Learned Helplessness

I’ve been reading books about prison. The best one so far is probably A Bit of a Stretch, the prison diaries of filmmaker Chris Atkins.

Here’s Chris Atkins on self agency, the ability to steer your own course through life:

Much has been written about whether we have a hand in our own destiny, but at least in the outside world it feels as if we have some involvement in our fate. Prison not only robs inmates of control, but also denies them the illusion of agency. They are constantly reminded that they have no impact on anything, which has long been cited as a cause of mental illness.

He goes on to describe Jay Weiss’s 1971 psychology experiments in which rats were trained to avoid electric shocks by pressing a lever. The rats became vigilant of this, but then Weiss changed the rules so that the levers no longer worked. The rats went through a period of pressing the lever regardless (“but… but.. it always worked in the past!”) and then they fell into a period of depression.

Atkins says this has a striking similarity to the effect of “call bells” on prisoners, which supposedly exist for inmates to call a guard for help or attention. Much of the time, however, their calls go ignored due to low staffing levels caused by politically motivated funding cuts.

When Atkins was in prison, the call lights on the outside of cell doors would flash ineffectively almost all of the time, their occupants becoming steadily more desperate and then hopeless.

This is known as “learned helplessness.”

Learned helplessness exists in other areas of society too: in childhood, university, jobs, hospitals, visas and immigration. It is designed to prevent escape.

Escape, hope and agency are intertwined. Dare to dream of escape, dare to hope, dare to act.

*

For ideas on how to escape, try I’m Out (formerly published as Escape Everything!) and for a shoulder to cry on, try The Good Life for Wage Slaves.

The Indulgence of Sleep

A brilliant passage from Shola von Reinhold’s LOTE, which is so far my novel of the century.

“A lack of sleep leads to fascism, you know, Griselda.” I decided it would be a good time to expound my theory: the sort of people who claim to require a few hours a night frequently happen to be morally bankrupt. This did not include people who couldn’t get a decent number of hours’ sleep because of insomnia, work or children and so on, but rather people who claim not to need it and thus exhibit their own productiveness. These people included various right-wing politicians, dictators and numerous CEOs, regularly dubbed “The Sleepless Elite” by business magazines. Implicit in their claim is that everyone in the world aught to relinquish sleep if they want to escape hardship. That you are being indulgent. Perhaps their own lack of sleep causes this way of seeing: they are seriously sleep-deprived without realising they are, and after this long-term deprivation, their capacity for empathy has dwindled.

I remember something Tom Hodgkinson said in the Idler in the late ’90s: he was responding to Tony Blair making the perennial Thatcherite claim that he doesn’t sleep very much and in fact doesn’t dream. Tom contrasted Blair’s strange boast to Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream,” arguably the most affecting and important political statement of all time.

I suppose the dictators and CEOs observed by Shola von Reinhold think they’re being stoical or independent-minded in some way with their claims to supernature, but it’s hardly inspiring to have a leader who boasts of being deprived and, in Blair’s case, unimaginative.

If you’re looking for new year’s resolutions, you could do worse than buying and reading LOTE and learning to nap.

