Canadian Hermit

And here’s one last thing about hermits, if you can take it. A silly piece I wrote in my personal blog this spring:

“Sorry brain, back in the freezer.”

This is what I say when it’s time to go out in the Montreal winter. At -30°C, you become aware that your physical brain might not be having a terrific time.

That’s not really acceptable in the civilized world, is it? You should never be put in a situation where you’re moved to apologise to your brain.

When my brain didn’t complain about the cold today, I felt genuine concern. Had it died? Had Quebec murdered my brain?

No. Something was different. The snow was melting. Green buds had appeared on the trees. All around, I could hear the rumbling tummies of a million defrosted tardigrades.

Were we above zero? Spring! Spring was here!

“Spring is here, old woman!” I said to an old woman.

“Va chier,” she said (or in English: “Rejoice, rose-cheeked young sirrah!”)

“Spring is here, bedraggled pigeon!”

“Coo,” said the pigeon, perched on a plastic owl.

“Spring is here, plastic owl!”

The plastic owl looked pissed off.

A small man with a bushy beard and a red cycle helmet was standing and stinking on the street corner with a can of something called Pabst Blue Ribbon.

On seeing him, I stopped dead in my tracks. Scrotters? It was Scrotters! His presence was as surprising and wonderful as the spring itself.

My instinct was to plant a big wet kiss on his mouth and say “Spring is here, Scrotters, old friend, and–what’s more–I love you!” but kissing a tramp is inadvisable even if you’re a tramp yourself.

Besides, “Scrotters” is probably not his real name, merely the one I’ve rather offensively given him in the privacy of my head.

If only there were some way to learn his real name. But there’s not.

I’d been worried about Scrotters and it was a relief to see him after such a long time. He’d disappeared from his corner four months earlier, mysteriously replaced by a far-stinkier and more aggressive tramp. The new tramp’s secret name was Lion Man because he looked like a lion and ate raw meat.

Lion Man, I imagined, had frightened Scrotters away and stolen his lucrative corner.

I didn’t think the battle for the corner had been too bloody, just that Scrotters had been forced to move along by a trampier tramp. After all, Scrotters had that helmet. He was indestructible.

All the same, I didn’t like Lion Man. When I didn’t give him money, I got the impression he was silently hating me. Scrotters, under the same circumstances, would always growl and call me a shit owl, but there was never any malice in it.

Before his disappearance, Scrotters rarely if ever left his corner, which provided our neighbourhood with a welcome sense of certainty. Lion Man, on the other hand, spent half of his time on the opposite side of the street, spreadeagle on the ground, catching snowflakes.

You never knew what to expect with Lion Man. It was chaos.

Before the tramp replacement, we’d always been able to see Scrotters from our kitchen window. Every morning, his helmet would catch the bleary eye across the granola.

Each day, one of us would remark to the other something along the lines of “Oh look, someone’s bought Scrotters a massive pizza,” or “Oh look, Scrotters is wearing his cross-country skis.”

When I arrived back home today, I was very excited to report to my girlfriend that our favourite tramp was safely back on his corner of choice.

“Scrotters is back!” I said.

“Scrotters?” she said, “Where do you suppose he’s been?”

For a brief moment I wondered if his triumphant return was actually a tragedy. What if Lion Man had been nothing to do with his absence and Scrotters had actually been living in a luxuriously-carpeted house for four months but he’d lost it all again and wound up back on the corner.

“He must be the summer tramp,” I said, dismissing the rags-to-riches-and-back-to-rags-again story I’d witnessed in my head like Captain Picard in The Inner Light, “Lion Man must be the winter tramp.”

“Of course,” she said sarcastically, “Lion Man can withstand the winter because of his glorious mane. Scrotters probably goes down to Florida. He’s a snowbird.”

“See for yourself,” I said pointing out of the window, “One Scrotters.”

There he was. Standing on the corner, as was his way, like a stranded astronaut. A harbinger of spring. Skinny with his red cycle helmet, from this distance he looked like a safety match.

