An Escapologist’s Diary: Part 71. Germany und Switzerland.

Dear Diary, I write to you from continental Europe, where I’m basically on vacation but where I’m also conducting research for the magazine. It feels good to be footloose, blasting through the deep green countryside on Swiss and German trains.

In Freiburg, I visited Jonathan at Analog Sea, a publisher and cultural institute whose work I’ve admired for the past four years.

An early subscriber to New Escapologist, Jonathan is the real deal and his little team do everything the right way. As well as promoting real culture and philosophy, they’re deeply committed to staying offline: they have almost no web presence and Jonathan talked to me about the challenge of resisting Amaz*n who can still apparently devour the data and labour of those who make special efforts to avoid them.

As well as exchanging ideas and information about independently publishing a small press magazine, we recorded an interview for publication in a future New Escapologist. As we talked, my partner, Samara, sat quietly by and drew our portraits. It tickled! But it also felt like the sort of convivial creative moment that might lead to even bigger and lovelier things.

In Weimar, Samara and I visited the original Bauhaus University. We were expecting to join a walking tour but either it wasn’t running or we’d misunderstood the rendezvous point. We were ready to leave, thinking, “well, at least we came to the spot where it all happened,” but then I decided we should just enter the main building anyway.

I worked at Glasgow University for a while and it always amused me that, while the beautiful campus and many of its buildings were open to the public, few people ever ventured into the cloistered space. So, in Weimar, we burst inside uninvited to see frescoes and statues dating back to Bauhaus’s pre-War era and even a bust of founder Gropius himself.

Our covert explorations stopped, however, at the door of the Director’s Office which was, perhaps sensibly, locked. We hung around for awhile in case the scheduled tour group should appear and the guide unlock the door to afford us an undeserved peek, but it never turned up. The only other people we saw were a couple of hurried lecturers retrieving paperwork from their own, presumably less pretty, offices.

Less covertly, we visited the nearby Bauhaus Museum where, among other things, we saw independently-published books, artwork and pamphlets that may yet inform the future look of our magazine. Rest assured, it won’t be too fancy and we’ll keep it cheerfully cheap. In fact, that was a point of inspiration: talent and resourcefulness (and the use of technology unavailable to Gropius and his friends) can make up for modest funding.

In Basel, our EasyJet Hotel room felt ominously like a prison cell, bewilderingly small, with no window and with a toilet in the room. Avoid it, mein kinder! It was considerably worse than any hostel dorm or €9-a-night Turkish flop I have stayed in. It was almost worth the not-particularly-low price to see the spectacle of it. I have asked for a refund, which, if successful, will go into our printing fund for the magazine.

*

A confession, oh secret diary. There’s a vacancy at a library in Edinburgh. It’s a very dignified and well-paid job and, before our trip, I was tempted to apply for it.

Were I to get through the interview, the job would have salted my mild but persistent money anxieties once and for all and my days would have been filled with fairly pleasant and bookish work. On the other hand, it would have scuppered the New Escapologist comeback and probably also any future books I might write. I would have accepted the offer with a heavy heart.

Fortunately, the trip put paid to this rare temptation to grapple with a job application. My desire to create and to be on the front line of cultural production instead of merely toiling in support of it has been redoubled. I have Jonathan and Elena at Analogue Sea–and Bauhaus’s Kandinsky, Schlemmer and Klee speaking to me through the years–to thank for that. Another narrow escape, perhaps.

*

If you enjoy this blog and would like to see the return of a real New Escapologist magazine, you can help by buying my book The Good Life for Wage Slaves. Also still available are bundles of New Escapologist in print (1-7 and 8-13) or PDF (1-7 and 8-13). Anything you buy will help me to further this tiny non-profit enterprise.

Letter to the Editor: As Into a Quicksand

To send a letter to the editor, simply write in. You’ll get a reply and we’ll anonymise any blogged version.

Friend McKinley writes:

The “vast grey sleep” reminds me of a line from Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s memoir, Wind, Sand and Stars, when he catches the bus to the airfield for his first ever mail run as a pilot (which was very risky and glamorous at the time).

