Xodus: Escaping Twitter At Last

I’m here to tell that you don’t need to be on Twitter anymore. The network effect is broken and you can finally escape its clutches. (And you should!)

If you’re a browser of Twitter, you probably see a lot of crap. It’s no longer your friends or even organisations you’re actually following anymore.

If you’re a creator who once used social networks to grow your audience, those followers aren’t seeing your tweets anymore. Here’s Cory Doctorow on the facts:

Six months ago, [Radio station and publisher] NPR lost all patience with Musk’s shenanigans, and quit the service. Half a year later, they’ve revealed how low the switching cost for a major news outlet that leaves Twitter really are: NPR’s traffic, post-Twitter, has declined by less than a single percentage point.

NPR’s Twitter accounts had 8.7 million followers, but even six months ago, Musk’s enshittification speedrun had drawn down NPR’s ability to reach those users to a negligible level. The 8.7 million number was an illusion […] On Twitter, the true number of followers you have is effectively zero […] because every post in their feeds that they want to see is a post that no one can be charged to show them.

Whenever I visit Twitter these days, I’m usually greeted by a single notification. The days of 20 or 40 ringing bells are long behind me. Worse, the notification is never a message or an RT or anything remotely useful. It’s inevitably a follow from a sex bot, i.e. some sort of phishing scam.

This daily non-experience, combined with how nobody sees my tweets anymore (either because they’ve sensibly left the platform or because I’m hidden by the algorithm) makes me realise… I’m free. Finally free! I can leave!

And so can you. Here are the instructions on how you too can leave Twitter.

It’s a shame really. Twitter was useful for contacting people and finding things out in realtime, but it just doesn’t work that way anymore. It’s a busted flush. I’ll probably lose touch with some people whose main point of contact is Twitter; I’ve contacted the ones I can think of to give them my email address.

The nightmare is over. No more Twitter.

In my case, it leaves me social media free for the first time in over 20 years! It was 2003 when I joined a platform called Friendster. I might eventually come over to Bluesky for fun, but for now I think I’ll enjoy the fresh air and resounding lack of network effect in my life. I advise you all to do the same. Deactivate your accounts and be free.

To celebrate what I’m calling the Xodus, I recommend reading this potted history of social media in The Atlantic magazine. It charts the incremental changes that took Twitter and Facebook from a useful database of social connections to nightmare of conspiracy theories and nonsense content that is ruining the world.

Now all I have to deal with is the problem of Substack…

*

Weeping in the Parking Lot

It was still dark. I left home in blackness and I returned in blackness.

Maybe a tad bleak for New Escapologist but it’s on theme.

Life on a Tiny Houseboat

Thanks to Reader S for drawing our attention to this pleasant video.

Reader S writes:

I’d experiment with this at least, if I had an extra pair of hands to help me. Plus accessibility to a canal network such as this, of course. Don’t know a thing about boats, though.

Indeed! Those are the obstacles. As we know, there are advantages and challenges of boat life.

It’s nice to see the phrase “continuous cruiser” come up again. And I also like how this man seems to have all the accents, perhaps as a result of moving around so much.

*

Our latest issue is Issue 15, available now in print and digital formats.

Letters to the Editor: Why No Photographs?

To send a letter to the editor, simply write in. You’ll get a reply and we’ll anonymise any blogged version.

Reader X writes:

Hey Robert,

Finished slowly reading Issue 15 because I wanted to suck the marrow out of the bones of Experiments in Living. Delightful!

But… why no photographs? I was so hoping to see what Henry’s humble home looked like, although admittedly you did a most excellent job in describing it. Is adding photos just prohibitively expensive or just not the aesthetic you want to pursue?

Just starting a reread. Always entertaining to hear your voice on the page. Don’t want to unduly add to your anxiety but already looking forward to the next issue…

*

Hello X,

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed it. I had a reflective read of both issues last night and I must admit to being very pleased with it all. I’m also happy that people are buying it: it feels like a magazine written just for me, so it’s validating that others are interested (even enthusiastic!) too. I feel a strong sense of connection with you and the other readers. It’s wonderful. I’m very grateful for it.

