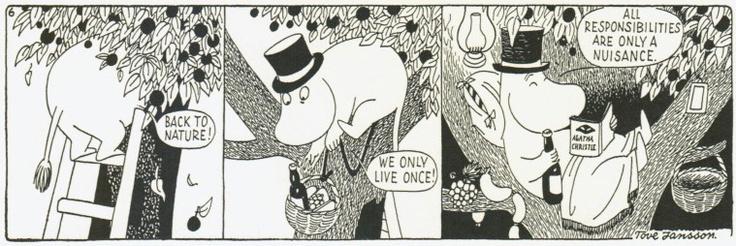

Saying It All in Three Panels

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

The They

Existentialists think that what makes humans different from all other beings is the fact that we can choose what to do. In fact, we must choose: the only thing we are not free to do is not to be free. Other entities have some predefined nature: a rock, a penknife or even a beetle just is what it is. But as a human, there is no blueprint for producing me. I may be influenced by biology, culture and personal background, but at each moment I am making myself up as I go along, depending on what I choose to do next. As Sartre put it: “There is no traced-out path to lead man to his salvation; he must constantly invent his own path. But, to invent it, he is free, responsible, without excuse, and every hope lies within him.” It is terrifying, but exhilarating.

From Think big, be free, have sex: ten reasons to be an existentialist.

However tough it is, existentialists generally strive to be “authentic”. They take this to mean being less self-deceiving, more decisive, more committed, and more willing to take on responsibility for the world.

Most of the time, we don’t do this very well. Why? For Heidegger, the fault lies with our bewitchment by a non-entity called das Man, often translated as “the they” – as in “they say it will all be over by Christmas” (or the “one” in the phrase “one doesn’t do that”). We can’t say who exactly this “they” is, but it is everywhere, and it steals the decisions I should be making by myself.

For Sartre, the problem is mauvaise foi, or bad faith. To avoid facing up to how free I am, I pretend not to be free at all.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

Bibliographed

I slightly regret not putting a bibliography in the back of Escape Everything! especially now that people have started asking why there isn’t one.

So by jove, I went back to the book and built a bibliography. Good job I have near-total recall when it comes to this sort of thing. It’s here. Happy to discuss the books and articles in the comments thread there.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

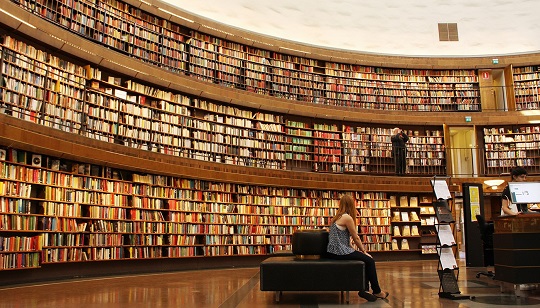

Escape Everything! The Missing Bibliography

A few people said Escape Everything! should have contained a bibliography. I’m sorry it didn’t. This was a bit of an oversight on my part. Since I’d usually name the book or article I was talking about in the main text, I didn’t immediately see a need for a bibliography. But this overlooked the usefulness of having them all in one place and missed the opportunity to talk about books, which is quite unlike me. So here it is: the missing bibliography. It’s thorough but not comprehensive, itemising the widest shoulders I stood on and pointing to further reading. Still, I hope it’s useful and fun. Most of the links go to Worldcat which can help you to find a local library copy. You can buy most of them in the usual places and I recommend Blackwell’s in particular. I’m also happy to discuss these books or provide extra information in the comments thread.

Introduction

The Houdini biography alluded to is The Secret Life of Houdini (2006) by Larry Sloman and William Kalush. Details on Lulu the vanishing pachyderm come from Hiding The Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible (2003) by Jim Steinmeyer. The quote from Adam Phillips comes from his book Houdini’s Box: On the Arts of Escape (2002). For some printed Simon Munnery, I recommend his little volume of aphorisms How to Live (2005) and my own history book about his early work You Are Nothing (2012). Grayson Perry wrote a good book called The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman (2011) and another called Playing to the Gallery (2014). Myles na Gopaleen is the Irish Times pseudonym of Brian O’Nolan (AKA Flann O’Brien), his finest peluche collected in The Best of Myles: A Selection from Cruiskeen Lawn (1968).