Finally I saw the old-fashioned vehicle come round the corner and heard its tinny rattle. Like those who had gone before me, I squeezed in between a sleepy customs guard and a few glum government clerks. The bus smelled musty, smelled of the dust of government offices into which the life of a man sinks as into a quicksand.

I see now that I had misremembered it. He’s comparing the office dust to quicksand. I had the phrase remembered as “one of those government jobs into which the life of a man sinks as into a quicksand,” which certainly feels like the people I know who got a job in the public service with every intention of getting out in a year or two. He’s saying the exact same thing, just sticking closer to his metaphor.

I now have this sudden fear that I first came across the line in Escape Everything! and it’s what prompted me to read Wind, Sand and Stars in the first place, the timing is about right. Regardless!

*

Wringham Wresponds:

That’s a nice quote and it’s not one from Escape Everything!. The closest thing I remember quoting is this moment from a J. M. Coetzee memoir.

Something I failed to note about that quote is that, as well as being an early example of using a computer to skive, it’s an early example of computer programmers working devotedly for no extra money into the night.

This End Up

Further to yesterday’s post, the idea of packing oneself into a crate and travelling covertly to another land is not without appeal.

Even I, a tall man, quite like the idea and I don’t even have much to escape at the moment. I just like an adventure and good deal. Besides, can’t be much worse than Ryanair.

All of this has, of course, reminded me of the Welsh teenager Brian Robson, who mailed himself home in a crate from Australia in 1965. He described the experience as “quite horrific,” taking four days and frequently being stored upside down. Robson’s box was redirected to the US, where he was found and then grilled by the FBI before being repatriated to London (so it sort-of worked).

And then Wikipedia has a list of others who have achieved (or failed) similar feats:

[Athlete and smuggler] Reg Spiers mailed himself from Heathrow Airport, London, to Perth Airport, Western Australia, in 1964. His 63-hour journey was spent in a box made by fellow British javelin thrower John McSorley. Spiers spent some time outside his container in the cargo hold of the plane and suffered from dehydration [by the time] he was offloaded onto the tarmac of Bombay Airport. He arrived in Perth undetected and returned home to Adelaide.

Charles McKinley (age 25) shipped himself from New York City to Dallas, Texas in a box in 2003. He was attempting to visit his parents and wanted to save on the air fare by charging the shipping fees to his former employer. However, he was discovered during the final leg of his journey having successfully travelled by plane.

Did you catch that part? McKinley “saved on the air fare by charging the shipping fees to his former employer.” What a legend.

An inmate (age 42) serving a seven-year drug conviction sentence in Germany escaped from a prison by climbing into a box in the mail room which was picked up by a courier in 2008.

Hooray!

*

For arguably more practical ways to escape, try my book I’m Out. Also still available are bundles of New Escapologist in print (1-7 and 8-13) or PDF (1-7 and 8-13).

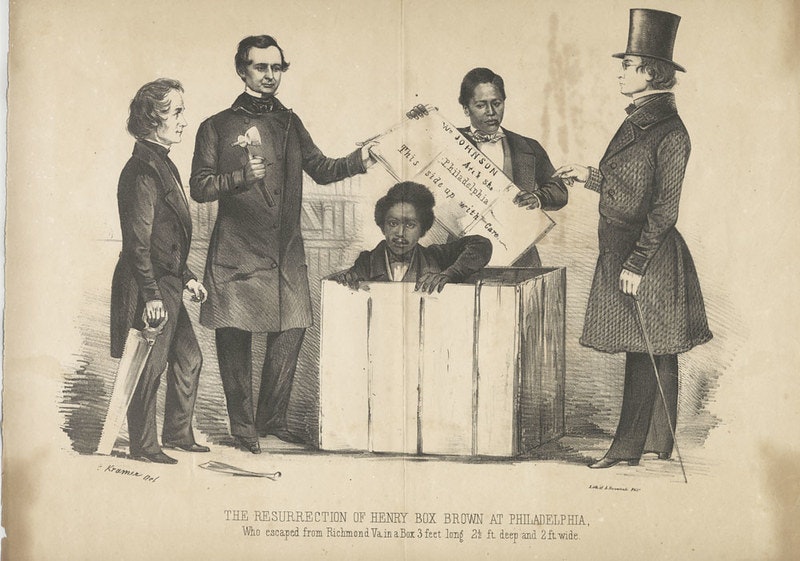

The Escape of Henry “Box” Brown

In the late 1840s, the brilliant Henry Brown found a way to escape slavery.