More Tove

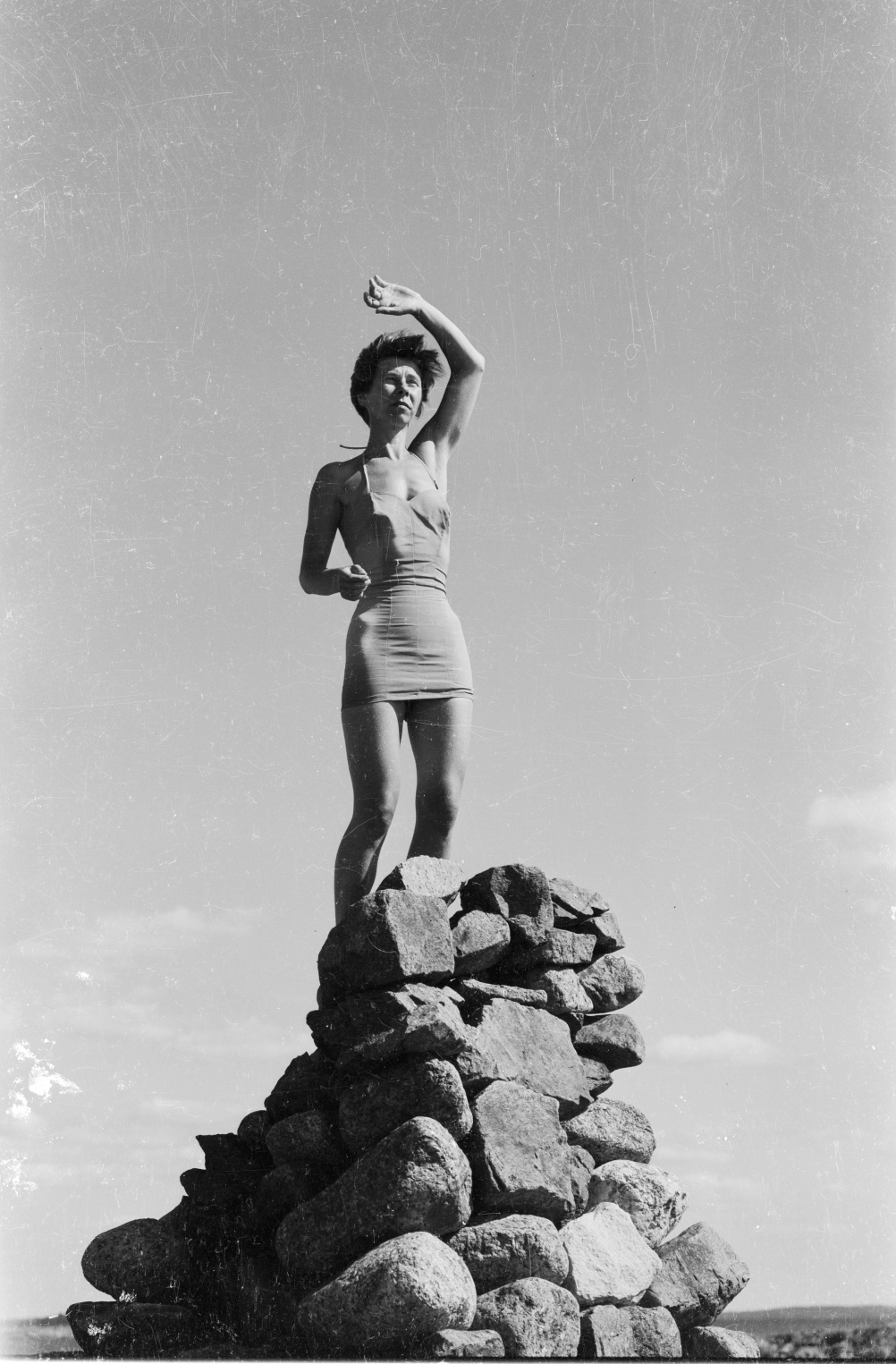

Further to our previous post, there’s a nice documentary on YouTube about the freedom- and adventure-loving life of Tove Jansson.

There’s also the following hour of archive footage, some of which was used in the documentary. None of it is in English but if you have a big screen or a projector in your home (alas I do not) it could still provide some cheerful ambient company.

Tove Jansson: Love and Work

I recently read Fair Play by Tove Jansson.

It’s a work of fiction drawing heavily on Jansson’s later life, shared with her artist partner Tuulikki Pietilä. Together they make art, bicker playfully, obsess over movies, walk in nature, receive visitors. Sometimes they live in the city and sometimes on an unpopulated island.

In the foreword to the edition I read, Ali Smith describes the novel’s main themes as “love and work.” This is correct and it’s a fair reminder that “work” is not the true thing an Escapologist finds objectionable. For example, we’d probably value the flow and the consensual nature of small art production. It’s the submission of employment and the competitive brutality of business that we object to.

Fair Play is stuffed to brim with depictions of love and “the right kind of work.”

There’s also a collage of photographs on the inside covers, which I found relaxing to look at. I present them here along with some Escapological quotes from Fair Play (and some from my follow-up reading).

Some people just shouldn’t be disturbed in their inclinations, whether large or small. A reminder can instantly turn enthusiasm into aversion and spoil everything.

It is simply this: do not tire, never lose interest, never grow indifferent—lose your invaluable curiosity and you let yourself die. It’s as simple as that.

What was it we were so busy with? Work, probably. And falling in love – that takes an awful lot of time.

From AnOther magazine:

when you trace the secret history of [Janssen’s] life, [you discover] an instinct to live by her own rules, from childhood to her death aged 86.

From Jansson’s The Summer Book (1972):

A person can find anything if he takes the time, that is, if he can afford to look. And while he’s looking, he’s free, and he finds things he never expected.

Mari was hardly listening. A daring thought was taking shape in her mind. She began to anticipate a solitude of her own, peaceful and full of possibility. She felt something close to exhilaration, of a kind that people can permit themselves when they are blessed with love.

They sat in their separate chairs and waited for Fassbinder, their silence a respectful preparation. They had waited this way for their meetings with Truffaut, Bergman, Visconti, Renoir, Wilder, and all the other honored guests that Jonna had chosen and enthroned–the finest present she could give her friend.

