The Lost Art of Declining Politely

Ours is the magazine of “getting out of things.” We tend to focus on big things like jobs, but I sometimes think about adjusting the microscope to talk about escaping micro-commitments like parties you don’t want to go to.

I usually bin this idea because, really, it comes down to: just say no — politely.

An item in today’s Guardian confirms this decision but also made me think a little further about why so many of us have trouble saying no.

Maybe it’s because you don’t want to damage a relationship. But if a relationship is so fragile that it could break when you don’t want to go dancing, is it really a relationship worth preserving at such costs?

Maybe the fear of saying no is to save your own reputation. You don’t want to be seen as a bad sport or a wrecker or no fun. Not going to the party would be bad press for yourself.

I think the real reason, however, is a sort of projection. It’s our own fear of rejection (combined with decent human empathy) that is to blame. Because we don’t like be rejected, we couldn’t possibly reject another.

So that’s where the work needs to happen. If you don’t like to say no, you might need to work on your own fears.

At the risk of being mildly indiscrete, I think I learned the art of saying “no” from our own Tom Hodgkinson. When he asked me to write a column for the Idler in 2016, I giddily sent him my first try. “This is not what I had in mind,” he said, “This is more of a diary piece.” He explained what he was looking for and I got on with it.

It wasn’t the answer I wanted but at no point did I question Tom’s authority (or natural right) to say no. Since then, I’ve not struggled to reject New Escapologist submissions I didn’t care for. And when I politely declined an early cover design for Stern Plastic Owl, the designer thanked me for my clarity and we got on with doing the right thing instead.

That Guardian article does not encourage people to decline honestly or politely: it encourages us to wuss out and to tell white lies. This comes at a cost to our character and it disrespects people.

One of the things people struggle with, for example, is saying no to charity workers on the street. The article suggests we tell them that we already donate to another charity so as to “validate their cause and therefore their endeavour.” They know you might be lying, apparently, “but they also know why, so the exchange ends up being quite pleasant.”

I think not. Just because you’re afraid of rejection doesn’t mean they are. Respect them by being honest. Don’t waste their time. Let them go free to find success with a less stingy pedestrian. Here’s how to handle a chugger: don’t break your stride, smile kindly, and (at most) say “no thanks, sorry.” But always smiling. And always walking.

The same goes, basically, for any other request you don’t want to indulge. Decline politely, with clarity and honesty, and don’t stop.

*

Find more wisdom on getting out of things in New Escapologist Issue 15 (due this week!)

Hostile Environment

Yesterday, my partner got her certificate of citizenship. She took an oath of allegiance and we stood for the National Anthem without laughing. We had our picture taken with a portrait of the Queen (the new one of Charlie, they said, was still in the post).

There was a sense of pissed-off solidarity among the twenty or so new Brits in the room. The officer of ceremonies tried to make it all sound positive and almost like a registry office wedding but we were all at the end of a long and tiring journey. One couple in particular looked downright furious. To this couple I tried to telegraph a message: “Don’t fuck it up now. Not at the final hurdle.”

Anyway, we made it. Phew! And not a moment too soon, it seems. A remark that will make sense in a minute.

For anyone angered by (or curious about) the “hostile environment for immigrants” I struggled to write about in The Good Life for Wage Slaves, the political writer Ian Dunt explains it well:

In 2012, as part of the Hostile Environment policy, Theresa May set a minimum income level for British citizens to be allowed to bring their foreign wife or husband to the UK. There was no need for it. People on spousal visas are not entitled to claim welfare and most of them have to pay the NHS surcharge on application. But May, despite her recent rehabilitation as some kind of imaginary liberal haunting the conscience of her former self, was in fact a deeply authoritarian and mean-spirited home secretary, so she did it anyway.

The minimum income requirement was set at £18,600. That might not sound high, but it is. People who work part-time in retail or hospitality – often women raising a child – don’t reach it. But even where someone could satisfy the threshold, it frequently hit them as a sequencing problem. They’d meet their partner when they were living in another country, fall in love, settle down, get married, maybe have a kid. Then, one day, they’d decide they wanted to come home. And that’s where the problems started.

