Get in and Boogie

From Stephen King’s The Stand:

Larry felt a strong and guilty impulse to just turn tail and run. Go back … and get the Z. Fuck the two months’ rent he had just laid down on the space. Just get in and boogie. Boogie where? Anywhere. Bar Harbour, Maine. Tampa, Florida. Salt Lake City, Utah. Any place would be a good place, so long as it was comfortably over the horizon.

*

Willenbecher

I’ve been watching these short video profiles of the loft-dwelling generation of New York artists. It’s fun to see how these artists live, work, and how they all remember hanging out with Warhol.

They also all seem so young despite being in their 70s, 80s, and 90s. The reason for their youthiness seems obvious to me: they don’t have day jobs to sap their energy and their time. They do what they like to do and, importantly, they do what they’re supposed to do: they’re not railroaded by some timewasting endeavour necessary to pay rent. They don’t suffer daily separation anxiety about not doing what they ought to be doing.

Today’s artist is John Willenbecher. He puts it plainly:

If there’s one thing I’ve done in my life that I think is really great, it’s that I’ve never had a job [laughs]. I’ve never had to work for somebody. I was never a trust fund baby but I’ve always somehow managed to get along.

Live on your wits, live for your art, live for ages. If you can.

*

A Dragon Started Burning My Excel File…

Would I feel the need to scroll if the view from my desk is a giant phosphorescent mushroom?

I fear the Virtual Reality future, probably because I’m an old man. So I’ll leave it to this kid to ask: could a regular 9-5 job be worked from inside Skyrim? (Skyrim being an online role-playing action game). And thanks to Friend J for sending this in.

“There are no office buildings in Skyrim,” he says, “but there are places where everything I want from an office building: camp sites).”

*

We Launched!

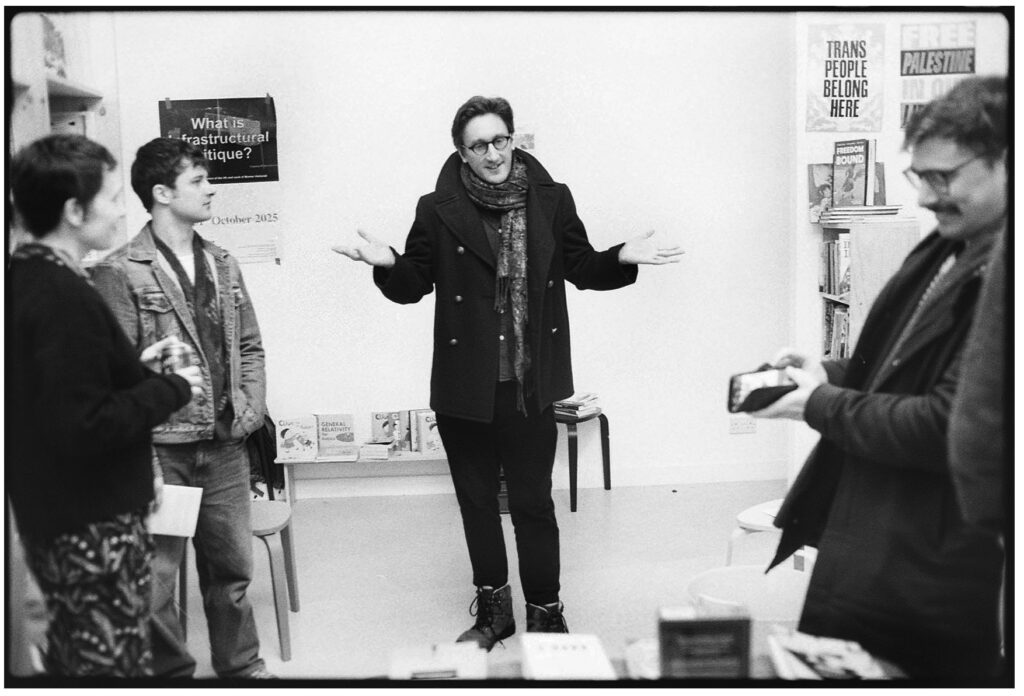

We launched! Issue 18 is now, as they say, a thing.