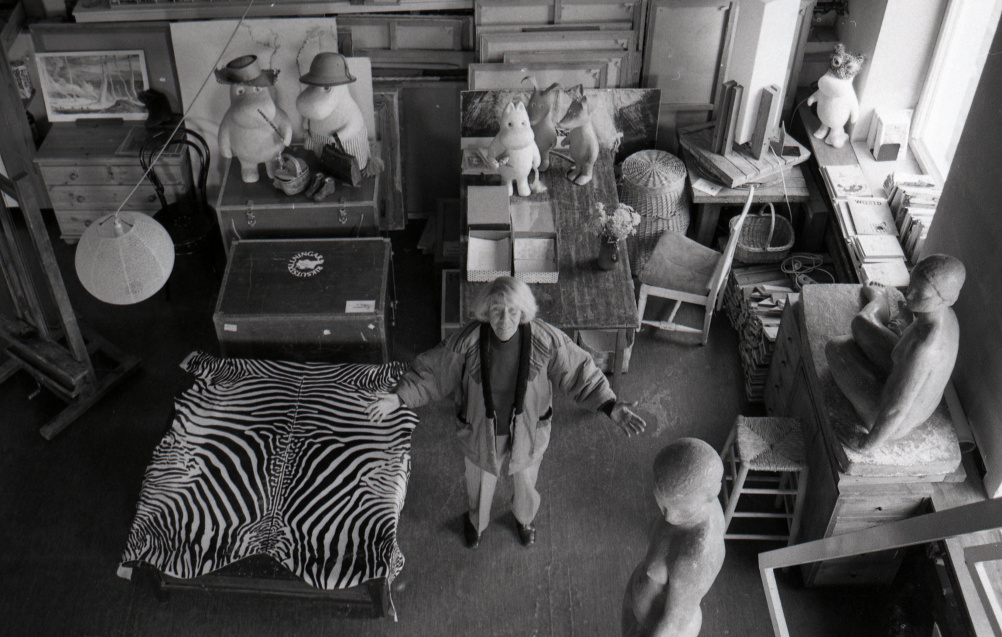

And here’s the obligatory picture of Tove with her most famous creation, the Moomins.

From Finn Family Moomintroll:

Don’t worry. We shall have wonderful dreams. And when we wake up it’ll be spring.

Substacked

The New Escapologist newsletter is now administered with Substack. We used to use Mailchimp but it became increasingly rubbish so this move is long overdue.

I spent an inordinate amount of time today transferring the newsletter archive to Substack. The usefulness of this is limited when you remember that the newsletter’s content is largely a digest of these blog entries, but it somehow seemed VITALLY IMPORTANT today for me to standardise the titles and ensure each edition has its own little preview image. Job done.

The new archive is pleasant to browse should you want to. You can also leave comments beneath any edition. Fun!

Here’s where to join if you don’t already receive a monthly newsletter by email.

Gobbing Off

“Goblin Mode,” the Guardian reports, has been added to the Oxford English Dictionary.

The real story is that the term was voted in by landslide popular demand. Well, I’m glad it defeated “metaverse.”

As you probably know, “Goblin Mode” refers to “unapologetically self-indulgent” behaviour, “lazy, slovenly, or greedy, typically in a way that rejects social norms or expectations.”

Seemingly, [the term] captured the prevailing mood of individuals who rejected the idea of returning to ‘normal life’, or rebelled against the increasingly unattainable aesthetic standards and unsustainable lifestyles exhibited on social media.

I like that idling is suddenly so popular that its given rise to new terminology, but of all the fantasy creatures I’m not sure why goblins get the rap for this. Aren’t goblins quite busy and avaricious, general makers of mischief? Why isn’t it “ogre mode” or “bogeyman mode” or “swamp monster mode”? I’d say the kids don’t read enough, but Shrek’s an ogre and everyone loves Shrek.

Meh! I like lampin’ better.

Thirsting for a retreat into Goblin Mode? Try The Good Life for Wage Slaves or I’m Out, both of which are available now in paperback.

Giant Bug Monster

This human on Twitter mentions the “giant bug monster” from The X-Files “that pretends to be upper management at a call centre.”

And they share a nice behind-the-scenes photograph.

I remember that guy! The episode you’re looking for is called Folie à Deux and it’s delightful.

Is YOUR boss a giant bug monster? Try The Good Life for Wage Slaves for a shoulder to cry on or I’m Out to plot your escape.

“You Got to Do What You Got to Do, Right?”

I’ve been listening to a fair amount of This American Life. I guess I just dig vocal fry.

