Escape the Deathly Humblebrag

[dropcap]Wouldn’t[/dropcap] it be grand to get one back at the Protestant Work Ethic — that outdated bit of software that keeps so many noses to grindstones and so many internal policemen wagging their fingers at us during moments of repose? Wouldn’t it be super to to send one of its cannonballs of self-doubt right back up the pipe where it came from?

Well, I may have found a small way to do so. This won’t end its reign, its entire jurisdiction over our lives, but it would certainly feel good. And once we’ve had one little bash against the system, who knows what we’ll come up with next in the state of confidence that will follow? First, a story.

One of the first offices I ever worked in was the serials department of a big library. One of my colleagues was a very interesting person who loved Buffy the Vampire Slayer. In fact, she was apparently quite well-known in Buffy fan circles for her entertaining fan fiction.

Now, my personal feelings about fan fiction — short stories published online, set ostensibly in the universes of Buffy or Star Trek or whatever — are not wholly positive. Why write on the fringes of someone else’s idea when you could be using your literary prowess to invent your own characters and your own worlds? But I’m not here to judge the merits of fan fiction. What interested me was the level of fame this person had achieved through writing the stuff and also her attitude towards this activity.

She’d come to the office at 10am, the latest time we were allowed to begin the day, with bags under her eyes from a solid night of writing fan fiction or talking to her followers on Livejournal. It was very impressive, the way she put her fan fiction enterprise ahead of her paid work. Why worry about our library when you can escape into the fictional library run by demon expert Rupert Giles? There were no vampires in our library, only zombies, which are far less charismatic.

At lunch time, this weaver of existing worlds would come into the staff room, collapse onto one of the sofas and begin a huff-and-puff diatribe about how much work she had to do. She wasn’t talking about her work in the library though. No! She was talking about her fanfic. “I’ve got three-thousand words to write today,” she’d say on the verge of panic, “and soon it’ll be NaNoWriMo.”

“What’s NaNoWriMo?” we’d ask, already regretting it.

“National Novel-Writing Month!!” she’d say.

What the Hellmouth was going on here? Wasn’t fan fiction a leisure pursuit? Was it not a fun way to engage with something you enjoyed on television and maybe a way of demonstrating your knowledge of that programme to other fans? Why was she affecting this attitude of burnout?

Some years later, in another office, I worked next to someone whose passion was ancient languages. She’d come to work and blow off steam about the sheer number of hours she’d “had to” dedicate to Sumerian transliteration over the weekend. The tone of her claim was very similar to our old fan fiction friend — not quite a complaint and not quite a boast. Aha! So this is what people mean by a “humblebrag!”

A humblebrag (though apparently John Lloyd of Meaning of Liff fame calls it a moast — the cross between a moan and a boast) is when you come into a room, complain to everyone about how busy you are and that you’re close to breaking point, knowing full well that busyness is code for success in a world where success is a little bit taboo and busyness reigns supreme.

Anything good can be positioned as a whinge. Another erstwhile office-mate would routinely and publicly rue a weekend or hen night for how much alcohol she and her friends had chugged through and how sick it had made them. She was forever having her hair held back. Just as the fan-fic writer and the Sumerian transliterator had framed pride in their hobbies as debilitating burnout, this was her way of saying “Oh baby, I know how to have fun,” couched in the framework of a complaint.

[dropcap]None[/dropcap] of this would be the case if the primary programme being run by our societies was something other than the Protestant Work Ethic, the classic humblebrag being “Oh no, I have so much work to do” or “Oh phew, I did so much work today.” In other words, we occupy a culture in which work reigns supreme. Successful people, goes the standard line, have a lot of work to do. And by definition, to be idle or aristocratic or quiet is to be a failure.

It makes no sense, of course. CEOs might toil away around the clock, but so do peasants. Upper-echelon media types might not get a wink of sleep between them, but neither do single parents or the staff of an all-night garage. The nature of the work might be different, but it ultimately results in the same number of hours being rushed down the plughole in the name of Activity. Where is the virtue in the CEO or the aspiration in garage work? They’re just doing what they do, entirely unmoored from morality or meritocracy. That work is virtuous or something to aspire to is meaningless, but the ethic is gone in for wholesale all the same.

