A Single Tiny Lid

Here’s a bit from a Charlie Brooker column 17 years ago. Still funny.

Happy Monday.

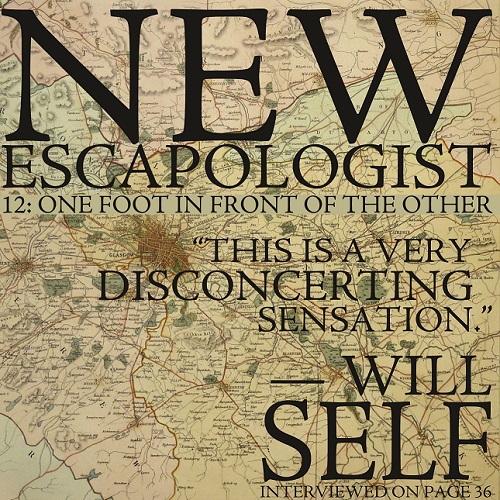

★ Join the mailing list today for a FREE PDF of Issue 12 featuring Will Self.

UBI roundup

Last weekend’s referendum saw UBI democratically rejected in Switzerland. The people’s choice! Offered Utopia, they don’t want it.

Actually, it’s not that simple. UBI (Citizen’s Income) is a huge idea and is competing with the deeply-ingrained Protestant work ethic. We may need to destroy work worship before (or at least in tandem) with a successful UBI campaign. It’s also expensive and nobody’s quite crunched the numbers convincingly yet, despite noble efforts.

A decent summary of the current state of play in the Guardian is sympathetic to UBI but says the next round of campaigning must be stronger in its numbers.

Before it can be seriously considered for a manifesto, further cost-saving compromises – such as restrictions for citizens who already receive a state pension – may need to be considered. The trick, then, as so often in progressive politics, will be to dream big, and then proceed with care.

Meanwhile, the Economist published a largely superb piece summing up the situation.

Both supporters and critics agree that universal basic incomes would challenge the centrality of paid work to the way people live.

I read it looking for a good argument against UBI but the ones present were a bit flimsy. For instance, the concern that the world would become filled by pointless ice cream parlours as a result of a new play ethic:

Hans Peter Rubi, a 64-year-old in the small town of Olten […] was given a pension of SFr2,600 on being sent into early retirement, and became an entrepreneur. He has used his pension to start an exotic ice-cream parlour. The avocado ice cream is proving difficult to perfect, and the innovation of staying open through the winter has yet to pay off. He needs a good summer for the business to be profitable; but he can afford to fail. “My security now is that I have my basic income. It gives a security to take a basic challenge.” … In a world of universal basic incomes, it is possible that the streets would be lined with mostly empty ice-cream shops, as people used society’s largesse on projects no one really needs.

The dystopian image of streets empty of all but unfrequented ice cream parlours is a chilling one (no pun intended) and one I’ve thought of before, but I don’t think it would happen, at least not in any permanent way. Research shows that (a) most people wouldn’t stop working in normal jobs anyway and (b) after a period of too many of these leisure follies we’d realise the mistake and move onto the next big paradigm, be it idling or space travel.

So UBI was rejected in Switzerland but it really does feel like this is just the beginning of a huge international discussion. Back when we mentioned Srnicek and Williams’ book, Inventing the Future, I said “It feels like the cartridge is loaded” and I think that’s been born out. Mainstream political parties are discussing it now.

Speaking of booky-wooks, I highly recommend Utopia for Realists by UBI campaigner Rutger Bregman. His argument is mainly a pragamatic approach to UBI but he also sticks up for a 15-hour standard workweek and open borders. Weirdly, he and I got off to a bad start (I didn’t care for the first few pages because I disagree with the “nasty, brutish and short” progress argument and a naff quip about dishwashers being great) but I was soon caught up in his optimism and research-based reasoning. Good stuff.

Any old hoo, until we get UBI there’s Escapology. Break free! Run! Save yourselves!

★ Join the mailing list today for a FREE PDF of Issue 12 featuring Will Self.

Your Free Self

On June 15th, in an unprecedented act of generosity, we’ll be sending a free PDF of the most recent New Escapologist (Issue 12, featuring Will Self) to everyone on the Escapology mailing list.