Chapter One: Work

Bob Black’s wisdom comes from his essay The Abolition of Work (1985) and is essential reading. The Buckminster Fuller quote comes from an article in New York magazine (1970). David Graeber’s popular essay On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs comes from Strike! Magazine (2013). The “Richard Scarry” quote from Tim Kreider is in The Busy Trap, New York Times (2013) and also inspired a nice cartoon by Tom the Dancing Bug (2014). My history of work material came from many places but one short book I recommend is The Working Life: The Promise and Betrayal of Modern Work (2000) by Joanne B. Ciulla. Notes from Overground by Tiresias is an amazing book, giving the account of an intelligent person’s life in commuter hell.

Chapter Two: Consumption

The idea that your consumption is someone else’s work and the business about a country’s GDP comes from Enlightenment 2.0. (2014) by Joseph Heath and perhaps also his earlier title Filthy Lucre (2009) which delivers in its promise to give “remedial economics for people on the left.” Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered (1973) by E.F. Schumacher is a core text of alternative economics. The prediction of a 15-hour work week comes from Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren (1930) by John Maynard Keynes, but I found it through How Much is Enough?: Money and the Good Life (2012) by Robert and Edward Skidelsky. Bea Johnson’s blog can be found at zerowastehome.com. Enough: breaking free from the world of more (2008) by John Naish is a very inspiring book about living within one’s means. The Music of Chance (1990) is an absurdist novel by Paul Auster and contains all that wonderful stuff about debt, labour and thankless wall-building.

Chapter Three: Bureaucracy

The detail about “International Business Machines” comes from IBM and the Holocaust (2001) by Edwin Black. Green MP Caroline Lucas’ book is called Honourable Friends?: Parliament and the Fight for Change (2015) and is marvellous and must be read before parliament is reformed and it goes out of date!

Chapter 4: Our Stupid, Stupid Brains

The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) and Coming Up for Air (1939) by George Orwell are both essential reading for free thinkers; the former being a collection of journalism on working-class life, and the latter an absorbing novel about nostalgia and the present. Sartre’s idea of Bad Faith is articulated in Being and Nothingness (1943), which is barely readable and best avoided, perhaps in favour of his novel Nausea (1938). Roald Dahl discusses his life as a Royal Dutch Shell employee in his memoir Going Solo (1986). Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art is that neat little book about Resistance. David Cain’s wise essays can be read for free at Raptitude.com. Brian Dean’s great website lives at anxietyculture.com and he also wrote a nice article, “Escape Anxiety,” in New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009). Alain de Botton’s Status Anxiety (2004) is essential stuff, especially the “thesis” page and the Bohemia chapter. Mark Fisher’s essay is called “Suffering with a Smile” and appeared in The Occupied Times (2013). Tom Hodgkinson’s How to be Free (2006) is the most essential reading of all and his How To Be Idle (2004) and Brave Old World (2011) are good too. Musings on the prisoner’s dilemma comes from Andrew Potter and Joseph Heath’s The Rebel Sell (2004).

Chapter 5: The Good Life

The Kama Sutra is an ancient Indian text on the good life, a goodly portion of which is dedicated to rutting. Lin Yutang is the writer of, among other works, The Importance of Living (1937), which is highly readable and worth your time. Much has been written on Eudaimonia and the core texts are probably Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Eudemian Ethics. The stuff about consumers versus appreciators comes from Happiness: A Very Short Introduction by Daniel M. Haybron (2014). Palliative nurse Bronnie Ware’s Regrets of the Dying is a blog post from 2009. For more on Epicurus I refer you again to Status Anxiety (2004) by Alain de Botton. For more on the Stoics try A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy (2009) by William B. Irvine. I make brief reference in this chapter to The Urban Bestiary: Encountering the Everyday Wild (2009) by Lyanda Lynn Haupt, The Cloudspotter’s Guide (2006) by Gavin Pretor-Pinney, both of which are worth a look, and Look Up Glasgow (2013) by Adrian Searle. For books to get you excited about astronomy, you can’t go wrong with Cosmos (1980) by Carl Sagan or some of the amateur astronomy introductions by Patrick Moore. I make passing reference to The Fruit Hunters (2008) by Adam Gollner. “The last piece of chocolate in the universe” is the idea of my child self but something similar apparently appears in Savor (2015) by Niequist Shauna. I make an incorrect claim that the 10,000 rule comes from Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point (2000) when in fact it comes from the same author’s Outliers (2008).