In Escape Everything! I suggested that maybe the people who shout important-sounding business waffle into their mobile phones while riding on public transport aren’t ignorant to the fact that they’re infringing on their fellow passengers’ peace and quiet but essentially drawing public attention to how important they are. Their crime isn’t ignorance but a boorish sort of pride. “Perhaps,” I said in the book, “this kind of behaviour is street attire for dullards.” It says “look at me, I’m suffering, isn’t that fine?”

A possible problem with my claim that the humblebrag is symptomatic of the Protestant Work Ethic is that the humblebrag was only observed in 2010 while the Protestant Work Ethic has been around since the Reformation. One struggles to imagine 16th Century serfs, 19th century coal miners, or 20th century wolves of Wall Street being so humble in their brags. Why now?

“If the 20th century was about achievement despite a previously unseen amount of destruction,” writes a thoughtful blogger, “the 21st century is about coping with achievement itself.” There does seem to be a liberal line of thought running through common discourse at the moment inviting us to “check our privilege,” but the kind of people I’ve noticed engaging in the humblebrag today don’t seem the privilege-checking, guilty liberal types. Could it be a working-class phenomenon; that to have and to hold is all a bit too fancy for “the likes of us”? This is not entirely convincing either. I’m inclined to think that that bragging, humble or otherwise, is symptomatic of insecurity or Alain de-Bottony status anxiety and that status anxiety is most likely to raise its head at times we most crave distinction. Let’s not forget that conformity, as Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter tell us in The Rebel Sell, hasn’t been a driving force of consumerism since the 1950s and that since then it’s all been about distinction. And the appetite for distinction, I’d argue, would be most ravenous (a) when what we see as our true identity is stripped away and smacked down by, say, a demeaning and deskilled office job and (b) during times of economic uncertainty like, say, when a rapidly expanding global precariat is struggling to find the beer money with which to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Global Financial Crisis. Happy Anniversary!

[dropcap]Banishing[/dropcap] the humblebrag then is a neat little way of standing up to the Protestant Work Ethic. As I see it, we can combat the humblebrag in a number of ways:

The first is to get reacquainted with the art of boasting properly. Today, boasting has been relegated to dishonest Facebook photography. Strangely, a photograph of yourself cuddling with your partner at the foot of Mount Fuji is not a humblebrag at all but a genuine brag. It says “we had the time, money and organisational skills to reach Mount Fuji! Woop! Woop!”

Non-humble bragging is probably acceptable on Facebook and not in person because the element of distance between you and your friends provides a sort of prophylactic effect — the safe sex of bragging — and allows you to practice plausible deniability: in the unlikely event that you’re called out on being boastful, you can act surprised and say you just wanted to “share.” Also, clicking “post” is a lot less sensitive a transaction than actually saying “We went to Mount Fuji and it was wonderful! Bet you wish you’d been to Mount Fuji!” to your friend’s actual face. But, I say, this is cowardly or at least unsporting when you could be sharing your pride in real life and it is, when you think about it, a rather neutered experience, a sort-of passive-aggressive arms war with your friends. That’s no way to live.

So I say we need to learn how to boast properly again. What’s wrong with reporting a wonderful time? Because nobody likes a show-off? Well, maybe, but there are ways of showing off that are more fun for boaster and audience alike. Instead of disingenuously complaining about the number of hours put into your Sumerian transliteration, tell everyone how proud you are of the breakthrough you made on this project you care about, acknowledging how lucky you are to have found the time to do something like that.

Instead of humblebragging about work, stress, disorder, calories burned on the treadmill, calories accumulated through cake, we could brag properly about leisure, luxury, skill, success, beauty. We can use phrases like “It was wonderful!” and “I’d never seen so many carnivorous plants!” and “So much delicious cake!”

A brag need not even be about yourself, but about something you’ve seen or, ideally, your shared environment with the person you’re talking to. A cheerful “Did you see the snow on the mountains yesterday? It was great!” is far better than “The streets will be blocked with snow soon. Just great.”

A second, perhaps more advanced approach, is to parody the humblebrag. One could say “Oh, man, so much sex, it’s torture!” or “Such delicious cake, what a bind!” and laugh uproariously like a shameless winner.