Don’t miss out. Join the mailing list today to get our latest issue for free!

It Begins

Good news item about the rise of Universal Basic Income, the pending Swiss referendum (all eyes on Switzerland this weekend!) and the various pilot schemes due to go ahead in 2017:

Crucially, [UBI] is also an idea that seems to resonate across the wider public. A recent poll by Dalia Research found that 68% of people across all 28 EU member states said they would definitely or probably vote for a universal basic income initiative. Finland and the Netherlands have pilot projects in the pipeline.

This weekend the concept faces its first proper test of public opinion, as Switzerland votes on a proposal to introduce a national basic income.

Probably best to overlook this weird little (I suspect editorial) addition though:

In an increasingly digital economy, it would also provide a necessary injection of cash so people can afford to buy the apps and gadgets produced by the new robot workforce.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

It doesn’t even stink

On your “off” time, you’re checking your phone and working anyway, and, when you’re not, you’re giving The Man back the money you sold most of your life away to obtain.

This doesn’t come from some radical rag like New Escapologist, folks. It’s the closing remark of a review of Captain America: Civil War.

That we’re all cast asunder in a gigantic juicing mechanism may be the only conclusion a thinking person can draw after two hours and 27 minutes of wrinkle-free, sexless CGI bludgeoning but it’s a refreshingly honest thing to see printed in a national newspaper.

They’re bullying us. You can skip these films, but they will keep piling up, and you will be regarded as one of those weird people who still expects to enjoy your popular culture. It’s part of the corporatization of everything.

The review’s an interesting read beyond this, actually. The critic points out that the movie isn’t bad exactly but that it’s nothing–an empty cavity of corporate nowt–and that blockbusters haven’t always been so cold and empty. At least Indiana Jones, he says, “clearly liked sex” but Captain America and Company seem to live for “earnestly deployed pseudo-techno-jargon”.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

Print for a Pound

Issues One and Four are both classics. The first has an interview with Judith Levine and my Invitation to Escapology essay that started the whole thing off. The latter has a smashing article by Reggie C. King about Sartre’s and Flaubert’s tendencies to stay in bed for long stretches.

Anyway, I printed too many for our last zine fair and there are now some leftover copies haunting our apartment, making a mockery of our minimalist living space, so I’d like very much to give them away to you for a quid apiece. Get ’em while they’re hot! And cheap!

To buy them, simply visit the shop today and click the “Buy for £1” button you’ll see there.

Not a bad way to introduce a friend to New Escapologist.

All dough raised will go into the kitty to print Issue 13.

UPDATE: The discounted copies of Issue One are now sold out. Thanks for your support! Issue Four is still available for a quid though: get them while they last.

UPDATE 2: That’s the surplus stock all sold out. Thank you very much, everyone.

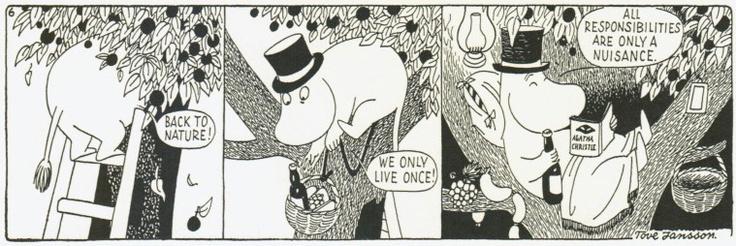

Saying It All in Three Panels

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

The They

Existentialists think that what makes humans different from all other beings is the fact that we can choose what to do. In fact, we must choose: the only thing we are not free to do is not to be free. Other entities have some predefined nature: a rock, a penknife or even a beetle just is what it is. But as a human, there is no blueprint for producing me. I may be influenced by biology, culture and personal background, but at each moment I am making myself up as I go along, depending on what I choose to do next. As Sartre put it: “There is no traced-out path to lead man to his salvation; he must constantly invent his own path. But, to invent it, he is free, responsible, without excuse, and every hope lies within him.” It is terrifying, but exhilarating.

From Think big, be free, have sex: ten reasons to be an existentialist.

However tough it is, existentialists generally strive to be “authentic”. They take this to mean being less self-deceiving, more decisive, more committed, and more willing to take on responsibility for the world.