The issue marks the beginning of a new cycle of four. Thanks to everyone who ordered a copy or subscribed. Copies are now working their way (slowly) to Escapologists all over the UK, Continental Europe and North America.

The launch took place at Aye-Aye Books (with an after party at Ryan’s Bar) on 20.11.25

Thanks to Martin, Samara, Brian, Neil, Alan, Hilary, Jay, Leo, Callum, Jack, Fergus, Bunker, Laura, Johnston, and all the rest of the gang for making it a superfine night.

The colour shots are by Neil and the black-and-whites are by Alan.

The Burnout Society

The modern man thinks that everything ought to be done for the sake of something else, and never for its own sake.

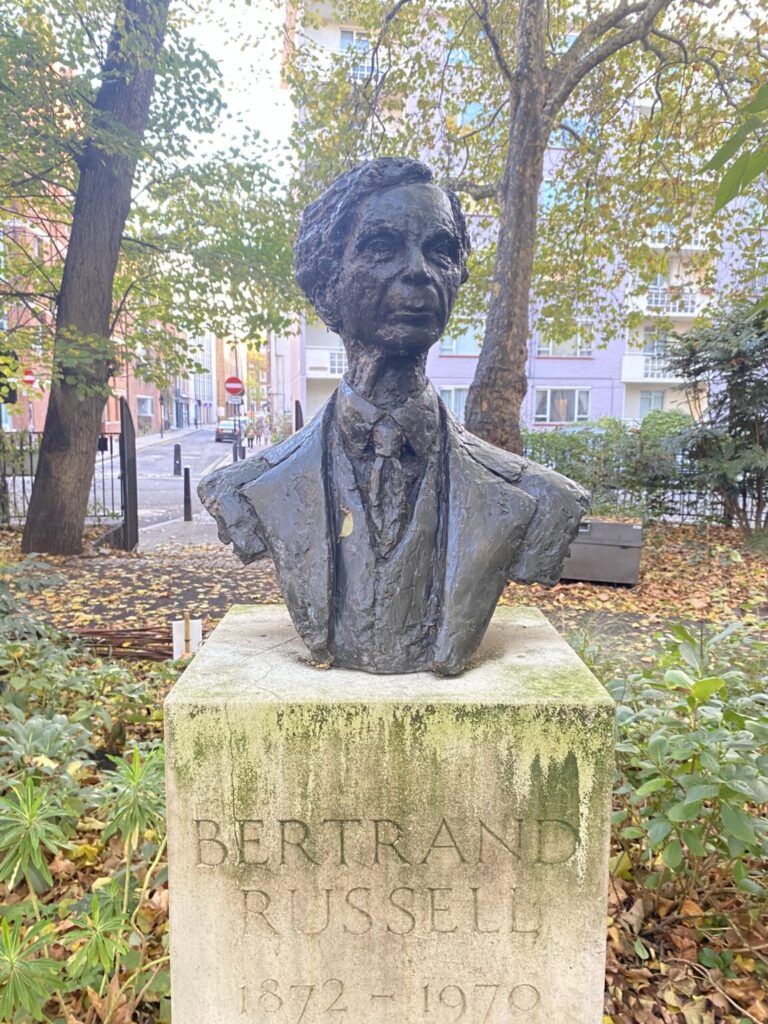

This is rather good. In the second half of the video, Henderson gets into the topic of idleness — the quote above comes from Bertrand Russell’s In Praise of Idleness — but he relates it all back to the relentlessness of 21st-centurt bullshit jobs and digital screenburn.

Burnout? See also: rustout.

Incidentally, I was hanging out with Bertrand only this week:

*

New Escapologist Issue 18 is shipping now. Go get ’em, tiger.