“Are you sure it’s him? Lion Man didn’t nick his helmet?”

“Nah, it’s Scrotters,” I said. “He’s unmistakable.”

“Aw. Prince of Tramps,” she said, finally getting into the spirit of things.

“The Original and Best,” I said.

“Captain Corner,” she said.

“The Pedigree Chum,” I said.

“Can we stop talking about Scrotters now?” she said.

“Okay, I said.”

I was glad he came back though. From now on, I’m going to give him a coin every single time I pass him. I’m also going to pretend I’m a wealthy country gent and that Scrotters is my personal hermit. “Look,” I’ll say to visitors, “look at my hermit.”

And there he’ll be.

★ Help fund the forthcoming Escapology book. Order a copy today

A Hermit in New York

Here’s Canadian humorist Eric Nicol, one of my heroes, writing in 1950:

Here […] is a newspaper story about a man named Paul Makushak, who has been dug out of a dank cubbyhole in a Brooklyn tenement after 10 years of isolation, during which his mother fed him through an opening in the bedroom ceiling. The mother sealed him up in 1939 to cheat the draft. One paragraph of the story reads: ” ‘I like it in there,’ he (Makushak) said. ‘I’d like to go back. I don’t care about the outside world.’ Police took him to a hospital.”

Now, why do you suppose the police would want to go and do a thing like that? According to this account, Paul wasn’t ill or anything. He was barefoot, filthy, and partially obscured by 10 years’ worth of beard. But some of the happiest and healthiest people I know fit that description, and nobody tries to hustle them into a hospital. Not yet, anyhow.

Come to that, what right had the police to drag poor old Paul out of his cubicle in the first place? He said himself that he liked it there. Is it now considered an offense to cut yourself off to the outside world? Are hermits outlaws?

We in Canada, so rich in hermits, can hardly afford to ignore the implications of the Brooklyn case. If the hermit, in the very nature of his isolation, has lost the right to vanish into his own beard, let’s say so. Let’s at least give the hermits a chance to form a union, to strike for freedom of silence, freedom of disassembly, freedom of solitary confinement. If a man can’t sit alone in a gloomy 3×5-foot cell without fear of police crashing through his wall, who of us can again feel safe in certain prairie hostels?

Maybe the police argued that Paul was potty. Maybe they took him to a mental hospital on the grounds that nobody in his right mind would abstain from organized society. Well, a seventeenth-century philosopher named Pascal, who was certainly in somebody’s right mind, once wrote that all of man’s troubles arise from his inability to remain alone, tranquil, in a room. Pascal was a Jansenist, a set that shut itself off from the world and let God nourish it through a opening in the ceiling they called Heaven.

Too, both before and since Bunyan, who tossed off Pilgrim’s Progress while in the hoosegow, men have done their best thinking in a box, the candle of the mind burning most steadily when undisturbed by gusts from the senses.

So perhaps Paul Makushak was winding up 10 years of intensive and entirely satisfactory thinking, when they found him. Perhaps he was on the verge of solving the riddle of existence when the crowbars smashed into his wall and he blinked up into the great, unrewarding face of a Brooklyn cop. And perhaps he is now walking the streets of New York, cleaned, shaved and booted, wondering at his promotion to that larger and noisier cell, that superior isolation in which even the police are no longer interested in him.

Just conjecture, I admit. The chances of Paul’s being a Pascal are skinny. But, the important thing is that if we had a Pascal he might easily resemble Paul–rags, cubbyhole, thick matted hair and all. I can remember when Ghandi was just a prop for gags about sheets, and a lot of people think about Einstein as the man who needs a haircut. Might we not therefore suggest that the police be less quick about lashing out with crowbars? They could enquire, don’t you think that the Mr. Makushaks would prefer not to be dug up, photographed by the press, laughed over by the public, and lugged off to hospital.

After all, if we show such brutal determination to have a fellow creature share the “outside world” may we not be suspected of finding that world too little delectable for hoarding to ourselves? I seem to recall the taunt “misery loves company” but that can’t be à propos can it?

