Going Out the Door One Day and Never Coming Back

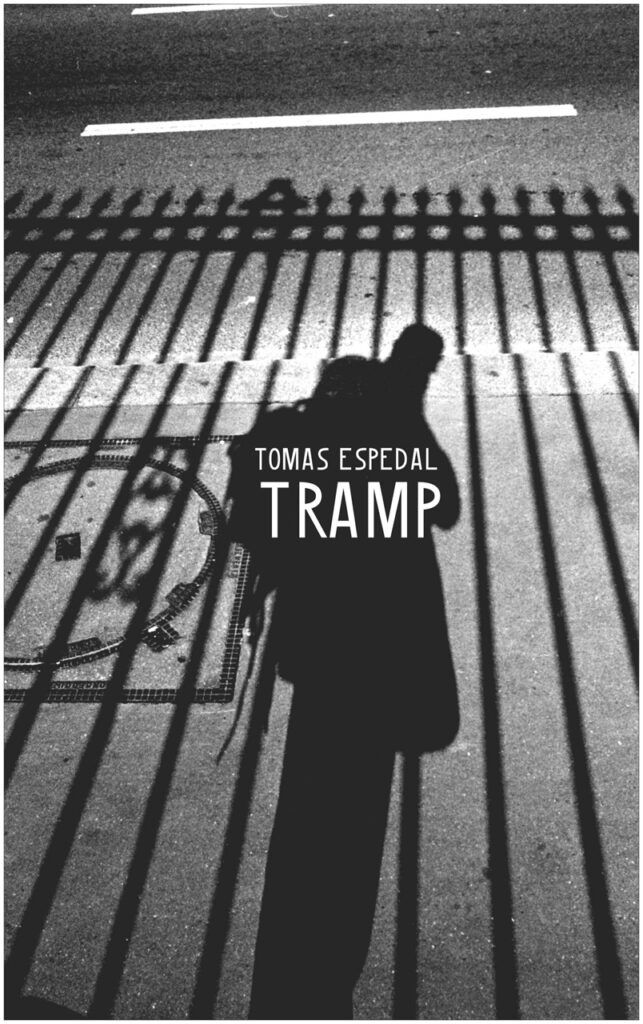

Thank you to the New Escapologist reader who put me onto Tramp (2006) by Thomas Espedal. It’s an excellent book. Not quite a novel, not quite a travellogue, it flies by like poetry.

Espedal doesn’t want to settle down:

I’d never been fond of houses, they were too large and unaccomodating. A house is demanding, difficult. One must learn to master a house. One must learn to dwell.

… superfluous rooms, the hostile furniture, this semi-temperate interior that speaks to us of our wasted work, our misused moneys, our dull lives.

He just wants to escape:

The Dream of Vanishing. Disappearing. Going out the door one day and never coming back.

He wants to keep on walking:

The wanderer is, according to Rousseau, a plain, peaceful man. He is free. He has left the city, he has left his family and obligations. He has said farewell work. Farewell to responsibility. Farewell to money. He has said goodbye to his friends and his love, to ambition and future. He is really a rebel, but now he has bidden farewell to his rebellion as well. He wanders alone in the forest, a vagrant.

Or gliding along by rail:

I like sitting on a train looking out of the window; seeing the landscape roll past while I tentatively read a novel: Vaksdal, Trengereid, Dale, Evanger, Voss, and the first snow, the first frost, the first kiss in the snow on the frozen stone wall down by the lake shore at Vangsvatnet; winter, summer, spring, and the train rolls past.

These are just some choice quotes that reflect our (or maybe just my) tendencies here at New Escapologist. Espedal likes other things too, such as mountaineering and driving fast cars. He’s just a guy who loves life. This comes over on the page, but quietly and elegantly so. What a great book.

Also noteworthy: Espedal walks (and climbs mountains) not in sportswear… but in a suit!

*

Sympathy with the vagrant? Issue 16: Footloose and Fancy-Free is your companion. Prefer to stay put? Issue 17: All the Way Home is yours. Open minded? Get both!

A Postcard From Monterey, c1955

It was a maximum-security prison. There was just no easy way out of it.

This guy isn’t talking about Manus Island. He’s talking about midcentury American suburban life.

After years of being “a model citizen,” he says, he dropped out and went to Monteray, a centre of counterculture, within proximity to the ocean.