Most of the time, we don’t do this very well. Why? For Heidegger, the fault lies with our bewitchment by a non-entity called das Man, often translated as “the they” – as in “they say it will all be over by Christmas” (or the “one” in the phrase “one doesn’t do that”). We can’t say who exactly this “they” is, but it is everywhere, and it steals the decisions I should be making by myself.

For Sartre, the problem is mauvaise foi, or bad faith. To avoid facing up to how free I am, I pretend not to be free at all.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

Bibliographed

I slightly regret not putting a bibliography in the back of Escape Everything! especially now that people have started asking why there isn’t one.

So by jove, I went back to the book and built a bibliography. Good job I have near-total recall when it comes to this sort of thing. It’s here. Happy to discuss the books and articles in the comments thread there.

★ Buy the brand-new Issue 12 of New Escapologist at the shop; buy our most popular digital bundle; or get the Escape Everything! book.

Escape Everything! The Missing Bibliography

A few people said Escape Everything! should have contained a bibliography. I’m sorry it didn’t. This was a bit of an oversight on my part. Since I’d usually name the book or article I was talking about in the main text, I didn’t immediately see a need for a bibliography. But this overlooked the usefulness of having them all in one place and missed the opportunity to talk about books, which is quite unlike me. So here it is: the missing bibliography. It’s thorough but not comprehensive, itemising the widest shoulders I stood on and pointing to further reading. Still, I hope it’s useful and fun. Most of the links go to Worldcat which can help you to find a local library copy. You can buy most of them in the usual places and I recommend Blackwell’s in particular. I’m also happy to discuss these books or provide extra information in the comments thread.

Introduction

The Houdini biography alluded to is The Secret Life of Houdini (2006) by Larry Sloman and William Kalush. Details on Lulu the vanishing pachyderm come from Hiding The Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible (2003) by Jim Steinmeyer. The quote from Adam Phillips comes from his book Houdini’s Box: On the Arts of Escape (2002). For some printed Simon Munnery, I recommend his little volume of aphorisms How to Live (2005) and my own history book about his early work You Are Nothing (2012). Grayson Perry wrote a good book called The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman (2011) and another called Playing to the Gallery (2014). Myles na Gopaleen is the Irish Times pseudonym of Brian O’Nolan (AKA Flann O’Brien), his finest peluche collected in The Best of Myles: A Selection from Cruiskeen Lawn (1968).

Chapter One: Work

Bob Black’s wisdom comes from his essay The Abolition of Work (1985) and is essential reading. The Buckminster Fuller quote comes from an article in New York magazine (1970). David Graeber’s popular essay On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs comes from Strike! Magazine (2013). The “Richard Scarry” quote from Tim Kreider is in The Busy Trap, New York Times (2013) and also inspired a nice cartoon by Tom the Dancing Bug (2014). My history of work material came from many places but one short book I recommend is The Working Life: The Promise and Betrayal of Modern Work (2000) by Joanne B. Ciulla. Notes from Overground by Tiresias is an amazing book, giving the account of an intelligent person’s life in commuter hell.

Chapter Two: Consumption

The idea that your consumption is someone else’s work and the business about a country’s GDP comes from Enlightenment 2.0. (2014) by Joseph Heath and perhaps also his earlier title Filthy Lucre (2009) which delivers in its promise to give “remedial economics for people on the left.” Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered (1973) by E.F. Schumacher is a core text of alternative economics. The prediction of a 15-hour work week comes from Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren (1930) by John Maynard Keynes, but I found it through How Much is Enough?: Money and the Good Life (2012) by Robert and Edward Skidelsky. Bea Johnson’s blog can be found at zerowastehome.com. Enough: breaking free from the world of more (2008) by John Naish is a very inspiring book about living within one’s means. The Music of Chance (1990) is an absurdist novel by Paul Auster and contains all that wonderful stuff about debt, labour and thankless wall-building.

Chapter Three: Bureaucracy

The detail about “International Business Machines” comes from IBM and the Holocaust (2001) by Edwin Black. Green MP Caroline Lucas’ book is called Honourable Friends?: Parliament and the Fight for Change (2015) and is marvellous and must be read before parliament is reformed and it goes out of date!