*

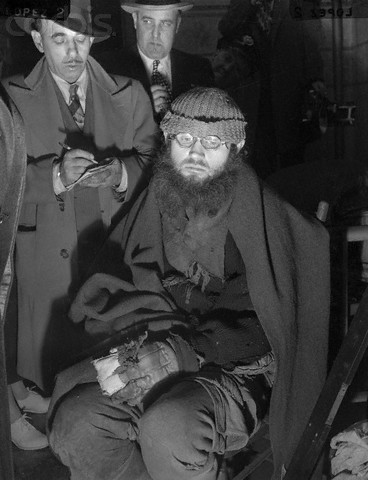

Paul Makushak was a real person, by the way, and here’s what he looked like:

★ Help fund the forthcoming Escapology book. Order a copy today

American Hermit

For nearly thirty years, a phantom haunted the woods of Central Maine. Unseen and unknown, he lived in secret, creeping into homes in the dead of night and surviving on what he could steal. To the spooked locals, he became a legend—or maybe a myth. They wondered how he could possibly be real. Until one day last year, the hermit came out of the forest.

I’ve always been intrigued and delighted by hermits. Thanks then to Robert Day for showing me this via our Facebook page.

This fellow survived in the woods through stealth and petty theft. A shame maybe, but the bigger crime is surely not providing any decent, more sanctioned way out of society.

★ Help fund the forthcoming Escapology book. Order a copy today

The Ice Cream Van

A random and rather dark memory of office life.

An ice cream van would sometimes pull up outside the building, playing its cheerful ice-cream-van melody from the car park.

Sometimes, a few office workers would actually go outside to buy ice cream cones, returning to eat them at their desks. The first time I saw this, I found it rather charming: suited-and-booted middle-managers sitting on swivel chairs, licking their Mr Whippies.

Anyway, the only tune the ice cream van ever seemed to play was “The Liberty Bell” by John Philip Sousa, better known as the theme tune to Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

When that music started up, we’d all laugh nervously. We weren’t laughing because it made us think of Monty Python or even because it reminded us of those better, sunnier, Ray Bradbury days spent playing outdoors as children.

We laughed because the trundling, tumbling first few notes of that tune provide a strangely delirious, imbecilic, we’re-all-going-to-Hell-but-that’s-okay, carnivalesque “descent”. Listen to it and maybe you’ll see what I mean.

It reminded us all that, sitting there in front of our computer screens day-in day-out, we were slowly–and with some complicity–losing our marbles.

★ Help fund the forthcoming Escapology book. Order a copy today

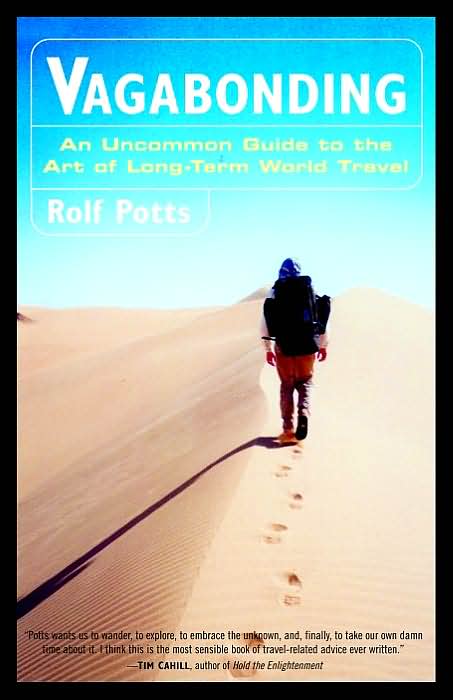

Vagabonding

These are the underlined passages–perhaps the ones best relating to Escapology–in my copy of Vagabonding by Rolf Potts:

You don’t have to be rich to escape in the first instance:

the idea of a stack of money and a tropical getaway […] is an escapist cliche and you don’t need to rob a bank to prove it. Just take a modest, nonheisted sum–five grand say–to a quiet inexpensive beach in Guatamala, Greece, Goa and see what happens.