This minimum income requirement was precisely what made it difficult for me to come home with my wife. I didn’t have that sort of income as a self-employed writer so we had to get jobs we despised with good reason and to keep them for almost three years.

We couldn’t quit those jobs for fear of de-facto deportation, a fear that lingered over us for years. We couldn’t lose them either, which made it difficult to refuse to do certain things at work or try to negotiate better conditions. Thousands of people are still in this trap.

Usually they would have no idea what was happening. Most had never heard of the spousal visa requirements. It was typically beyond their moral comprehension that the government would put obstacles like this in front of their family life. They assumed, on some deep instinctive level, that being able to live with your husband or wife was a core individual right as a British citizen.

That was us. We had no idea what was happening because it wasn’t happening when we began our relationship. We met in 2008, moved in together in Canada, and decided (hah!) to come back to my country together in 2015. Theresa May’s new rules were put in place in 2012.

Now brace yourself for an update. The £18,600 income requirement that gave us so much trouble and didn’t exist until 2012 was raised this week to an astonishing £38,700:

This is higher than the average and the mean income in the UK. It’s unachievable for around three quarters of British citizens. [Most nurses, for example] do not earn anything like that much. They’ll be barred from living with a foreign partner. Many teachers do not earn anything like that much. They’ll be barred from living with a foreign partner.

And it’s all in service of what exactly?

It makes no sense. Inward migration last year was 1.2 million. The total number of visas in this category was 65,000. Even if the move eradicated them all, it would barely dent the numbers. No voter is going to give [current Prime Minister] Rishi Sunak credit for knocking 50,000 off the overall figure. But for the sake of the impossibly small chance that one does, he is mutilating the lives of British citizens.

Ian’s piece goes on to describe the material and emotional effects this has on families, caused entirely, he points out, by a political party so enamoured of “family values.”

It may not effect you personally (and I sure wish I didn’t have to sully myself by reading about these horrors) but if you’re interested in the Hostile Environment (which, lest we forget, is no media slur but the original official name of the project), it’s worth reading Ian’s piece in its entirety.

As an Escapologist, you probably believe in free movement up to a point. I believe in open borders (read the case for it in the relevant chapter of this book if you’re not sure about that one) but nobody in politics is suggesting anything remotely that radical at present: perfectly ordinary middle-class people who met their partners abroad just want to come home without it ruining their lives is all. And the request is being cruelly, brutally, authoritatively denied.