And all the while I knew I had put the bars there. I’d been constructing this thing since the time I was a child.

Thanks to readers Lauren and Joe for sending this in. (It has nothing to do with LSD, by the way. The title is clickbait but it’s a lovely video).

You Call Jim Webster

Friend Reggie draws our attention to this 1995 letter from John le Carré to Stephen Fry. Fry had suffered a breakdown and done a bunk while performing in a West End play called Cell Mates. In sympathy, John le Carré writes:

if you’re in the escaping business, here’s what you do: you call Jim Webster, boat broker, in Fort Lauderdale, you charter a small motor yacht with crew out of Nassau, and you cruise the remote islands of the Exumas for 2 weeks at unbelievable cost and you will have escaped as never before. You take friends if you need them, speak or don’t speak to the crew, anchor in empty bays rather than marinas, and you escape all mankind.

So that, says Reggie, is how the other half escape. Blimey.

le Carré goes on to recommend certain places in Germany conducive to going to ground. I’m not sure why Germany, as Fry scarpered to Bruges in Belgium, but among the places he likes is Freiberg (“lots of dotty families hidden in the hills”), which is where I went to interview Jonathan of Analog Sea for our Issue 15. I can confirm it’s a beautiful place to hide. He also mentions access to libraries, which I agree are useful facilities to consider when plotting an escape: never go where books aren’t.

He goes on to give his credentials as an escape artist, “speaking as an artist in this field, albeit a failed one:”

I completely relate to your duckdive … I escaped from Sherborne to Berne (at 16), dived into a monestary in order to escape marriage, escaped to the spooks, escaped the spooks to writing, nearly at times escaped writing for the ultimate escape, and now I’m 63 so who gives a fuck anyway?

The he ends the letter with:

PS: fuck them all.

Quite right.

*

An Escapologist’s Diary: Part 81. Crash.

As you know, dear diary, I am on sabbatical. I’m taking it easy for six months as a restorative measure following a busy 2024. How, you might ask, is it going?

He Imagined Knocking the Whole Thing Down

Here’s a moment from Owlish by Dorothy Tse.

It’s a slightly creepy novel about an ageing university professor who falls in love with a life-sized music box ballerina. He goes AWOL from his depressing work and domestic lives to embark on what he sees as his last chance of adventure.

He moves into an old church on an uninhabited island, fills it with the beautiful art objects formerly boxed up in his study, writes poetry, hangs out with his doll thing, and scowls at his old workplace from a distance:

The less he went into the university, the better Professor Q felt. His mind was clearer and he felt ten years younger. He narrowed his eyes and extended his right thumb, trying to blot out the distant office building. He imagined knocking the whole thing down

He turned back to face the university and thought of himself sitting behind one of those windows, day in, day out, working like an automaton, and suddenly felt absolutely furious.

I’d say it’s amazing to find so many bloggable anti-work quotations in the books I read, when all I’m doing is trying to do is kick back and relax. But the hatred of being told what to do is all encompassing. It’s everywhere. Maybe it’s not taboo at all.

*

New Escapologist 17 is back in print for a limited time only. Baby, you know what to do.

Issue 17 is Back in Stock

New Escapologist Issue 17 is back in stock. Get your copy from the shop today, while limited stocks last. Perhaps also along with an Issue 16 or a Good Life for Wage Slaves book?

Pre-ordered copies are shipping now. Thanks to everyone who did. 🙂

I sometimes wonder if newer readers, especially those who found us by Substack, think that our print editions contain the same content as the blog and/or newsletter. They don’t! The content of our magazine is unique, high-quality material and represents our best work. The blog and newsletter are elevated marketing tools for the magazine. The real McCoy is only available in print (and epub). Enjoy!

Bring Up Irrelevant Issues as Frequently as Possible

“The World War II-era Simple Sabotage Field Manual is full of steps that office workers can take to resist leadership,” writes Jason Kobbler at 404.

Declassified by the CIA in 2008, it’s a handy booklet explaining how workers can resist Fascism in Europe.

404‘s point is that it can be used now to resist Trump and Musk in the US and, given that it’s going viral at the moment, it probably is.

What strikes me, however, is how the obfuscation techniqes are the same as ones deployed by leadership against workers who actually and perhaps insanely want to get things done. As a white-collar functionary who sometimes wanted to fix or improve things, I was constantly skuppered by this sort of bullshit. As such, I suppose, at least I know it works.