It’s funny you should mention photographs as I’ve been thinking of using photography in the magazine for the first time. Up to now, I’ve never used it in New Escapologist. As you rightly suspect, it’s not the aesthetic I want. However! This aesthetic (non-digital, perhaps a little bit Victorian) was informed by pragmatism some 16 years ago: photographs didn’t reproduce particularly well with the printing technology I used. We’ve moved on since then and we could theoretically print photographs if we wanted to.

Not photographing Henry’s place was a deliberate decision though. It would have compromised his privacy. I’m slightly amazed that he allows me to publish details about his life at all. I didn’t want to use technology (my iPhone camera) in his presence, nor would I want those pictures to find their way onto the Internet, on which he has robustly turned his back. So even if photography was technically and aesthetically possible, I would never have published photographs of Henry’s house.

Two possibilities exist for breaking my no photography rule: one is my friend Alan who takes remarkable documentary photographs (usually on film) and with whom I already collaborate a little. Another is a photo album I inherited from my friend Kat: it depicts the louche alternative life of a theatrical couple in the 1950s. I want to research the photos a little and maybe write about them. If I do this for New Escapologist (as an example of successful outsider life), it would be a shame not to reproduce some of the photos. So maybe you’ll get photographs soon! I’m mulling it all over.

Oh! You might also have noticed that the inside covers of the print edition can use colour ink now. This is available to us at no additional cost so I like the idea of using that. In Issue 15 (exclusive to the print version), the inside back cover shows the attractive modernist artwork from the cover of Escape, Escapism and Escapology, one of the books we reviewed. I decided not to label as such (though credit to the artist and the owner of the painting can be found in the masthead) to allow it to pique people’s curiosity.

Rob

*

If other readers have thoughts concerning our aesthetic and the use of photographs, please comment on this post or send me an email. Print editions of Issue 14 and 15 remain available to purchase.