Sensing, probably correctly, that travel by conventional means would result in recapture, he decided to seal himself into a box and be express-mailed to freedom.

After twenty-six hours of rough handling by deliverymen, he was pried from his [box] and — being a deeply religious man — sung a song of thanksgiving he had written, based on Psalm 40.

As we often like to say in New Escapologist, an escape is best affected with a sense of showmanship and aplomb.

Additionally, there is no more satisfying way to make a living than by turning one’s entrapment (or escape story) into something lucrative. It’s all about the irony of using the machine’s burdensome weight against itself. “Indeed,” says The Public Domain Review,

in the months directly following his escape, Brown took “Box” as his middle name; published The Narrative of Henry Box Brown, who Escaped from Slavery Enclosed in a Box 3 Feet Long and 2 Wide, Written From a Statement of Facts Made By Himself; and went on tour in New England, telling his story and singing songs of his own composition.

Superb.

Here’s a little more from Humanities journal:

Appearing in cities across New England and, later, Britain, Brown attained a form of nineteenth-century celebrity on the strength of his astonishing tale and flair for showmanship. He rode between speaking engagements inside a box identical to the one that had carried him from Virginia, accompanied by marching bands and American flags, before emerging onstage from the cramped conveyance and presenting scenes from his “Mirror of Slavery,” a painted canvas of one hundred scenes mounted on two enormous spools. Various iterations of the act, which evolved into a kind of vaudeville routine following the end of slavery, were performed in the United States, England, and Canada for decades.

Fifty years before Houdini first escaped a box, Henry Brown escaped in a box.

*

For some arguably more practical ways to escape, try my book I’m Out.

Also still available are bundles of New Escapologist in print (1-7 and 8-13) or PDF (1-7 and 8-13).

Observational Comedy of the Interior

Back at my desk I sit and slowly collect money that I can use to pay the rent on my apartment and on food so that I can continue to live and continue to come to this room and sit at this desk and slowly collect money.

Thus spake Halle Burton’s “Millie,” the protagonist of The New Me.

The book is a millennial tale of feeling awkward and not fitting in anywhere, best of all at work, which is an alienating and precarious nightmare.

I like this bit:

I make $12 an hour, the best-paying job I’ve had in more than a year. If I’m paying twelve, they’re paying the agency at least fifteen, up to twenty, so in the middle let’s say eighteen, times thirty-five is $630 a week, times two weeks is $1,260, times two is more than $2,500 a month to have me, the idiot, sit in a chair, doing about four hours of work a week, sixteen hours of work a month, which puts the rate for my actual services at around $150 an hour.

It’s a strange paragraph to like in a novel, let alone to want to share. It’s all just numbers! But I remember those trains of thought while working as a temp. It’s well-observed. It’s observational comedy of the interior.

I don’t remember working out my actual hourly rate like that but I see what Butler means. Sometimes, I’d have so little to do that I’d almost feel guilty for making the money I needed to stay alive. Almost. Because I didn’t ask for that job. Except I did by applying for it. But I had to do that because I wanted to stay alive. Work isn’t consensual in the way most people seem to describe it.

Back to those numbers. I remember finding out that the agency was paid the same hourly rate as my own. My boss was paying double what I was actually getting, for secretively scrolling through Facebook and reading the Guardian and going slowly bananas. The agency was getting paid the same as me for doing nothing, but their share was for openly doing nothing. We were supposed to be at the cutting edge of Quaternary industry in that job, but it was little more than an iron rice bowl.

The saddest financial calculation I can remember making was on my very first morning when I mental-arithmeticed my way to the conclusion that, while I’d already had enough, I hadn’t yet made back the money I’d spent on a new shirt for the job plus bus fare. Urgh. Never forget!

In that weird paragraph of numbers Halle Burton tells us how boring office work can be, how alienating it can be, how the arrangement is primarily economic, how the power imbalance rots minds.

*

Escape! Escape! is all I can say. Read I’m Out to help with your escape plan and The Good Life for Wage Slaves for a shoulder to cry on in the meantime.