Chapter 6: How Escapologists Use Their Freedom

The crab anecdote comes from an extremely charming work of naturalism and neurology called The Soul of an Octopus (2015) by Sy Montgomery. The quote about Wall Street and toilet cleaning comes from Vagabonding (2002) by Rolf Potts, which is worth reading if you ignore the garbage about working for one’s happiness. The Oscar Wilde quote about “the perfection of the soul within” comes from his essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism (1891). Tom Hodgkinson’s New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009). The concept of “Filling the Void” is well-trodden territory but that phrasing of the problem comes from The 4-Hour Work Week (2007) by Tim Ferriss. The Voyage of the Beagle (1839) is Charles Darwin’s account of his five-year voyage around the world and is surprisingly readable for its age and highly likable.

Chapter 7: A Montreal Year

“That Will Do” is what Houdini said to the McGill University student who punched him repeatedly in the stomach just before he died, a fact that comes from the Houdini biography referenced in the introduction section above. Much wisdom can be found in A Philosophy of Walking (2014) by Frédéric Gros as well as The Lost Art of Walking (2008) by Geoff Nicholson. For approachable natural history, try anything by Gerald Durrell, Leonard Dubkin ad Lyanda Lynn Haupt. Passing reference is made to Robinson Crusoe (1719) by Daniel Defoe and I’d also recommend a novel about it’s author Foe (1986) by J. M. Coetzee. If you’re interested in eating your way to immortality, Fantastic Voyage (2004) by Ray Kurzweil and Terry Grossman is the go-to text albeit a little old.

Chapter 8: Preparation

The quotation from Charles Simic (not Simi – a typo I had nothing to do with) comes from The Monster Loves His Labyrinth: Notebooks (2008). “I never hear the word ‘escape'” is a poem by Emily Dickinson and can be found, strangely enough, in The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. The details about Robert Graves’ assertion that there’s no money in poetry comes from Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900-1939 (2002) by Virginia Nicholson which is essential to read if you’re interested in Bohemian life, though I also refer briefly to his memoir Goodbye to All That (1929). An account of Alexander Supertramp’s life can be found in Into the Wild (1997) by Jon Krakauer. Dandelion Wine (1957) is a lovely if a tad bucolic novel by Ray Bradbury, a quote from which appears in New Escapologist Issue 1. The cancer diaries referred to belong to the library of a hospice I worked in.

Chapter 9: Escape Work

Arbeit macht frei means “work sets you free” and appears in the ironwork gates at the Auschwitz work/death camp, a fact I first learned from If This Is a Man (1947) by Primo Levi. Jacob Lund Fisker’s book is called Early Retirement Extreme (2010) and evolved from his blog of the same name. I make passing reference to an item from The Onion (2015) and another, The Strange and Curious Tale of the Last True Hermit, from GQ magazine (2014). Rob West’s blog charting the progress of his house-building project in British Columbia is called The Hand-Crafted Life. Ben Law’s core work on traditional house-building techniques is called Woodland Craft (2015) and Mark Boyle’s “Moneyless Man” column (2009-10) is archived at the Guardian website. Nicolette Stewart’s item about tiny homes can be found in New Escapologist Issue 8. Walden: Or, Life in the Woods (1854) by Henry David Thoreau is the obvious starting point for anyone considering a life in the woods near their mum’s house. Montreal Martin’s blog is called Things I Find in the Garbage. The interview with Michael Palin referred to is in Idler 37 (2006); I’m in it too, albeit under the wrong name, with a cover story called “Death to Professionalism”. How to Avoid Work (1949) by William J. Reilly is a witty and tricky-to-find-in-shops postwar career manual. Wringham’s escape plan first appeared in New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009).