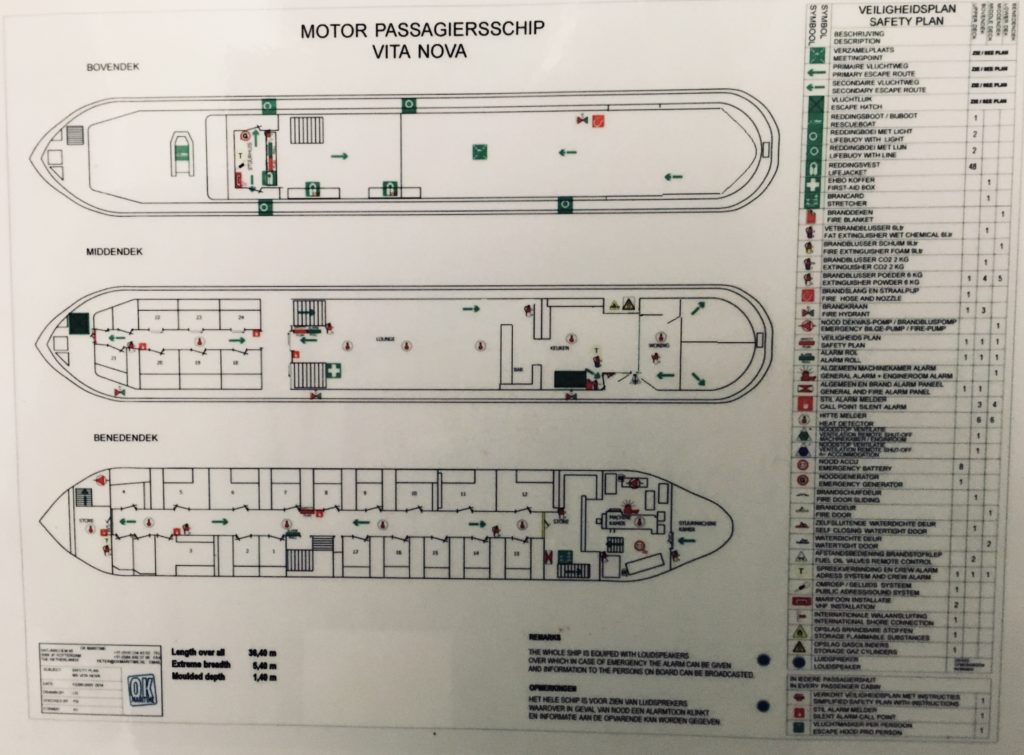

An Escapologist’s Diary: Part 75. Boat!

As part of my ongoing hostelling adventure, I slept on a boat!

We’re looking at existenzminimum again:

You get a private cabin (privacy being a plus in hostels) reminiscent of the cabin you get on a sleeper train or an overnight ferry.

Since the boat is on an Amsterdam canal rather than a life on the ocean waves, you feel no watery motion while sleeping at all.

But if you open a curtain in the dead of night… you might see a duck. 🦆

*

There’s a little more about the minimalism of hostels in Issue 15.

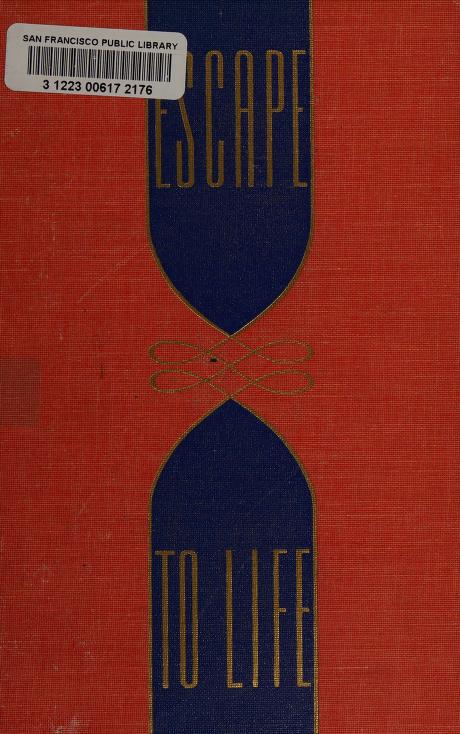

Escape to Life

A beautiful cover of a rare book: Escape to Life by Erika and Klaus Mann. The book profiles the artists and intellectuals who escaped Nazi Germany to live elsewhere in Europe and America. The ticklish sense of justified flight is deeply exciting.

The book can be found easily in German, which is fair enough because it’s a German book BUT it was first published in English and when parts of the original draft were destroyed the English version was used to recreate the lost content. It’s a shame that it should be out of print now.

I don’t have £130+ to buy a copy from AbeBooks but the Internet Archive has a scanned library copy, which, mercifully, can be read online.

Eccentrics

This is from Wendy Carlos, genius musical composer:

The greatest thing we’ve got going in our culture is our eccentrics. I was once embarrassed by my eccentricities but now I value them.

In other words, be different. Don’t be afraid. To plough your own furrow benefits not just yourself, but the whole world. To stand apart is not to turn your back on society. You’re at least the control group, at best the great experiment.

In the spirit of this quotation, New Escapologist Issue 15 is subtitled Experiments in Living. Our eccentric spirit animals are, if not Carlos herself, Edward Carpenter (addressed), John Stuart Mill (channelled), and Ariel Anderssen (interviewed).

Give My Child an Ikea Desk and Twelve Hours a Day of Sedentary Typing

Thanks to reader N for sharing this passage from Dave Eggers’ Heroes of the Frontier.

