Making the Transition

Highwire artist Philippe Petite, who crossed the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre in 1973, says:

Once I’m on the wire it’s alright. It’s the moment of transition from the solidity building to the wire that’s frightening.

I’ve written about Petite before because I love the documentary Man on Wire (2008). The above quote is from the drama film The Walk (2015), which means the quote came from a fictional version of Petite. Maybe it has basis in reality, maybe it doesn’t. I am not above quoting from fictional people.

In any event, it contains wisdom. Take it from me that once you’re out there — away from a secure income, in the wilds — all is well. It’s the trepidation that’s the kicker.

I was thinking about this today I tried to write something substantial for the first time since recovering. It felt scary until I got started. The only hump to get over was beginning. Once I got started, I was in full swing. Whatever it is, just start. Make a mess of it. Then make it better. Then you’ll find flow. “Look, ma, no hands!”

*

Please subscribe to New Escapologist by backing our Kickstarter campaign. w00p!

Zombie Sighting

Gabriel Josipovici’s pandemic-era diary and essay collection, 100 Days, is full of wisdom, wit, and rage. But look at this:

F, many years ago [asks me] ‘why do you lay the table for breakfast the evening before? You might want quite different food or no breakfast at all.’ I try to explain that when I come downstairs to make breakfast, I don’t really want to have to think, just to make it automatically, since I don’t feel properly awake til I’ve had my cup of tea.

I am vindicated! He harnesses the zombie!

*

Please subscribe to New Escapologist by backing our Kickstarter campaign. w00p!

The Unthinking Steps

There are seven flights of steps up to our flat: six main ones plus the one that takes you up to the main staircase from the ground level. I call that first flight “the unthinking steps.”

Basically, I find the ascent of the stairs really boring. There are small things I can do to alleviate the boredom, such as fishing the door keys out of my pocket, but there aren’t enough of these small things to occupy my mind all the way to the top.

So instead of squandering my “entertainment” on that very first flight, I try to empty my head of thoughts completely. It’s a little exercise in mindlessness.

It doesn’t always work. Once I’m in the building, I start thinking automatically about the things I’ll do once I’m home. But I try to quash that automatic process for the few seconds that it takes to climb the unthinking stairs.

The idea is to survive the boredom of the repetitive ascent up the stairs. But it’s also to slow down, to stop planning or letting the mind fly too soon into the future.

Do you have an unthinking stairs or similar?

*

Ennui

By “the problem of leisure,” Stuart Whatley in the New Statesman (a generally left-wing periodical) refers to the idea that most people wouldn’t know how to spend their time if they no longer had to go to work. Or, worse, that they would spend it deleteriously. It’s the “lotus-eater” theory in which we all become the obese layabouts of WALL-E. I’ve always found this to be a deeply conservative and patronising position. My position is that, after a period of idling, most people will want to act, to help themselves and the world in some way. But what if I’m wrong?

Over a decade of writing and thinking about modern work and its opportunity costs, I have generally mentioned the “problem of leisure” only in passing, largely because I would like to believe that it is soluble. Yet the political situation in the United States (and some other industrialised democracies) demands a reckoning, and it cannot be understood without reference to misspent leisure.

Whatley worries, basically, that the nihilistic politics that led to Trump and Vance in the US (and to Starmer and, perhaps inevitably, a PM Farage in the UK) and to an inward-looking rejection of optimistic internationalism, was caused by an ennui inherent to increased and misspent leisure time coupled with a lack of interest in boring or bullshitty work.

I’d argue that leisure time isn’t increasing, not in recent years anyway. It increased over the 20th Century for sure, thanks to well-organised labour movements, but we’re in the gig economy now, where, for many, every hour has some small cash value and must be hungrily seized upon as a matter of survival. I can’t deny, however, the sort of alienation from work he describes seems to be increasing (it’s certainly why I wanted to escape) and the likelihood that some people fall into a Leisure Trap of “an endless stream of video content or chocolate cake or edibles or any other indulgence cannot deliver lasting satisfaction. Everything gets old eventually, leaving one to grope around for the next fix.”

It’s the reason, I think, that there was no post-pandemic cultural renaissance comparable to the last century’s interwar years. We didn’t have it bad enough in the pandemic. Netflix and YouTube made it just about acceptable to be stuck indoors all the time. Some people even preferred life that way. I’m forced to accept that the ennui Whatley speaks of probably exists.

And yet he does not give up on my sort of optimism:

Yet solutions to the problem of leisure exist throughout our own wisdom tradition, which stresses the value of friendship (Epicurus), contemplation (Aristotle), and “other-regarding” public service (Cicero). These basic human goods have been severely eroded, producing an age of loneliness, inattention, and ginned-up tribalism; but each could be reclaimed with sufficient free time and a proper command over it. While there will always be demagogues, conspiracists, and cult leaders, they would have no purchase over a people who can find fulfilment in themselves.

*

An Escapologist’s Diary: Part 83. Marrow.

Dear Diary, my troubles lie ruined and in my wake. After a long period (almost six months) of debilitating illness, I seem to be well again.

I visited my parents in England last week (the change of scene alone being just the tonic), was reunited with the crew to actively work on the film again, and now, at home, I work quite happily in a way unthinkable just a few weeks ago.