A Burning Desire for the Open Air

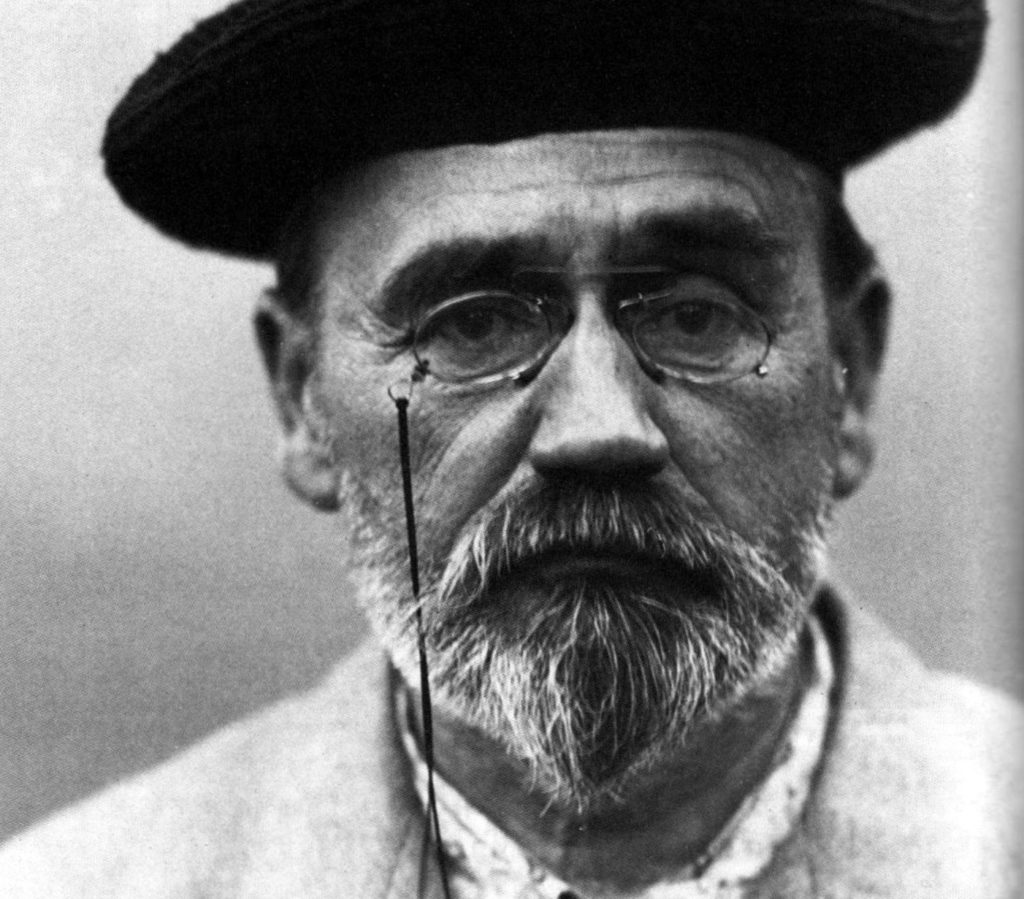

Émile Zola didn’t take any prisoners when describing the lower middle classes in 1868. I’m reading his novel Thérèse Raquin:

Thérèse, who finds herself living in stultifying domestic mediocrity, longs for freedom:

They brought me up, they received me, and shielded me from misery. But I should have preferred abandonment to their hospitality. I had a burning desire for the open air. When quite young, my dream was to rove barefooted along the dusty roads, holding out my hand for charity, living like a gipsy.

and

You will hardly credit how bad they have made me. They have turned me into a liar and a hypocrite. They have stifled me with their middle-class gentleness, and I can hardly understand how it is that there is still blood in my veins. I have lowered my eyes, and given myself a mournful, idiotic face like theirs. I have led their deathlike life. When you saw me I looked like a blockhead, did I not? I was grave, overwhelmed, brutalised. I no longer had any hope. I thought of flinging myself into the Seine.

This reminds me of a film I saw recently called His House. It’s a horror film about Sudanese refugees who must start a new life in the English Midlands. Of the low-level English pen-pushing bullies they encounter, they say:

They don’t want to be reminded that it is them that are weak. How poor and lazy and bored they are.

It’s not only homelife Zola despises. He really takes aim at the office. People who want to work in offices, represented by Thérèse’s meek husband Camille, are idiots and try-hards. Her secret lover Laurent meanwhile, a more creative fellow albeit not a successful one, must also work in an office but against his will:

With stomach full, and face refreshed, he recovered his thick-headed tranquillity. He reached his office and passed the whole day yawning and awaiting the time to leave. He was a mere clerk like the others, stupid and weary, without an idea in his head, save that of sending in his resignation and taking a studio. He dreamed vaguely of a new existence of idleness, and this sufficed to occupy him until evening.

In Zola’s world, some people (like Camille) are idiotically seduced into The Trap by empty promises of status. Others are pushed into it by circumstance: through financial desperation or through their failure to do something better. Loverboy Laurent isn’t a very good portrait painter but, when left to his own devices later in the book, he starts to thrive. Time and space are what he needs but the system denies them to him.

Laurent’s failure to live up to his real calling and Thérèse’s deep domestic boredom lead them on a chaotic path of adultery and murder. They become a social problem. The system fails individuals, obviously, but in doing so, fails us all.

*

An Escapologist’s Diary: Part 76. 2023 Review.

Baboosh! Time for an annual report to my imaginary shareholders.

But first an excerpt from last year’s report:

I had the privilege of working hard and attentively this year […] though I have nothing tactile to show for it yet. Soon, my pretties, soon. Next year’s review will be massive.