Indeed, the freedom to go Vagabonding has never been determined by income level: its found through simplicity — the conscious decision of how to use what income you have.

There’s nothing wrong with escaping and then coming back. You can always reintegrate if necessary:

don’t worry that your extended travels might leave you with a “gap” on your résumé. Rather, you should enthusiastically and apologetically include your vagabonding experience on your résumé when you return. List the job skills travel has taught you: independence, flexibility, negotiation, planning, boldness, self-sufficiency, improvisation.

A caution about your Escapological motivations:

It’s important […] that you never go vagabonding out of a vague sense of fashion or obligation. Vagabonding is not a social movement or a moral high ground […] It’s a personal act that demands only the realignment of the self.

And a single word:

adventure

★ Help fund the forthcoming Escapology book. Order a copy today.

3 Reasons to Never Take Another Job

This is from a very good essay by entrepreneur Corbett Barr in which he explains succinctly why self-employment beats the hell out of working for someone else.

These aren’t feudal times. If you live in the free world, there is no reason you have to work for someone else. The freedom to pursue happiness and live the life you desire is the greatest gift of modern society, yet most of us piss that opportunity away.

When you work a job, someone else is ultimately in control of what you work on, what you’re responsible for, when you work, when you take time off and how much you earn.

If you absolutely love your job, perhaps giving up that amount of control is worth it. For most people, it seems insane to accept those conditions.

Help fund the forthcoming Escapology book. Pre-order a copy today.

Sorry — The Sun is Shining so I’ve Gone to Sleep on a Hill

You can escape — if only for one night — and find nature, wilderness, a bit of peace and then go back to your normal life with a slightly shifted perspective.

This is travel writer Alastair Humphries on his idea of the “microadventure”.

The idea is that life-enhancing travel need not require huge tracts of time or planning; that you can in fact sleep beneath the stars on weekends and be ready for work again on Monday.

Naturally, at New Escapologist we prefer a more full-time adventure, but taking the opportunity to enrich your life in this small and manageable way is fairly irresistible no matter what your daily experience looks like.

Besides, you can always enjoy a microadventure without being a slave to the weekend. Look at Alastair’s out-of-office message:

Sorry — the sun is shining so I’ve gone to sleep on a hill.

Help fund the forthcoming Escapology book. Pre-order a copy today.

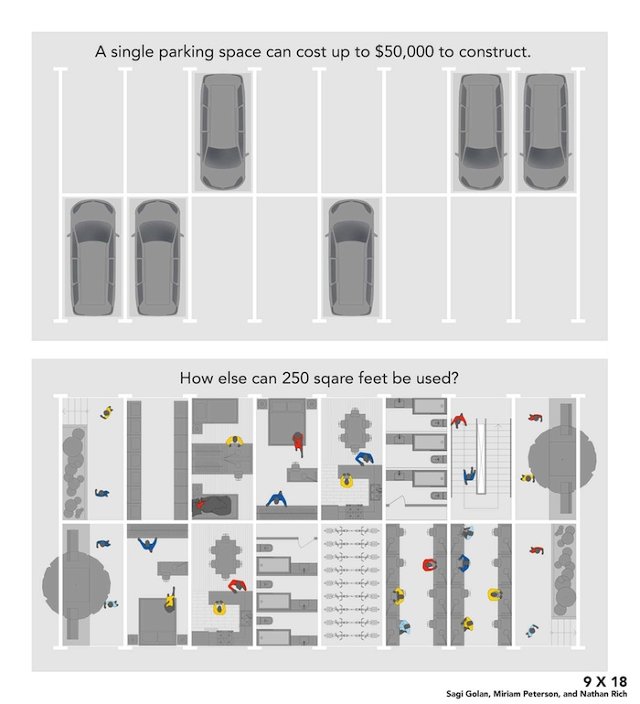

Park It In, Man

Imagine how beautiful our cities would be with no cars in them. The clean air. The safe streets. The polite sounds of conversation and twittering birds instead of the roar of traffic.

