Our Plain Duty to Escape

A reader called Robin as us to consider this Ursula K. Leguin quote:

Fantasy is escapist, and that is its glory. If a soldier is imprisoned by the enemy, don’t we consider it his duty to escape? … if we value the freedom of the mind and soul, if we’re partisans of liberty, then it’s our plain duty to escape, and to take as many people with us as we can.

Right. This is why we, at New Escapologist, have come to separate “escapism” and “Escapology”:

It’s Escapology, not escapism. Escapism is when you briefly leave your cares behind by watching a film or building model aeroplanes. Escapology is a permanent effort to leave work and consumerism behind. It’s the art and science of politely saying “no thank you,” and walking away into a self-made alternative.

We’re not the only one to make the distinction. Escape, Escapism, Escapology by John Limon is a recent book that does the same. We reviewed it in Issue 14.

Without the opening note about fantasy being escapist, I agree with Ursula K. Leguin’s point. It is “our plain duty to escape” when cornered. We owe it to ourselves and to the principle of the thing. We owe it to others by way of example. When all life on Earth is extinguished and there’s a final accounting of things, it would be nice if it could be said (though by whom?) “they lived free.” I mean, that won’t happen now, it’s too late in the day, but one must try. One’s bean must be counted in the right column.

A related point that rolls around in my head is that while fantasy is said to be escapist (though of all the writers to say this, Le Guin’s work bulges with allegory and polemic) it isn’t unreal. A fictional character or world might not occupy the same plain of reality as we do, but when we’re reading, we’re reading. Reading is a real event, happening materially in the material world. So if fantasy is not unreal, can it really be said to be escapist? One doesn’t escape reality into the same reality, does one? Just a thought.

I think I prefer this Ursula quote, where she begins to separate escapism from Escapology:

As for the charge of escapism, what does “escape” mean? Escape from real life, responsibility, order, duty, piety, is what the charge implies. But nobody, except the most criminally irresponsible or pitifully incompetent, escapes to jail. The direction of escape is toward freedom. So what is “escapism” an accusation of?

*

I Already Knew I Would Leave

I was not like them. I very quickly realised where I was, and at the age of seven I already knew I would leave. I didn’t know when, or where I would go. When people asked me, what do I want to be when I grow up? I’d reply: a foreigner.

Isn’t that great? It’s from Waiting for a Hurricane by Margarita Garcia Robayo (a quickie novella in her Fish Soup collection).

The story is about characters stuck in a small Latin American town. They all want to escape and have different designs on how to do it. Some people look for green cards to America by marriage. Our protagonist becomes an air hostess, enjoying brief exits every day while simultaneously building the escape fund.

Seven though. Hah! When, dear reader, did you begin mentally packing your bags?

*

Better Out Than In

Ever since Dear Jeremy quit his job at the Guardian, I’ve missed the useful window into the worklives of others.

Thankfully, Slate now brings us Good Job to fill that gap. People write in with their job complaints and their agony aunt responds. It makes me feel glad to no longer have a jay-oh-bee.

This week, a correspondant tells the world about their colleague’s farting:

I have a co-worker who has terrible flatulence. He is an absolute misery to be around as a result.

He comes through our floor at least three or four times a day and afterward, the place stinks like a broken septic tank. The rub is that he’s also the head of our department and twice a week our team is required to meet with him to give updates on productivity and other things. These meetings usually are around an hour long, and by the time they are over I’m nearly sick. My other colleagues are similarly at the end of their ropes.

Oh baby. I used to sit next to an office farter. It was all too much. I sympethise with the letter writer.

At the same time, I’m not without sympathy for the farter. Someone wrote to New Escapologist once (hello!) to say that having to hold in your gas all day is something to hate about office jobs. So maybe the farter is also an Escapologist; maybe they want out too. And, as the wisdom goes, “better out than in.”

Sorry. Any future excerpts from this work advice column will be more Escapological and less, um, enterological.

That said, if you’re not too queasy for another worplace methane anecdote, here’s a passage I cut from The Good Life for Wage Slaves on grounds of good taste:

A patronising and overfamiliar IT guy with too much testosterone sauntered into our department one day for his usual unwanted chit chat. He sniffed the air and said “who’s got something tasty for lunch? Something garlicky?” Nobody had anything out for lunch. He’d smelled one of my farts. And liked it.

*

Letter to the Editor: I Have Just Stepped Off the Hamster Wheel

To send a letter to the editor, simply write in. You’ll get a reply and we’ll anonymise any blogged version.

Reader H writes:

Dear Robert,

In June 2016 your book saved me. I was burnt out after years of struggling as a single parent and working three jobs: cleaner, teaching assistant, and weekend shop assistant. As well as having ongoing counselling for a traumatic childhood.

I was trying so hard to make a life worth living. I ended up on antidepressants as my doctor suggested it was depression and not, as was the case, burn out. The antidepressants made me feel worse, unable to get up, washed, dressed. I felt I was at the very bottom of a deep black hole trying to claw my way out.

A friend forced me out of the house in Southampton and dropped me in the middle of Reading high street while he made sales calls in the area. Unable to face people, I found the nearest bookshop to hide in. The assistant asked what I was looking for?

“Anything about escaping life without hurting the people I love?”

Looking perplexed he led me to the “positive mental attitude” books. I searched and searched until a title caught my eye. It was called Escape Everything!