Running Away Works

Check this out, from comedian Marc Maron:

Running away works. Sometimes you have to change it up: new people, new restaurants, new Laundromat, new barista, new life. Yeah, the adage is true — that wherever you go, there you are — but you in an entirely new setting is a new you, or at least the old you in a new context, and that’s not nothing.

From his 2013 memoir, Attempting Normal.

*

Work is Already Broken

The Old Web — the vast network of independent websites and blogs — is thriving.

Here’s a post from someone who doesn’t like to work from home:

For a corporate employee, working from home often tops the wishlist. But I believe it creates more harm than good.

I disagree. And that’s fine.

But someone else disagrees too and writes and elegant response, not on some horrible platform but on their own longform blog:

the crux of [their] argument is [that] people who worked remotely for two or more years lost their social skills. They became shy, reserved, and confined to their comfort zones and small groups. They forgot the art of striking up conversations with strangers. They forgot how to have fun with people. … To which I say bullshit. … I know how to entertain and amuse myself.

“My whole lifestyle,” they write, “is only viable because I work remotely and have been for more than half a decade. ”

Same here.

The original blogger reckons that working in an office is a social opportunity. Maybe to some people it is, but to me it never was. Work is work: an economic arrangement. You will not meet many cool people, people you have much in common with, people you’ll want to stay in touch with, through a full-time day job.

Part of the problem is that nobody really wants to be there; we’re just economically bullied into full-time work where physical attendance is part of the cost of doing business.

Another part of the problem lies in recruitment and selection: it doesn’t exist to build a community in which people will get along and make friends, it exists to solve market problems. The best you can say really is that you’re all being ripped off equally so you have something to bond over on that front. But that’s no good because cynical conversations about being bored and having no money absolutely suck. Besides, we’re not ripped off equally: people at different levels of corporate hierarchy are being ripped off in different ways and it’s not accidental that a micro form of class struggle takes place between people on different levels of the organisation. Bah.

Thing is, work is already broken and no amount of pretension is going to return everything back to pre-covid era. Heck, pre-cloud era.

A Huge Weight Lifted Off My Shoulders

Here’s rare reminder at New Escapologist that a [part-time] day job might be the solution, not the problem. This would be if the thing you seek to escape is an untenable freelance environment or some sort of runaway self-image.

Yes, we talk here an awful lot about escaping day jobs because day jobs seem to be the #1 source of misery in the world and the one that most people secretly want to escape. But Escapology is flexible. You can escape into a jay-oh-bee if that’s what the circumstances call for.

Here’s a blogger called Megan:

At the time I saw having to get a day job as a sort of defeat. My dumbass mid-to-late twenties self thought that having a day job meant you hadn’t truly “made it” as an artist, and although I haven’t really thought that in a long time, that critical voice will still come up sometimes.

But music work had been slow for awhile. So I figured I’d just get a part-time job to have some stable income until the industry was in a better place, and I’d work my butt off in the meantime to try to get as much freelance work as I could.

Something interesting happened almost instantly, though. As soon as I started at the day job, I felt a huge weight lifted off my shoulders. Having an income was no longer dependent on me going to networking events or making social media posts! All I had to do was show up and do my work, and I’d get a paycheck every two weeks for around the same amount of money!

By getting over herself and taking the part-time day job, Megan was able to be more selective about the freelance work she accepted. She was able to start enjoying music composition again (her creative career), was less likely to accept bad gigs just for the money, and didn’t have to hustle so much.

I think the key is trying to build your life in a way that will bring you the most joy and least misery, regardless of what people say you “should” be doing. In a perfect world, I would be one of those lucky composers who makes a decent salary solely working on really cool indie projects. (Well, actually, in a perfect world there would be no money or bills, but let’s not get into that whole thing). But the world is not perfect, so I need to do what I can to build my life in a way that works for me.

Cool.