Imagine the convenience and cost efficiency of teeny little downtown houses instead of big ones further out of town. No commutes. No massive mortgages or heating bills. Proximity to all the cool bars, cinemas, universities, libraries and shops.

Possible solution? Replace parking spaces with neat minimalist homes.

Just try not to think about the idea of metered housing.

Help fund the forthcoming Escapology book and pre-order a copy today.

On Marketing

I’ve been doing my best to promote the New Escapologist book.

Marketing always makes me feel uncomfortable, partly for ethical reasons but mainly because I’d rather be doing something else, like reading P.G. Woodhouse books in my gently-rocking my hammock. That’s what summer is for.

Whatever the reason, even just politely inviting people to buy my stuff or asking them to tell others about it really takes something out of me. I largely enjoy tabling at book fairs, for instance, proudly representing New Escapologist and signing copies for friendly people. But even this level of promotion inevitably leaves me exhausted and spending the whole of the following week in a vegetative, convalescent state.

This puts me in mind of an article I wrote last year for a marketing blog. I met the nice lady who runs the blog at (of all places) the Montreal Anarchist Bookfair. I think she was looking for someone who wasn’t a natural marketeer but somehow muddled through.

I said I’d do it. No cash offered, of course, but I thought I’d win some of their readers over and make a few naughty jokes about marketing people (most of which, to their credit, made the edit).

In the piece, I express my aversion to marketing, explain how we sell New Escapologist, and also re-tell the magazine’s origin story. Here it is:

We’re Escapologists

Escape is thrilling: the wind rushing through your hair as you scarper as quickly as possible, resisting the temptation to look back to see if they’ve found your note yet.

It can be an unbeatable high. But it can also be the most reasonable, economical and practical course of action.

Not that you’d necessarily know it. We’re not generally encouraged to see commitments to things like work or shopping as the traps they are and as such escapable. British culture instead promotes endurance, to grin and bear it no matter how bored or miserable you are. American culture encourages fight over flight, to go down with all guns blazing.

There aren’t enough people saying “Sod this. I’m getting out of here. Pass me the good tunnelling spoon.”

Those who give up and walk out are too often considered cowardly, uncommitted or, oh dear, “a quitter”. The pupil escaping double maths by playing truant is punished. Those who escape the workforce are considered lazy or wasted or eccentric. Emigrants are viewed with suspicion, though their only crime was to stray from the landmass they happened to be born on.

This is all rather silly. We should respect people who take action by quitting the jobs they hate, leaving the partners they no longer love, fleeing the cities they find depressing, and abandoning traditions in which they find no value.

The will to flee was once considered a mental illness. Drapetomania was the apparent madness responsible for a plantation slave wanting to escape his captors. An American physician called Samuel A. Cartwright named the condition and explained that it could be seen where a slave became “sulky and dissatisfied without cause” and could be prevented by “whipping the devil out of them”.

In his eyes, being forced into backbreaking unpaid servitude was not considered adequate cause for “dissatisfaction”.

The Nazis were anti-escape too. Those who attempted (or were thought to be plotting) escape from concentration camps were branded with a Fluchtverdächtiger badge in addition to the badge representing whatever crime against Fascism had originally brought them to the camp. Not only was it awful to be born Jewish or gay or simply workshy, it was equally contemptible to want to escape being worked to death or gassed.

Today, a CV overflowing with short-term or dissimilar jobs is seen as unprofessional or belonging to an unfocused, undisciplined individual rather than, as the case may be, someone who is sporting or widely-experienced. Frankly, a CV professing no deviation from a single career plan can only belong to a liar or a twat but employers don’t often seem to notice this.

Slave owners, Nazis and HR Managers. Those are the kinds of people who oppose escape.

Against the grain, some of us are happy to walk out on a displeasing situation. We’re Escapologists.