A third way to reject the humblebrag is to challenge the humblebraggery of others with kindness, wit and sincerity. When faced with “Oh no, I have so much work to do,” your cheerful response should be “Don’t worry, you’ll get through it bit-by-bit,” and perhaps recommend Getting Things Done by David Allen to help with their problem. Too much work, you say, is a problem, not a cause for celebration. Too much work is a failure in personal (or personnel) management, not a worthwhile status symbol. When faced with “Oh phew, I did so much work today,” I recommend the phrase, “What do you want? A medal for shovelling shit uphill?” or, the kinder “Good for you. You should take tomorrow off.”

The point of all this, remember, is to stand up to the Protestant Work Ethic. We want to challenge the idea that overwork and tasteless consumerism are status symbols, and to promote the idea that if anything is worthy of being status symbols it should be leisure, pleasure, and an abundance of time.

Escape the humblebrag! Flee to the honest boast!

★ This essay was made possible by Drew Gagne, Daniel Gutierrez, Susan Boulden, William Staszewski and 51 other intelligent and good-looking patrons. Tell others!

Hannah’s Escape

I’ve been reading some Hannah Arendt and already I’m smitten.

I recommend reading her work (especially now — she wrote about fascist totalitarianism) but all I wanted to mention today is the glorious way Arendt and some others escaped the Nazis during the war. Get this:

There was a family who had a house with a front door in Germany and a back door in Czechoslovakia. They’d invite people over for dinner and let them leave through the back door at night.

I wish I had a house like that, perhaps embedded in Hadrian’s Wall. Might apply for art council funding.

Essentialism

This is nifty. It’s from Essentialism by Greg McKeown.

50 Hoped-For Escapes

I once mentioned a website called 43things. It doesn’t exist any more but I wrote a note of something I found there. (Update: the site is back!)

43things was a social network about personal ambitions. You’d enter your dreams and goals and other people could cheer you on. When successful, you could write a little post about how you did it and whether it was worth it.

I mainly used it to eavesdrop on other people’s life plans.

I once popped the word ‘escape’ into the in-site search engine and came up with some 472 items. The result was like a measure of gross international unhappiness. Or at least dissatisfaction. Or, more positively, a measure of people’s desire to put things right in their lives.

Many of the ‘escape’ ambitions are either similar to other ones or don’t make sense, so I’ve boiled them down to a single report of 65 hopes for escape. It’s almost like a poem, composed by the Citizens of the Internet, circa 2013:

Escape the masses

Escape from Google

Escape into nowhere

Escape my past

Escape from this city/country

Escape the cubicle

Escape America

Escape from Alcatraz

escape death

escape reality

escape society

escape capitalism

Escape my parents

Escape From Jail

Escape materialism

escape Suburbia

escape from it all

Escape escapism

Escape…(for a while)

escape from myself

escape to a rainforest

Escape solitude

Escape from Zajecar for a while

escape from my life

escape winter

escape poverty

escape by train

Escape Debt

escape depression

Escape England!

escape the office

escape the routine

escape the midwest

escape the “curse”

escape from my ego

escape Nottingham

escape to paradise

escape plastic

Escape from Shawshank

Escape religion

Escape Ireland!

Escape from Iran

escape from LA

escape tradition

escape everything

escape from intolerance

Escape anxiety

escape from the matrix

escape to scotland

escape a life of corporate servitude

Pssh, I could tell you how to do any one of those.

The Mysticism of Work

Found in a zine by Amy Peltz, a quotation from Simone Weil:

Why has there never been a mystic, peasant or worker to write on the use to be made of disgust for work? Our souls fly from this disgust and try to hide it from themselves by reacting vegetatively. There is a mortal danger in admitting it to ourselves. This is the source of the falsehood peculiar to the working classes.

There has now, Ms Weil. It’s New Escapologist!

Of Design and Destiny

Must modern cities be ugly? Of course not, and they are not. But I walk past this “Skypark” thing quite often and it’s horrible. I mean, look at it.

It stores a few hundred teleworkers between 8am and 8pm, which is an act of evil in itself, but must it look like one? I’m only a passerby — I don’t deserve to be insulted.