It’s nominally about parenting but really it’s about how to spend a good life versus the violence of social expectation:

She began to conceive a new theory of parenting, where the goal was not the achieving of a desired result. The object is not to raise a child for some future outcome, no! Times like these, together in the pines amid the fading light, as the kids run through the long grass, her son gravely teaching himself archery while her daughter tries to induce some self-injury, these moments alone were the object. Josie felt, fleetingly, that she could die having achieved such a day. Get to a place like this, get to a moment like this, and that alone is the object. Or it could be the object. A new way of thinking. Stretch some of these days together and that’s all one could want or expect. Raising children was not about perfecting them or preparing them for job placement. What a hollow goal! Twenty-two years of struggle for what – your child sits inside at an Ikea table staring into a screen while outside the sky changes, the sun rises and falls, hawks float like zeppelins. This was the common criminal pursuit of all contemporary humankind. Give my child an Ikea desk and twelve hours a day of sedentary typing. This will mean success for me, them, our family, our lineage. She would not pursue this. She would not subject her children to this. They would not seek these specious things, no. It was only about making them loved in a moment in the sun.

*

The Stack

I was on The Stack recently, a podcast about magazines from Monocle Radio.

Host Fernando is a lovely and attentive guy and I think I did quite well thanks to his questions. I explained New Escapologist accurately and with good humour as well as explaining the appeal of a less work-driven lifestyle. I also had a cold at the time, so my answers are all baritone and vocal-fried. Enjoy!

The whole episode (and indeed the show) is worth a listen but the bit about New Escapologist starts at 8:34.

*

Get your hands on the print edition we’re talking about here.

Out of the Mouth of Babes

Thanks to Reader S for sharing this.

The YouTuber talks about economics and the stock market, but I like the way she defends the younger woman who complains about the reality of full-time work:

Clearly in a state of distress, the younger woman laments:

I know I’m probably being so dramatic and annoying but this is my first job, like, my first 9-5 job after college and I’m [working] in person and I’m commuting in the city and it takes me fucking forever to get there.

She explains how she can’t afford to live closer to work because city rents are so high, how she doesn’t have time to cook properly or work out or be with friends or find a partner, how it’s all just too much.

Predictably a lot of people in the comments call her a whiner, that she’s spoiled, that Gen Z are lazy, and “welcome to the world”-type refrains.

But… she’s right! She’s absolutely right to be distressed about the demands suddenly placed in her lap by the 9-5. And she’s right to be dismayed that this is considered normal, is the best system we’ve come to as a society. Only a liar or a moron (or, of course, a beneficiary) would disagree. And given the state of the economy (by which I mainly mean the housing and cost of living crises) it’s truer than ever. It’s her generation who should be complaining the loudest.

The economics YouTuber says:

This is a very common experience. When you join the workforce you end up feeling all of these things this girl is talking about. It’s a completely reasonable response to overwhelming stressors.

Which is obviously correct. She goes on to talk about the labour movement and all sorts of interesting things, so it’s worth a watch. But I really just wanted to say how impressed I am that Gen Z can see through the bullshit so easily and that there are fellow dissenting voices willing act in solidarity, calling this bullshit situation out.

What the Gen Z girl doesn’t say is how she’s supposed to be grateful for this lot as well, that she’s supposed to be the grateful inheritor of a clean and easy-going technocracy. She’s not aloud to be unhappy, not allowed to work grudgingly. As we all know, that sort of daily masking is exhausting.

*

Tired of the everyday grind? We offer you escape! New Escapologist Issue 14 is available now.

Continuous Cruisers

This is from a nice piece by writer Faye Keegan about escaping the toxic rental market to live modestly on a narrowboat.

We scraped together what savings we had, took out multiple loans and eventually managed to secure a boat mortgage (they’re a thing), before finally buying our narrowboat in July 2021. We spent the summer doing her up: I learned to tile and managed to figure out the plumbing, Nige laid down new pallet-wood floors, and my mum helped us paint. In September, we moved aboard full-time. Our daughter was born the following August.

This is something I think about a lot. We reluctantly escaped the rental market too and it required a similar sort of pairing down. We lost our spare room and had to move to a less lovely part of town.

If you’re renting and are appalled by how much rents have shot up and if you have any chance of escaping, you should definitely think about ownership if you can find a way. It pains me to sound so much Hilaire Belloc though: it doesn’t agree with my politics and I always liked renting. But needs must as the devil drives his landlordly gold-plated sports car over your face.

