Naughty, Idle, Ungodly

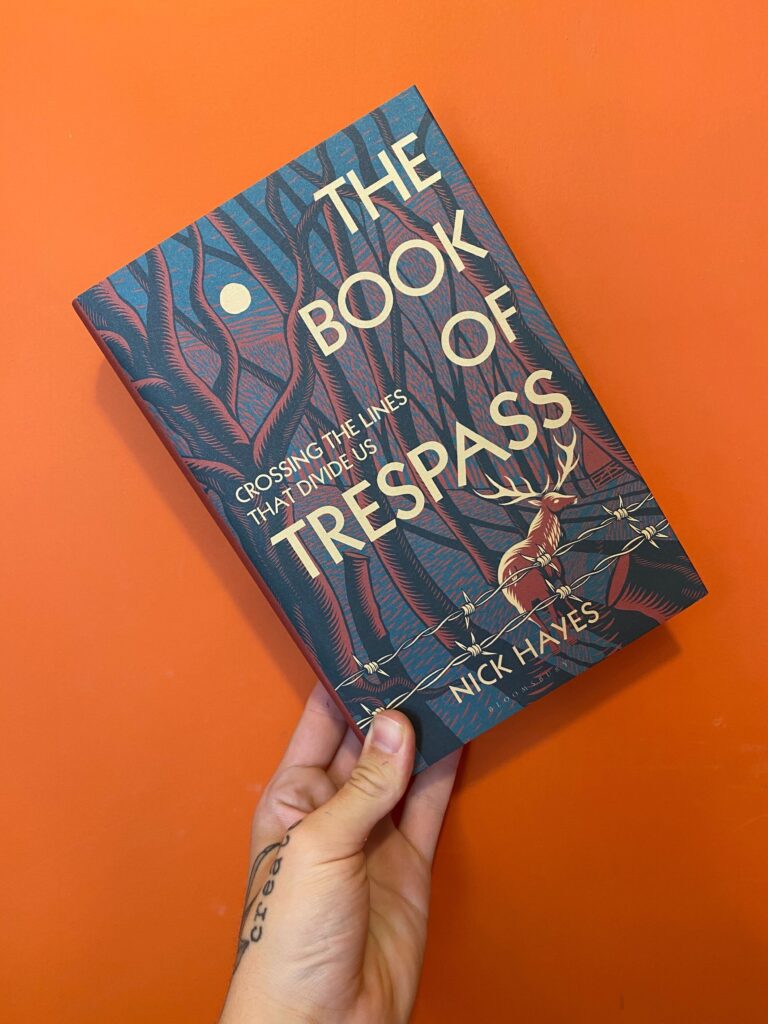

The Book of Trespass by Nick Hayes (who was a very early contributor to New Escapologist, fact fans) is brilliant. It’s well researched and far wider reaching in its politics than I had imagined.

In my bones I like the idea of trespass — of sticking it to impossibly wealthy gods of the establishment with little more than fleet-of-foot mischief — but the book goes intelligently into the intersections of racism, feminism, slavery and many other topics, underpinned as they are by exclusion and enclosure and may one day be brought to heel by a mass movement in land justice. As well as telling unapologetically magical stories of walks in the countryside, Hayes makes painstaking research dives into law and statute. It’s a remarkable book.

The crossover of trespass and escape is probably obvious — we aspire to wander — and we’ve covered the arts of trespass in the magazine, perhaps most prominently in Issue 12. But look at this majesty from Hayes’ chapter on gypsies and vagabonds:

In 1388, the Statute of Cambridge placed […] restrictions on the movement of people […] The law applied to a broad church of people: itinerant labourers, tinkers, pedlars, unlicenced healers, craftsmen, entertainers, prostitutes, soldiers and mariners. They were freelancers whose jobs did not require them to be tethered to one place or another. They were called ‘masterless men,’ and they roamed as lone wolves or packs of wild dogs, haunting the countryside, towns and minds of their betters. […] Vagrancy was vague — it sought to criminalise not antisocial behviour, but rather a state of being, a social and economic status, a type of person.

Then, under an Act of law set by Queen Mary in 1554, Gypsies and vagabonds would be hanged.

However, in a detail that expresses the real root of the fear, the legislation allowed them to escape prosecution as long as they abandoned their nomadic lifestyle or, as the Act put it, their “naughty, idle and ungodly life and company.” It was not their race, origin or palm reading that upset the state, it was their mobility.

concluding that:

Fixity is the orthodoxy of the modern European age […] Property simply cannot comprehend mobility.

Couldn’t have put it better myself.

I’ll probably have more to say about the book as I progress, but there’s clearly so much of value and interest to Escapologists in The Book of Trespass that you might as well just get it. It’s abundant in libraries or can be bought practically anywhere.

*

About Robert Wringham

Robert Wringham is the editor of New Escapologist. He also writes books and articles. Read more at wringham.co.uk