“Know your place,” that building says, “You’re a cog in a machine in a grey, grey world.”

I like to wear a colourful pocket square when I know I’m due to pass it. It’s on a street corner with a lot of traffic, so I sometimes play with my yo-yo while waiting to cross.

“Such frivolousness,” the building says, “Earn your pittance! The grave is your destiny, so get trudging!”

Everyone likes the idea of beauty but we’re increaingly turning our backs on it because of some vague notion about the importance of professionalism and seriousness. To be beautiful is to be eccentric or profligate.

Design today must apparently be hard-edged, sober, practical, sturdy, and — while actually very expensive — look cheap. That, or it can be beautiful and temporary and safely stashed in a museum where nobody will see it.

To add a little flourish or some colour or nuance — or even to spell something properly — is seen as increasingly anachronistic.

I’m always cheered to see a red telephone kiosk. It’s a design classic, it works, it’s an internationally-adored symbol of Britain. It’s cheap to use, it’s practically indestructible, and it can be trusted to deliver. Most of us would love to have one on our street corner, but we can’t apparently.

BT started getting rid of the red telephone box in about 1985, planting those horrible black perspex ones instead. You just know this was the result of a meeting in which some influential philistine said “the classic red telephone box does not reflect BT’s corporate values.”

The new kiosks said everything about municipal mediocrity. “Don’t go thinking you’re part of an empire,” it said, “don’t go thinking you’ve got better things to do than go to school and get a job and die.”

I mean, look at that one in the middle. They were routinely vadalised but how could they not be? I’d love to smash that one in. It’s practically what they’re for. In response to this public disdain and an outspoken nostalgia for the classic red box, BT brought out a happy medium which looked a bit like the shitty modern ones but with a domed top reminiscent of the classic.

The message was “Yes, everyone likes the classic… but we can’t have it because of the way the world is going. Nobody likes the modern version, but we have to have it this way. Haven’t you heard of inevitable decline? You have to work pretty hard to fulfill a thing like that.”

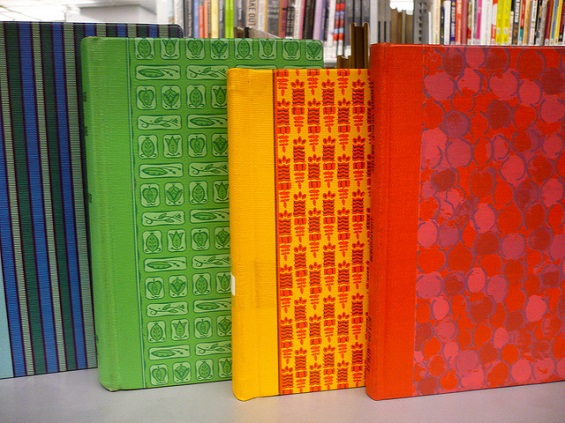

I once visited the Central Public Library in Seattle — a great building designed by Rem Koolhaas — and saw many beautifully-bound books inside. A one-time librarian, I knew the story of these books just by looking at them. The library once had its own bindery in which many old books were carefully rebound to extend their lives. Beautiful materials were chosen to bind the books so they’d be pleasing to the eye. The bindery was closed circa 2002 “because that’s not how things are done today”.

The present day is about Kobo and iPads, not beautiful, free-to-borrow books no matter how much we like the idea and how much sense it makes. Imagine a world in which people carried these books around the city instead of e-readers. It would be beautiful but we can’t have it because of an imaginary landscape called “the way the world is now.”

It’s a destructive logic causing good ideas to be stifled at birth or else scrapped after decades of flawless service. All because of cultural pessimism. It’s as if our national and international misery is seeping upwards into our design.

The implication is that we live in a time of austerity, utility, uniformity, corporate values, plasticity, disposability. Our period cannot be allowed to be one of domesticity, prettiness, happiness, dignity, peace, quiet or luxury.

The idea is that everything is doomed. It suggests there’s no alternative, that ugliness is inevitable, and that the destiny of all material — including human brainstuff — is to contribute to this harsh and sober vision.