Whenever I’ve look into house boats as a happy alternative to bricks-and-mortar ownership, the mooring (i.e. the parking place) is always a problem. Faye explains:

We’re what’s called “continuous cruisers”, which means we move our boat to a new mooring roughly every two weeks. It doesn’t mean we flit between a few favourite places: the rules state that we must “genuinely navigate the waters”, and I’ve heard of boaters’ licences being revoked because they haven’t covered enough distance.

Luckily, continuous cruising has benefits: moving every fortnight means we’re always bumping into boaters we know, which is lovely, and the sense of freedom is unparalleled.

According to her website, Faye is “working on a memoir about my life aboard a 60 foot narrowboat,” which I for one am looking forward to.

*

An Escapologist’s Diary: Part 74. Existenzminimum

I just got back from a happy few days in Paris. I met Friend Landis who was over from Chicago for a book tour, swanned around at the AsiaNow art fair, listened to live jazz (and got hit on) at Harry’s Bar, and visited the Louvre for the first time.

What I mean to talk about today however is the hostel. I stayed in a proper hostel dorm for the first time in perhaps 20 years. I loved it and I’m going to do it again in Holland and Luxembourg next month.

Seemingly, Paris hostels have privacy curtains on their bunks, which really changes everything. The bad thing about hostels as everyone either knows or can imagine is the feeling of overexposure; that strangers might be looming over you as you sleep. But the simple addition of a curtain makes a hostel every bit as good as a Japanese capsule hotel. You can still hear people moving around in the room at night, but I found it oddly comforting; you can tell from their soft movements, careful not to cause a fuss, that they’re just sleepy travellers the same as you.

For about £30 (instead of the £100+ you’d need for a hotel room in a city like Paris) you get the privacy of your bunk (in which there’s a reading lamp, a socket for charging your phone, and some little shelves for anything else you like to have nearby in the night), a locker in which you can stash your bag for the duration of your stay (actually a cube-shaped chest with a padded lid, good for sitting on to remove or put on your shoes), and access to the communal kitchens and toilet/showers.

Sorry to rattle on excitedly, but I am excited. I really enjoyed all this.

The toilet/shower rooms are much like the ones you’d find at a modern gym: by which I mean private shower cubicles, not the horror of shared showers like the ones in which footballers practice their heterosexuality. The kitchens, I was surprised to see, were spotlessly clean but well used: as well as being a casual social space for strangers to chat, I saw travellers preparing decent meals in there like fresh soup and spaghetti. (I just used it to fill my water bottle before vanishing off into Paris for pastries and cocktails).

There was also a cafe-bar in this particular hostel. I assumed it would be a basic affair for weary travellers so I dropped in on my first night with a plan to read my book over a quiet pint. But there was a jumping party going on! Glamorous drag queens were spinning records while the well-dressed Parisian youth gyrated and laughed and mingled. The place felt like the colonial bar in Lawrence of Arabia where he demands lemonade after crossing the desert; it was decorated with strings of muted lights and lazy palm fronds.

I was wearing my smelly Montreal Bagel t-shirt and some old jeans, so I was hardly presentable for it. I thirsted for that beer though, so I courageously ensconced myself at the bar and chatted with a bar worker who wasn’t bothered about my grotesque appearance and texted with my partner at home who assured me I was beautiful. I felt too self-conscious to read though, so I quaffed my refreshing blanche and made a dash for my bunk.

Sleeping with that curtain closed was a bit like being on an overnight ferry or a sleeper train without, obviously, the sensation of motion. For three nights in my coffin-like quarters, I slept like a brute.

The hostel struck me as quite the model for living. It was my socialist motto of “private sufficiency, public luxury” taken to the extreme and placed under one roof. I was happy to be far from material responsibilities and domestic maintenance. I think I could have worked on my books there if I’d wanted to.

If my partner ever throws me out, I’ll look into a long-stay hostel arrangement. The existenzminimum of a bunk, a locker, and access to those shared cooking and showering facilities was extremely liberating. And when you’re not sleeping or padding around in the communal spaces, you’re out there in your new town, living.

*

Be frugal, be free. New Escapologist Issue 14 is available in print and digital formats now.