Indeed. I don’t mean to brag (though to brag is better than to humblebrag) but 2023 was probably my best ever year. I was happier and more focussed than any year since 2016 and possibly any year before that one. It was full and fun.

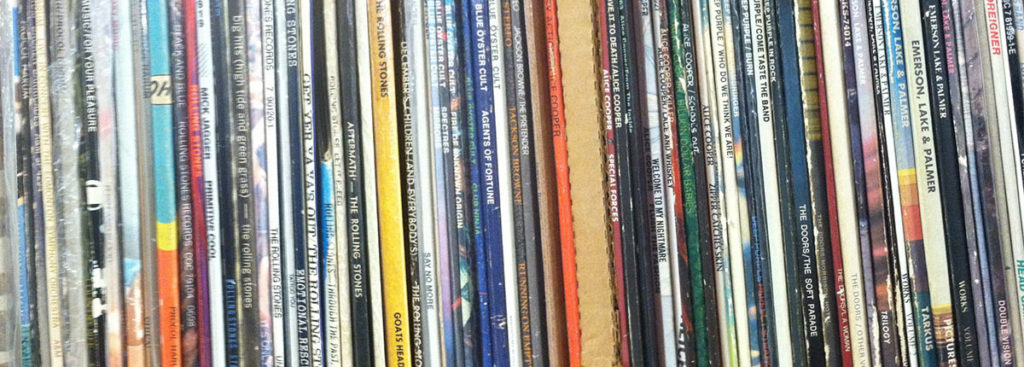

Minimalism vs The Cloud

My stereo system (a turntable, two bookshelf speakers, an amplifier, and about 30 vinyl records) is a disgrace to my minimalism. I don’t need it and I don’t love it. But I do like it. As one school of minimalism would put it, it sparks joy.

I treat it as temporary. I might sell it one day, when it ceases to deliver the goods or when I need the money.

I keep wondering if I’d rather have the ullage (the empty space) instead of the stereo system. For now the answer remains: no, I’d prefer to have the records.

Part of the reason for this return to physical media was to buck against digital streaming and jab-screen devices. In many ways, I’m a 20th Century boy.

The bottom line, really, is that I don’t enjoy streamed music. Playing it has little appeal to me as an activity, so while the storage solution of The Cloud might look like a good one, it’s a failure in that the new system doesn’t actually deliver the benefits of the old one. Quitting something you enjoy without a higher goal (e.g. the plan is to move country) is no solution to anything.

I was going to write more fully about this today but, by happy coincidence, my friend Carrie just did the same. She speaks of the benefits of physical media:

It feels like [vinyl] somehow matters more, and because I’m listening with my whole self it’s much more emotionally affecting too.

[Streaming has] broken many artists’ ability to make a living from music. When you can stream pretty much everything ever recorded for less than you’d pay for a single vinyl LP, your streams are almost worthless in terms of what any artist gets paid.

and of the reservations about it:

vinyl is hilariously expensive and may need you to buy a whole bunch of new hardware too

The reasons not to buy a bunch of vinyl records remain the same as when I first put thought into this. It’s stuff. But as much as I dislike the cost and the responsibility of ownership, I also dislike the impoverished world offered by streaming.

The Cloud is a good place to stash your ugly, boring administrative documents. And it makes photographs more sharable and stops them from collecting dust. But music? Not everything needs to be invisibled away. I have real art on my walls too, not those horrible screens you can get now. And real books, not e-books. The physical world is better for you sometimes; to move around and manually make something happen is appealing to the primate brain. And we are primates.

I’m not saying every primal urge should be humoured or that everything should be analogue instead of digital but, overall, a balance can be struck in the interests of mental health and general quality of life.

I’d rather be with my partner “IRL” than look at her face on Zoom. I’d rather write notes with a pencil on paper than in an app. And I’d rather, for now, softly drop the needle into a shiny black groove instead of jab dumbly at yet another screen while wondering if I’m really hearing the proper version or if the streaming provider is punishing the artist I’m currently trying to admire, while simultaneously cursing the range of bluetooth. I mean, yawn.