Chapter 10: Escape Consumption

Mr Money Mustache has a blog of that very name. Diogenes of Sinope can be encountered in Diogenes of Sinope – The Man in the Tub (2013). Some of the practicalities of minimalism were first printed in New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009). Joshua Glenn’s The Wage Slave’s Glossary (2011) is an electric little book and is in fact a sequel to his The Idler’s Glossary (2008).

Chapter 11: Escape Bureaucracy

Roderick Long’s “delusional street person” comes from Just Ignore Them (2004) in Strike at the Root. La Boétie wrote Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (1576) which I came across in the dazzling How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in one question and twenty attempts at an answer (2010) by Sarah Bakewell. Kafka’s The Trial (1925) is the go-to work of fiction for bureaucratic absurdity. Narnia and Bas-Lag are the worlds of C. S. Lewis and China Mieville respectively. I don’t recall where I read about Chiune Sugihara but there’s a nice item about him in the Japan Times (2015). The Pomodoro Technique (2006) is a cute but effective productivity system concocted by Francesco Cirillo.

Chapter 12: Escape from our Stupid, Stupid Brains

Naked Stephen Gough’s point about being good comes from a Guardian (2012) item. The stuff about fear of flying versus rationalism comes from Risk: The Science and Politics of Fear (2008) Dan Gardener. The mags I recommend for longform journalism are The New Yorker, Jacobin and Aeon. Much of my info on the Bohemians of history is from Among the Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900-1939 (2003) by Virginia Nicholson. Caitlin Doughty is mentioned, whose first book is Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematorium (2014). The Wise Space Baby was originally mentioned in New Escapologist Issue 10 (2014), and the “damning conclusions” drawn by astronauts on the international space station are alluded to in An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth (2013) by Chris Hadfield. The Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale (1967) is a real thing and can be seen on Wikipedia. The stuff about Quat leaves comes from The Devil’s Cup: A History of the World According to Coffee (1999) by Stewart Lee Allen.

Chapter 13: The Post-Escape Life

Henry Miller’s list can be seen in Henry Miller on Writing (1964).

Epigrams

“Love laughs at locksmiths,” comes from a signed photograph of Houdini but has an older origin, featuring on an 1805 satirical print held by the British Museum. The other Houdini epigrams come from Handcuff Secrets (1907), Magical Rope Ties And Escapes (1920), Miracle Mongers and Their Methods (1920), Houdini’s Paper Magic: The Whole Art of Performing with Paper (1922).

★ Escape Everything! by Robert Wringham is available in libraries and was commercially re-released in paperback as I’m Out: How to Make an Exit.

Working Less: What wouldn’t it solve?

What does working less actually solve, I was asked recently. I’d rather turn the question around: is there anything that working less does not solve?

This is a really great article by Rutger Bretman. Thanks to reader Jonathan for bringing it to our attention.

It doesn’t have to be this way. We have the ability to cut a big chunk off our working week. Not only would it make all of society a whole lot healthier, it would also put an end to untold piles of pointless and even downright harmful tasks.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

Universal Basic Income

The idea of a universal basic income is about to leap from the margins to the mainstream, bringing promises of a happier and healthier population.

Today’s Guardian publishes very positive article by John Harris, summing up the rising tide of interest in Citizen’s Income.

The positive consequences extend into the distance: women are newly financially independent and able to exit abusive relationships, public health is noticeably improved, and people are able to devote the time to caring that an ever-ageing society increasingly demands. All the political parties are signed up: just as the welfare state underpinned the 20th century, so this new idea defines the 21st.

And to anyone who can get to London on May 8th, there’s this interesting-looking CI event at Conway Hall.

[A] big theme […] is that of automation, and its effects on the place of work in our lives. A third of jobs in UK retail are forecast to go by 2025. The Financial Times recently reported on research predicting that 114,000 jobs in British legal sector would be automated over the next 20 years.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

Inky

An octopus has made a brazen escape from the national aquarium in New Zealand by breaking out of its tank, slithering down a 50-metre drainpipe and disappearing into the sea.