*

Hark, a Bum

I’m totally useless and a drain on society fulfilling no beneficial function whatsoever. I’ll be 50 in one year. I have nothing to show for myself; no addictions, no high blood pressure, no ulcers, no cholesterol problems; no health problems physical or mental other than the occasional guilt over failing to be a great American entrepreneur.

Thus wrote columnist Tom Chartier in “I am a Bum” in 2004. Let’s skip over the obvious smug remark that maybe Tom shouldn’t have anchored his life goals in Conservative Libertarianism. Come over to the light side, Tom. We have fun here.

But, wait, it looks like he comes to that conclusion himself:

I’m a house husband [now]. My job is to hang out with my son. Oh sure, this means I won’t get the penthouse suite, a company limo and will never get to sit with Wayne Gretzky in his luxury box at the Staples Center but I don’t really care. I will also never get to make underlings squirm in terror at the thought of being told their services will no longer be required, but “say hello to the wife and kids and don’t forget the fruit basket on your way out.” Oh sure, it’s a sacrifice but I am willing to make it. Oddly enough, unlike most of the big Kahunas out there standing center-ring running the show, these things don’t give me any satisfaction. I don’t even enjoy humiliating people, ruining lives or squashing bugs. So I guess there’s no point in me running for office but…I don’t care!

Now you’re getting it, Tom.

Chartier eventually escaped to Grand Cayman in the Caribbean where, ironically enough, he found his version of:

the American dream: No job. No taxes. No winters. No smog. No commute. No military. No Wal-Marts. No terrorists. No crime. No Piggly-Wigglys. No war mongers. No Americans. Well, er, there are a few of us here but we’re in the minority. … we’ve all fled something or another for a better life. I certainly have.

A couple of months after posting the above, Chartier claimed that his declaration of bummery has touched a nerve, that “many readers out there seem to be inspired by my total lack of success. Cries for help have poured in from across the land.”

Why, he’s just like me.

And so, in a step-by-step guide to being a bum, which is actually rather wise and very funny, he ends up advocating for minimalism, downsizing, going car-free, contemplation, choosing the right location instead of the default one, binning off the idea of career, and generally taking it easy.

He concludes:

The trick to being a bum is all mental. It’s all up to you to identify what is really important in your life and what is extraneous balderdash.

Then, and only then, you must have the courage and commitment to flush the useless turd blossoms of your life down the swirly bowl and take the plunge. Go West, Middle Aged Man! Go West and fail! Or go East if that works.

*

New Escapologist Issue 18 is shipping now. We also have a launch event in Glasgow on 19th November. Come along if you’re nearby!

Smart-Arsed Urbanites

It was supposed to be a clean break from their humdrum existence in a dingy Manchester flat. But all Max Scratchmann and his partner, Chancery, did when they moved to the Orkney Islands was replace one vision of hell with another.

This is very funny. Scratchmann escaped badly and was forced to live with the consequences.

Chucking It All: How Downshifting To A Windswept Scottish Island Did Absolutely Nothing to Improve My Life was supposed to be a light-hearted warning to “smart-arsed urbanites”, tempted by the idea of escaping the rat race, who thought that starting a slower, rustic life somewhere like Provence, Umbria or the Outer Hebrides would somehow find them inner harmony.

but:

the writer’s satirical travelogue about six years among the islanders – whom he describes as “staid, emotionally repressed drunks, stuck in the 1950s” – has so enraged inhabitants of the Scottish archipelago that it has been shelved by his publishers, after threats of legal action.

Whoops.

It’s a reminder, I suppose, to do your research before leaping blindly into an escape. Or at least to visualise it realistically. I mean, what was he expecting? If social life is important to you, a remote island might not be the place to go.

But it’s also a reminder not to be a dick about your new roomies. Not everyone has resolved to escape their own “dingy Manchester flat,” or their equivalent of it.

Still, an adventure is an adventure is an adventure. Scratchmann at least has a story to tell. Even if it had to be pulled from print.

*

New Escapologist Issue 18 is shipping now. We also have a launch event in Glasgow on 19th November. Come along if you’re nearby!