But it’s not destiny. It’s all unnecessary. Britain and America are among the richest countries in the world. We’re producing more artists and designers than ever before. The world doesn’t need to be about the bottom line. Bladerunner was a warning, not a blueprint, yet look at the state of the London skyline: symbolic of little but graceless corporate guzzling. “Skypark,” meanwhile, sounds like something from Terminator 2: Judgement Day, a world where robots are in charge and love is on the scrap heap.

It doesn’t have to be this way, my pretties. Design your own lives. Act, move, earn, and speak beautifully. The others will join in sooner or later. Act as if you lived in the early days of a more beautiful world.

Let’s Not Give Them an Inch

Remember Chiune Sugihara? He was the Japanese diplomat in Lithuania who, during World War II, went over his bosses’ heads by issuing exit visas to thousands of Jews whose lives were threatened by the Nazis.

We posted about him at New Escapologist because he used his free agency where others would have denied it. He was a cog in a machine but he refused to act like one.

I don’t think it’s fanciful to say that many of us will be given the opportunity over the next few weeks, months and years to act as Chiune Sugihara did. Some have already risen to the occasion.

Challenge racism wherever it arises. We too often tolerate intolerance.

Never play devil’s advocate by saying “well, at least the actions of Trump/May/Farage/White Supremacists will give us [blank].” Don’t look for silver linings in blatantly unconscionable acts. No potential gain is worth what they’re doing.

Do not look to their followers and confuse their cowardice, ignorance and spite with an appetite for change.

Do not pull your punches. Do not give them an inch. They’ve already taken their mile.

Whenever you get a chance — and you will get chances — use it to do the right thing. Your opportunity may not come in the form of saving six thousand lives with a signature, but you should still look out for that fork in the road where you can grind like a cog or step up like Sugihara.

Expletive Deleted!

I’ll probably not post much more about Universal Basic Income to this blog (though I reserve the right to tweet about it) lest NE become too one-note while there’s so much going on with UBI. As this article puts it:

There has recently been a surge of interest in basic income. […] Long derided as unaffordable and conducive to idleness, basic income is now attracting support from many quarters and standard objections have been robustly challenged. This interest has prompted the launch of several basic income pilots around the world. One started on 1 January in Finland with others planned in Ontario, Canada, Oakland, California, Aquitaine and Catalonia, and discussions are ongoing in Fife and Glasgow. A US NGO, GiveDirectly, is raising $30m for a 12-year experiment in Kenya.

But before we go quiet on this front, let me tell you that Utopia for Realists is a rather good book. It’s light on ideology and instead draws on a wealth of facts and figures, projections and dispassionate analyses of trials. We need more of this, especially in the age of personality politics and post-truth awfulness. There’s a great chapter about the history of UBI in which I learned the following.

President Nixon (of all people and, hey, as of this week he’ll only be the third most-despised US president in history) tried to get UBI for America. It was during a swell of national ambition after the moon landing, and in response to an open letter signed by 1,200 economists supportive of UBI.

Trials were conducted and the Nixon administration came tantalizingly close to eradicating poverty in America. Alas, it never made it through the Senate.

Attempts to save the project were made for a number of years and, in 1978, it almost made it. What ultimately killed the project was a moral panic resulting from a particular statistic from the trials: a 50% increase in divorce rates. This happened, it was reasoned, because women in receipt of UBI no longer had to stay married to jerks just to have food and a home.

Too much freedom for women was the concern that canned UBI in America.

I’m not sure which is more appalling — the very fact of this concern (“I’m not ironing my own goddam babies!”) or (wait for it) the discovery in 1988 that the 50% divorce figure was the result of a statistical error.

This is probably how the world will end, isn’t it? Stinking moral judgement based on obsolete ideas and a made-up a fact.

It resembles, to my mind, the current objection that UBI would lead to idleness when (a) trials indicate that it won’t, and (b) morally, there’s nothing wrong with idleness anyway. People shouldn’t have to stay put in a kitchen — domestically or professionally — if they don’t want to.

If you want to get a taste of this book before buying it, here is its author, Rutger Bregman, speaking quite compellingly on CBC Radio.

An Escapologist’s Diary. Part 49. 2016 Review.