*

New Escapologist Issue 17 is back in print! Get your copy here.

After That Day, I Stopped Worrying

I’m reading Sea State by Tabitha Lasley.

It looked journalistic when I picked it up — plastered with glowing and collegial-looking praise from the Irish Times and Financial Times and the Observer — and supposedly based on interviews with offshore oil riggers.

In fact, it’s the memoir of an extramarital affair, which makes all that praise look a bit selacious.

It is good though! Inciteful and well-written. It’s another citation toward my evolving theory that the point of reading is a form of psychonautics; to travel in the experiences of others, whatever they might be.

It’s also Escapological. Lasley quit her job in journalism, dumped her crap boyfriend, and abandoned London in favour of becoming “a writer without portfolio” in chilly Aberdeen.

On her quit:

When I gave my notice in at work, my editor told me she’d miss me, then had a long conversation with another editor, over the top of my head, about the unlikelihood of attracting a decent replacement, given my simean day rate. Up until that point, I’d thought walking out of a job might be one of those decisions I’d come to regret. After that day, I stopped worrying.

On starting over:

I went to Morrison’s [supermarket] on King Street for a knife and chopping board, and had a sudden sense of what I must look like to the other customers. A whey-faced woman in her thirties, spending Saturday night alone, buying kitchen utensils cheap enough to shame a student. A battered wife. An asylum seeker. Witness to some violent crime, relocated by the govermnent, her new address designated by alghorithm.

On a darker flavour of walking away:

Married men never leave their wives. And yet, I always knew he would. I had a sense that if I led by example, if I left my job and the city where I lived, if I showed him how easy it was to walk away from things, he would follow. I was shocked and unsurprised at the same time.

*

Narrow Escape

This couple have lived on a narrowboat for one year. Well, it’s more like a year and half now because I was late to the vid.

Anyway, here is their first annual report. It contains some more information about my favourite boating term, continuous cruising.

Also, look! A boat named “Narrow Escape!”

*

New Escapologist Issue 17 is being re-printed. Shipping on or around Feb 10th. Get yours here today.

The Escape of Jo Nemeth

Jo Nemeth lives without money in Australia. Like Friend Henry, she was inspired by Mark Boyle, a New Escapologist favourite.

For the first three years, Nemeth lived on a friend’s farm, where she built a small shack from discarded building materials before doing some housesitting and living off-grid for a year in a “little blue wagon” in another friend’s back yard. Then, in 2018, she moved into [a friend’s] house full-time; it’s now a multigenerational [multi-family] home.

Instead of paying rent, Nemeth cooks, cleans, manages the veggie garden and makes items such as soap, washing powder and fermented foods to save the household money and reduce its environmental footprint. And she couldn’t be happier.

“I love being at home and I love the challenge of meeting our needs without money – it’s like a game.”

In an early blog post, Jo describes her big life change as “an exit strategy” and places it in the context of social action:

Every day I am thinking about my exit strategy. My fossil fuel exit plan.

Sure, fighting for system change on the streets and in parliaments must be part of our strategy, but it can’t be (won’t be) everything. After all, the system that needs changing is a destructive, violent machine of which we are all cogs. Maybe system change will come just as quickly from, or at least be aided by, many of us putting into place our household exit strategies. It will definitely play a part. It has to. We can’t go getting arrested on the streets to get emissions down then fly home, jump in our cars and go cook the evening meal on the gas stove. Who’s going to take us seriously?

Jo is now moving out of the house to get back to basics again:

she’s currently using recycled building materials to fix up a cubby in the back yard where she plans to sleep and spend her evenings reading by candlelight. “It’s very small, just big enough for a single bed and some standing room. There’s no electricity or running water.

“But I want to feel more connected to reality, to the birds and the stars and the sun and the rain. I feel really disconnected living in a big house. We just had a full moon and I almost missed it!”

I like how she describes a tiny home in the natural world as “reality.” Because of course it is! It’s the same point made by this brilliant woman, who describes “the real world” of suburbs and cities and the internet as “the madness.”

Many people who read Jo’s story probably see things the other way around: that they’re the ones living in reality (a consructed and networked world upheld by a majority) while Jo lives in a bubble of fantasy (an impractical romance). Yet she proves, again, that escape to an outlier reality where personal values prevail is entirely possible.

*

The reprint of New Escapologist Issue 17 is about to go to the printers. Get your copy here.