We’re awfully fond of octopuses here at New Escapologist, admiring them for precisely this kind of stunt. They have the wit and flexibility that so many humans lack, which is why we put one on our homepage.

So it’s with much delight that we congratulate Inky on his Shawshank-style escape. Eight cheers for inky.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

Trailer

I made a promotional video for the book!

It’s one part A Clockwork Orange trailer to two parts MS PowerPoint.

Hope you like it! Be sure to turn the speakers on.

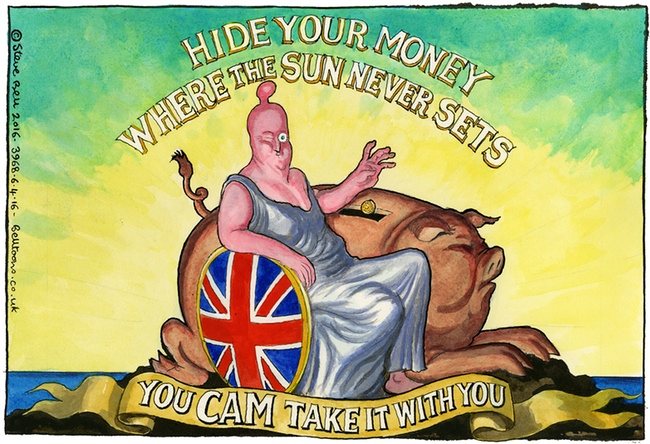

How to Avoid Tax Properly

In the wake of the Panama Papers I’d like to offer some advice to The Elite.

There are far easier ways to avoid paying tax than what you lot get up to. Why trouble yourself and sully your reputation over complicated offshore affairs when you could simply work less?

I join the nation in calling for the Prime Minister’s resignation, but unlike the nation I have the PM’s best interests at heart.

In the UK, as a politician of all people should know, you can earn as much as £11,000 before you’re asked to pay anything to the tax office. That’s plenty to live on, so stop earning, silly. Millions of people earn far less without the motivation of tax avoidance!

Bertrand Russell observed this long ago: “In view of the fact that the bulk of the public expenditure of most civilized Governments consists in payment for past wars or preparation for future wars, the man who lends his money to a Government is in the same position as the bad men in Shakespeare who hire murderers. The net result of the man’s economical habits is to increase the armed forces of the State to which he lends his savings. Obviously it would be better if he spent the money, even if he spent it in drink or gambling.”

Unfortunately, if you’re serious about this, there’s also consumption tax (that’s VAT here in the UK) to avoid. This means ceasing to buy so much stuff. This is called minimalism or voluntary simplicity. Historically, it’s been seen as a highly virtuous way to live.

You can still do your civic duty by paying at least some consumption tax–perhaps on groceries and other noshable goods–and by paying your council or municipal tax. I love to pay my council tax because it funds the things I like and things that benefit the community instead of the central government and those armed forces and bombs. £140 a month (between two!) for clean water, sewage removal, garbage and litter collection, schools, libraries and parks is a bargain. Moreover, when you work less you’ll really get the most out of those things.

My advice to the tax-dodging rich is to get real and do it properly with your reputation intact. Stop working. Nobody will miss you. Retire with dignity to a nice cottage with a view somewhere and write your memoirs. Quietly. Maybe your book could be called How I learned to stop swindling the nation and love to loaf.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

At least some autonomy

In his brilliant and demented new book, Being a Beast, Charles Foster writes:

The fact that we have at least some autonomy is awesome and intimidating. We’re used to thinking that autonomy is most critically on trial in dramatic, occasional situations — such as choosing the right to assisted suicide. But surely it’s the day-to-day choices that are the most terrifying and repercussive. Listen: you can choose whether to get up early, run round a field, have a cold bath and then read Middlemarch. Or stay in bed and watch Shopping TV. That’s astonishing. I can never get over it.

This is Escapological. It’s amazing that we can choose left or right all on our own, that this is simply part of our inheritance of evolution. It’s even crazier that we don’t appreciate it in the quotidian way he describes. I think it’s part of what keeps us going to work and ironing shirts instead of doing interesting things like, as in Foster’s case, digging a hole and living as a badger.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.