Yes, folks, it’s time for the traditionally belated end-of-year review and report to my imaginary shareholders.

This year, the review’s late because I kept making the mistake of writing how I feel about Trump and Brexit and then deleting it. You can probably imagine those feelings because they’re obvious and shared by many. Instead, let’s stay positive and have a pleasant time before we’re all killed by a nuke or in a pogrom. (Haha. I am funny.)

Ahem.

My lovely partner and I finally live in Hyndland, in accordance with our obvious destiny. We were successful in securing a visa to live togther in my country of birth thanks to some decent people at the immigration department and having met the evil financial requirement through part-time toil.

Escape Everything! came out in January, which became the main event of my year. I mean, I got a book out of my brain and into the world – how great is that? Very!

We sold the rights to the German market, resulting in a chunky translated edition called Ich Bin Raus. It seems to be selling well in Europe and, by my standards, getting a lot of attention. This has resulted in a million Germans seeing a picture of my face before slinging it into the papierkorb.

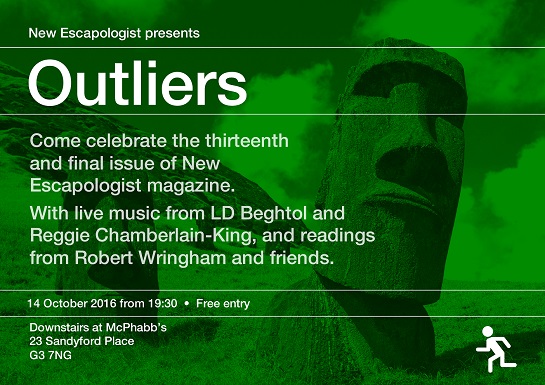

2016 saw the release of New Escapologist Issue 12 with Will Self and a lot of nice articles about walking. Later, we launched Issue 13 with Caitlin Doughty and a very fine launch party.

I knew long in advance that Thirteen would be our final edition, though I didn’t know what the magazine’s afterlife would be like, if any. In the event, I decided to continue the blog you’re reading now, to spruce up the website, and to continue my Escapology column in the Idler – the first four installments of which were printed in 2016.

I helped edit Luke Rhinehart’s novel, Invasion, all the while wishing I could tell my 18-year-old self that he’d grow up to work a little bit with The Dice Man. The book came out in August and if you pick up a copy, you’ll see my name on the back cover, championing what lies within as if I weren’t personally involved in it.

We launched a new essay series under the auspices of New Escapologist, which will hopefully be funded through Patreon. We’re half way to having enough people to make this happen and keep the whole enterprise alive, post-magazine, so if you’ve enjoyed the website in 2016 or for the previous nine years and think it’s worth a quid a month, please join the New Escapologist green berets.

Friendships have been renewed and strengthened, good habits have been cultivated, and we indulged in some travel, twice to Montreal and twice to Berlin. They were all good trips but we really should spend our 2017 travel budget on going somewhere new. There was also that weekend in Wales for the Stewart Lee-curated festival, at which I looked like this:

— Robert Wringham (@rubberwringham) April 21, 2016

I ate lunch, fought eczema, watched cartoons, did a tiny bit of comedy on the night Gary Shandling died, sold books with Simon Munnery at the Edinburgh festival, aced the pub quiz, fucked the pub quiz, posted the first in a trilogy of deliberately boring podcasts, sat on my arse reading quite a lot, and solved my sock problem.

In 2017, I’d like to write a novel, start a second Escapology book, post twelve essays for the Patreon gang (here’s that link again), and maybe write and perform a one-person show for August. Not much then. Tune in this time next year to see which of these projects thrive and which ones die in a ditch!

Thank you to everyone who stuck around this year, read the books, and supported the Patreon. I need you and I’m grateful.

The @PenguinUKBooks website says my book weighs 395g. I wrote those grams. #soemotionalrightnnow https://t.co/VwP9mD7hGm

— Robert Wringham (@rubberwringham) January 22, 2016

★ The post-print phase of New Escapologist is just beginning. Go here to join in.

★ You can also buy all thirteen issues in print or PDF (in newly discounted £20 bargain bundles) at the shop.