Sometimes, the show tells an escape story but I usually forget to mention it here because I listen in bed and forget all about it by sunrise. Miraculously I have remembered one.

“Who is Ryan Long?” tells the story of a game show contestant called, well, Ryan Long. He did extremely well on TV’s Jeopardy!, winning almost $300,000.

Ryan was introduced to the telly-viewing public as as a rideshare driver but he’d actually been something of a factotum. Throughout his thirties, he’d worked in airport security worker, as a package handler, an office clerk, a piano mover, a warehouse worker, a “water ice guy”, a cashier, a bouncer, and a street sweeper. He says, “You got to do what you got to do, right?”

Ryan is biracial and physically large, which apparently isn’t the typical profile of a Jeopardy! contestant. His confounding of prejudice is the thrust of this programme about him, but the presenter goes on to say:

I also got this accidental reflection on American capitalism, and how so many of us are served so poorly by the way life is currently set up as all work and no time. Jeopardy provided a very specific Ryan-shaped escape hatch. It gave him the space to stare into that crack between realities, and fish out all the elements of what his life could be.

We’re all too often told that work is liberating, that it’s what we have to do to “get ahead” but the rewards are often so low (and increasingly so) that all we get in exchange for our graft is our home and healthcare if we’re lucky. We do not generally find the time for personal improvement or to give anything worthwhile to our communities beyond the demands of capitalism.

This “accidental reflection” came about when interviewer asked Ryan if the prize money had made him happy.

It allowed me the opportunity to have time to […] examine myself, I guess. Just everything before, looking where I come from and what makes me tick. It’s a valuable thing. I think everybody needs to do it, but not everybody has time to do it. […] That’s the most valuable thing that I got out of this.

It’s an example of how a life-changing sum of money (though still not the millions of dollars some people imagine they’d need to retire) led to the buying of time to do the personal work, to take stock and come to terms with one’s emotions, to defrag, and see what’s going on with yourself.

No doubt Ryan will go back to work and maybe he still does a few rideshares even now, but the time he bought with the prize money allowed him to be himself for a while.

I wish more people had the chance to engage in this kind of reflection, for mental good health and for actively figuring out what to do next. We’re too often shoved around with no time–the naturally-occurring time of our lives–to spare. We’re told that Universal Basic Income (the provision of material basics for everyone, so that work becomes a consensual choice instead of wage slavery) would lead to personally unproductive or “immoral” slacking but Ryan, this clever everyman, joins a growing body of people who can show otherwise.

Tired of the everyday grind? Try The Good Life for Wage Slaves or I’m Out, both of which are available now in paperback.

How You Can Help Elderly Relatives Escape from Hospital

An item in the Guardian this week has the strange title, “How you can help elderly relatives escape from hospital.” You get Emily Dickinson’s thrill from the word “escape” and the instructional tone, but it’s also slightly troubling in that you wonder why anyone would need to escape from hospital, a place designed for wellness and recovery. It brings to mind dark hospital fantasies like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The Kingdom, and Toby Litt’s Hospital. To be honest, I prefer Scrubs.

Yet here we are. The NHS in Britain is struggling after 12 years of Tory austerity exacerbated by Hostile Environment policies and Brexit. Equally frightening is a staffing and facilities crisis in social care. The twin crises have led to a Kafkaesque situation where maybe a third of hospital beds are occupied by people who don’t need to be in hospital. They’re no longer ill but they can’t leave because there’s no facility in social care to help them with essential mental health or mobility issues.

The newspaper item consists of two letters from people who have helped their relatives escape. One writer describes how they registered with the Office of the Public Guardian to get jurisdiction over their mother’s care. The other describes how they simply bundled their aunt into a warm dressing gown and left.

It’s a perfect illustration of the two main modes of escape. You can use knowledge and patience to deploy bureaucracy against the force that holds you, or you can be agile and just go. The former is often smarter and can solve longer-term problems like what to do when you’re all out of runway or if they come running after you. But, oh, the courage and dignity of the latter! I’ve done both.

This hospital example also reminds us that an escape isn’t just good for the person doing the scarpering, but good for everyone else too. Those vacated hospital beds were doubtless desperately needed. Escape can be socially useful as well as personally liberating. Better you do something useful or beautiful for the world than tirelessly punching a clock, for example.

I suppose this is as good a time as any to remind UK-based readers to vote against the Conservative Party at the next available opportunity.

Velo Flaneur

Here’s a pleasant blog from a mellow escapee.

It’s by the artist formerly known as Reader M in fact. Fergie’s Journal of Life in the Slow Lane charts quiet adventures in gardening, cycling and general unusedness during early retirement in a foreign land. Lovely stuff.