I read your book over and over. I was in that bookshop for three hours and he left me be while I read it over and over. It was exactly what I felt… life had become one long struggle of trying to make ends meet. Nothing else.

I arrived home a different person. I came off the antidepressants, wrote up my escape plan and worked my bollocks off!

Fast forward through some incredibly hectic years. I have renovated many unloved properties (my passion), giving them back their dignity and mine. I have just stepped off the hamster wheel And have many creative ideas still to pursue!

Thank you from the bottom of my heart for dropping a ladder into that hole.

To this day it is my bible. I am free to live the life I want to live and life is bloody amazing!! 😘

Thank you.

*

Foof. It’s hard to know how to respond to this one other than to say thank you for taking the effort to tell me. You’re welcome. And your new life sounds beautiful. You’re the one who did it though: you planned and acted, which is what it all comes down to. Congratulations.

Going Out the Door One Day and Never Coming Back

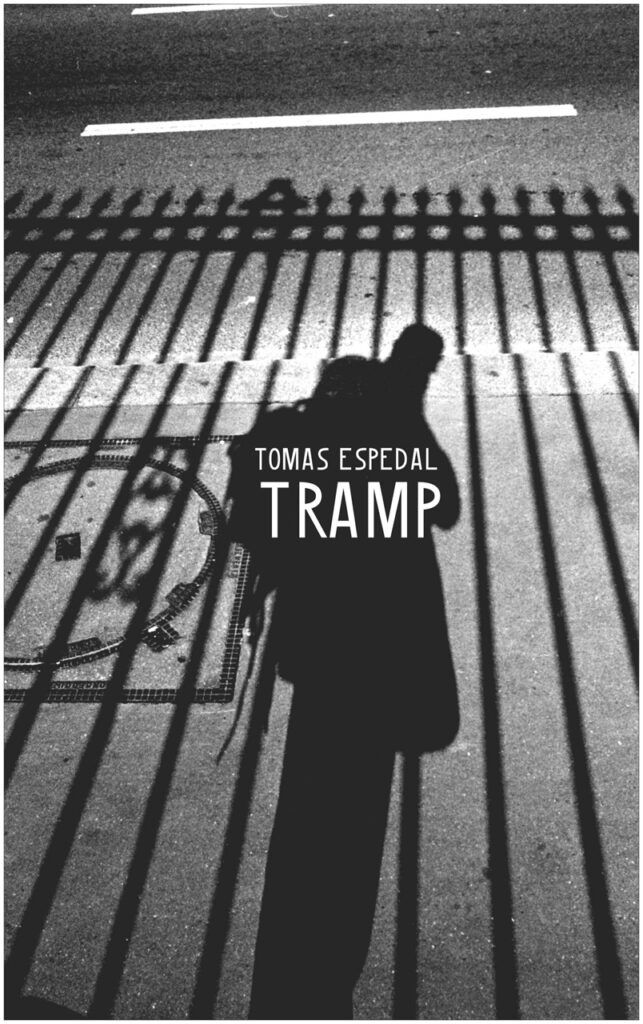

Thank you to the New Escapologist reader who put me onto Tramp (2006) by Thomas Espedal. It’s an excellent book. Not quite a novel, not quite a travellogue, it flies by like poetry.

Espedal doesn’t want to settle down:

I’d never been fond of houses, they were too large and unaccomodating. A house is demanding, difficult. One must learn to master a house. One must learn to dwell.

… superfluous rooms, the hostile furniture, this semi-temperate interior that speaks to us of our wasted work, our misused moneys, our dull lives.

He just wants to escape:

The Dream of Vanishing. Disappearing. Going out the door one day and never coming back.

He wants to keep on walking:

The wanderer is, according to Rousseau, a plain, peaceful man. He is free. He has left the city, he has left his family and obligations. He has said farewell work. Farewell to responsibility. Farewell to money. He has said goodbye to his friends and his love, to ambition and future. He is really a rebel, but now he has bidden farewell to his rebellion as well. He wanders alone in the forest, a vagrant.

Or gliding along by rail:

I like sitting on a train looking out of the window; seeing the landscape roll past while I tentatively read a novel: Vaksdal, Trengereid, Dale, Evanger, Voss, and the first snow, the first frost, the first kiss in the snow on the frozen stone wall down by the lake shore at Vangsvatnet; winter, summer, spring, and the train rolls past.

These are just some choice quotes that reflect our (or maybe just my) tendencies here at New Escapologist. Espedal likes other things too, such as mountaineering and driving fast cars. He’s just a guy who loves life. This comes over on the page, but quietly and elegantly so. What a great book.

Also noteworthy: Espedal walks (and climbs mountains) not in sportswear… but in a suit!

*

Sympathy with the vagrant? Issue 16: Footloose and Fancy-Free is your companion. Prefer to stay put? Issue 17: All the Way Home is yours. Open minded? Get both!

A Postcard From Monterey, c1955

It was a maximum-security prison. There was just no easy way out of it.

This guy isn’t talking about Manus Island. He’s talking about midcentury American suburban life.

After years of being “a model citizen,” he says, he dropped out and went to Monteray, a centre of counterculture, within proximity to the ocean.

And all the while I knew I had put the bars there. I’d been constructing this thing since the time I was a child.

Thanks to readers Lauren and Joe for sending this in. (It has nothing to do with LSD, by the way. The title is clickbait but it’s a lovely video).