This boom in pleasant activity is coupled with a thrice-weekly hospital therapy. It’s too soon to say if the therapy is helping (I think I got better naturally) or will help to keep the condition from returning, but I enjoy the walks to and from the hospital. It takes me through a leafy neighbourhood of beautiful townhouses and, since the weather has been good, these morning walks are accompanied by glorious birdsong.

In terms of creative work, I must not overexert myself lest doing so should lead to a resurgence of the illness, but I’m so keen to make up for lost time. Finally out of bed, I want to eat the world and suck at the marrow. And that appetite in its own self feels good.

So I’ve been working on the film as I previously mentioned, socialising somewhat, closing in on the end of an editing project (the first major thing I was able to pick up, editing being easier than writing during a medicated brain fog), and lining things up for an 18th print edition of New Escapologist. On that note, please chip in to the Kickstarter if you have not already, as everything depends on its success.

There are meds I no longer feel obliged to take, the ones that make me fall asleep. This is good. The step counter on my phone has numbers on it again. Green shoots!

I have shaved off my beard of convalescence! I’m enjoying dressing well when I go out, so utterly tired of ointment-caked PJs.

All for now. I just wanted to register this development in the diary, to announce that I’m moving on from the shitness of illness, that, suddenly, everything seems possible. And not a moment too soon.

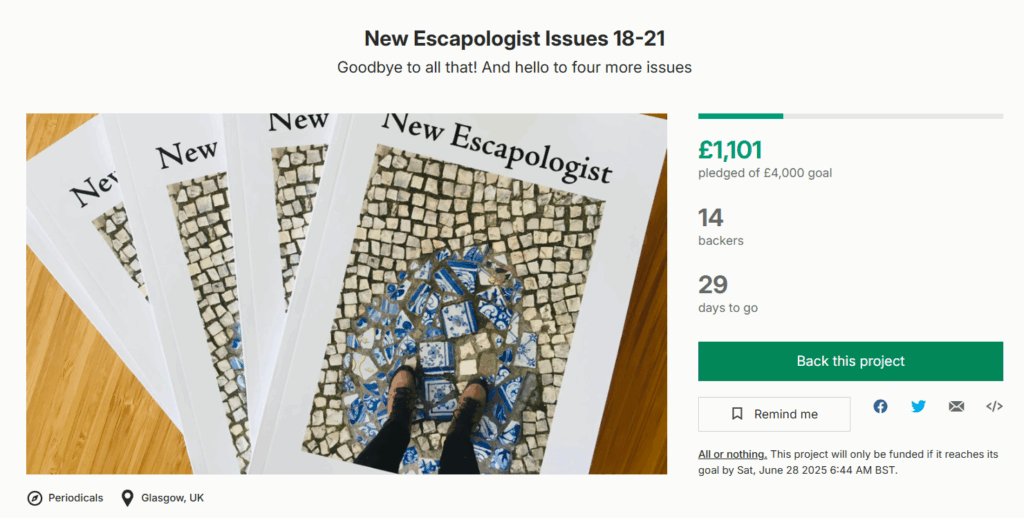

Kickstarter Loves Us

Well, we got halfway to target on Day 1, which bodes well, but I’ll be a nervous wreck until we actually cross the line. So here’s where to go if you’d like to ensure New Escapologist lives on for another four editions. Thank you, as ever.

And I’m not sure what this means, but Kickstarter loves us:

*

Tired of the everyday grind? Back New Escapologist on Kickstarter today.

Here We Go Again!

Dear readers. It’s 2025 and time for another Kickstarter. Here we go again!

Let’s see if we can raise enough money to push New Escapologist into 2027 with another four print editions.

Please back the Kickstarter here. Thank you. x

We first began in 2007, lasting for 13 issues over the next ten years. Then, in 2023, Kickstarter enabled us to bring the magazine back for a second volume (Issues 14-17). We’d now like to continue that second volume for four more issues (18-21, all the way to the summer of 2027).

Over the years, we’ve had some top-drawer contributors including Alain de Botton, Will Self, Richard Herring, Judith Levine, Luke Rhinehart, Leo Babauta, Mr Money Moustache, Momus, Ewan Morrison, Caitlin Doughty and many others. We’ve also featured great writing from working stiffs looking for ways to leave it all behind.

New Escapologist Vol.2 has seen some of our best work to date: essays, book reviews (of old and new books), film reviews, columns from clever people like McKinley Valentine, David Cain, Apala Chowdhury, Jacob Lund Fisker, Henry Gibbs, and the Idler’s Tom Hodgkinson, interviews, escape tactics, views into the Old Web, and letters to the editor.

Wise Course

From A Haunted Hotel (1878) by Wilkie Collins:

He decided forthwith on taking the only wise course that was open under the circumstances. In other words, he decided on taking to flight.

To his servant, this character says:

Now then, softly, Thomas! If your shoes creak, I am a lost man.

*

Normal

From a photography article in the Guardian:

I discovered they were 29-year-old twins who lived nearby in a tent, in woodland behind a friend’s trailer home. These boys had never learned how to have a “normal” life – how to organise everything, show up to a job, all the basic things.

It’s another reminder of the richness and variety of human experience. Worried about quitting an office job for something more rewarding, or downsizing to a smaller property so that you don’t need so much money? Well these guys live in the woods. And they always did.

*

Idlerfest ’25

I’ll be at this, doing 45 minutes on “how to escape the daily grind.” See you there and then? Top hangout opportunity if ever there was one.