in doing so, fails us all.

*

About Robert Wringham

Robert Wringham is the editor of New Escapologist. He also writes books and articles. Read more at wringham.co.uk