I may of course feel differently about this some day. Perhaps when I next move to a different apartment.

*

New Escapologist is a friend of minimalism. Get the all-new Issue 15 in either print or digital format today (or whenever you’re ready).

Bullshit Jobs Cheat Sheet

I like this website. It’s an angry single-page summary of the Bullshit Jobs economic scenario in which our global society is ensnared. Or, as its author puts it, “a crude attempt of helping people to understand humanity’s #1 issue.”

And the Number One issue it surely is. Yet so few people describe it as such or talk about it so directly. Our economy should work to push money around to the places it’s needed, but instead we’re hollowing out the Earth and enslaving billions of people (often literally) to generate vast batteries of pointless wealth for tiny coterie of bastards.

We are 30+ years past said peak labor efficiency but continue to maintain the obsolete work-for-income paradigm. With fatal implications and consequences.

Instead of finally decoupling income from labor and distributing the wealth generated by our actual economy, we maintained this narrative of “never-enough-jobs”. [This has led to] to billions of purely systemic and/or redundant, non-contributing bullshit jobs.

The site quotes Thomas Jefferson, our forever boyfriend David Graeber, Margrit Kennedy, and Alan Watts. (I’ve never read Alan Watts. I think I prefer E. F. Schumacher when it comes to hippie economics but Watts’ name comes up a lot and he’s a goodie for all I know. The cheat sheet describes him as an early advocate of socially-responsible automation and UBI).

Most powerfully of all, the site reminds us that all of this pointless toil, as well as ruining lives and promoting staggering injustice, is destroying the planet. “To save the world,” it quotes Graeber as saying, “we’re going to have to stop working.” Graeber was right.

*

I Preserved My Freedom

In old books and films, I sometimes spot an indication that it was easier to live frugally in the past than it is today.

Ah, but wages rise with inflation you say? Well, that’s sometimes true. But there’s also the Big Mac Index to think about.

Anyway, I spotted another example today. It was in a memoir, written in the ’70s and recounting events from the ’60s. The passage refers to life in 1966:

At this time I was doing the book-keeping for Michael Rainey’s shop for £10 a week. I only had to go in a few times a week and balance the accounts, so it suited me well. I preserved my freedom at the same time as getting an income. Michael had been in the position of having no money himself and he appreciated the difficulties.

Now. There are a few things to say about this. First, there’s this business of living on a tenner a week. I am exceptionally frugal and have been connived a low-income/low-expenditure situation to arrive at weekly expenses of £130 (I spend more in reality but that’s the amount I need to stay housed and alive). A more typical figure is £628 per household per week (so £261 per person based on the UK average household size of 2.4 people). While £10 in 1966 might be a sum of money trivial enough to be called “a tenner” and to give away to a silly friend, I don’t think many of us would part with £261 a week on a similar wheeze today.

Second, I suppose the requirement to “go in a few times a week” would still hamper your freedom to an extent. You can’t just leave the country on a whim. You have to put clothes and shoes on. The phone could ring while you’re relaxing in the bath. But it’s a hell of a lot better than a full-time job. I’d do it. Also, 1966 was a more tactile, physical world: going out to accomplish things, riding buses, and physically tickling through paperwork were more normal and it wouldn’t be such an affront to freedom as it would be today with our networked digital technology. I think I’d like that physical world better in a way: all those cigarettes and pencil sharpeners and vacuum tubes would be fun. I could be wrong.

Third, working people, as a general rule, can’t afford the sort of empathy exhibited by the memoirist’s friend. We have our own troubles, our own desperate shortage of money and time and patience. Urgh. What a wretched age. Send me back in time NOW!

*opens one eye.* Did it work? No? Blast. Well, at least the Internet keeps me out of trouble. Mostly.

*