Chapter 4: Our Stupid, Stupid Brains

The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) and Coming Up for Air (1939) by George Orwell are both essential reading for free thinkers; the former being a collection of journalism on working-class life, and the latter an absorbing novel about nostalgia and the present. Sartre’s idea of Bad Faith is articulated in Being and Nothingness (1943), which is barely readable and best avoided, perhaps in favour of his novel Nausea (1938). Roald Dahl discusses his life as a Royal Dutch Shell employee in his memoir Going Solo (1986). Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art is that neat little book about Resistance. David Cain’s wise essays can be read for free at Raptitude.com. Brian Dean’s great website lives at anxietyculture.com and he also wrote a nice article, “Escape Anxiety,” in New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009). Alain de Botton’s Status Anxiety (2004) is essential stuff, especially the “thesis” page and the Bohemia chapter. Mark Fisher’s essay is called “Suffering with a Smile” and appeared in The Occupied Times (2013). Tom Hodgkinson’s How to be Free (2006) is the most essential reading of all and his How To Be Idle (2004) and Brave Old World (2011) are good too. Musings on the prisoner’s dilemma comes from Andrew Potter and Joseph Heath’s The Rebel Sell (2004).

Chapter 5: The Good Life

The Kama Sutra is an ancient Indian text on the good life, a goodly portion of which is dedicated to rutting. Lin Yutang is the writer of, among other works, The Importance of Living (1937), which is highly readable and worth your time. Much has been written on Eudaimonia and the core texts are probably Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Eudemian Ethics. The stuff about consumers versus appreciators comes from Happiness: A Very Short Introduction by Daniel M. Haybron (2014). Palliative nurse Bronnie Ware’s Regrets of the Dying is a blog post from 2009. For more on Epicurus I refer you again to Status Anxiety (2004) by Alain de Botton. For more on the Stoics try A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy (2009) by William B. Irvine. I make brief reference in this chapter to The Urban Bestiary: Encountering the Everyday Wild (2009) by Lyanda Lynn Haupt, The Cloudspotter’s Guide (2006) by Gavin Pretor-Pinney, both of which are worth a look, and Look Up Glasgow (2013) by Adrian Searle. For books to get you excited about astronomy, you can’t go wrong with Cosmos (1980) by Carl Sagan or some of the amateur astronomy introductions by Patrick Moore. I make passing reference to The Fruit Hunters (2008) by Adam Gollner. “The last piece of chocolate in the universe” is the idea of my child self but something similar apparently appears in Savor (2015) by Niequist Shauna. I make an incorrect claim that the 10,000 rule comes from Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point (2000) when in fact it comes from the same author’s Outliers (2008).

Chapter 6: How Escapologists Use Their Freedom

The crab anecdote comes from an extremely charming work of naturalism and neurology called The Soul of an Octopus (2015) by Sy Montgomery. The quote about Wall Street and toilet cleaning comes from Vagabonding (2002) by Rolf Potts, which is worth reading if you ignore the garbage about working for one’s happiness. The Oscar Wilde quote about “the perfection of the soul within” comes from his essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism (1891). Tom Hodgkinson’s New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009). The concept of “Filling the Void” is well-trodden territory but that phrasing of the problem comes from The 4-Hour Work Week (2007) by Tim Ferriss. The Voyage of the Beagle (1839) is Charles Darwin’s account of his five-year voyage around the world and is surprisingly readable for its age and highly likable.

Chapter 7: A Montreal Year

“That Will Do” is what Houdini said to the McGill University student who punched him repeatedly in the stomach just before he died, a fact that comes from the Houdini biography referenced in the introduction section above. Much wisdom can be found in A Philosophy of Walking (2014) by Frédéric Gros as well as The Lost Art of Walking (2008) by Geoff Nicholson. For approachable natural history, try anything by Gerald Durrell, Leonard Dubkin ad Lyanda Lynn Haupt. Passing reference is made to Robinson Crusoe (1719) by Daniel Defoe and I’d also recommend a novel about it’s author Foe (1986) by J. M. Coetzee. If you’re interested in eating your way to immortality, Fantastic Voyage (2004) by Ray Kurzweil and Terry Grossman is the go-to text albeit a little old.

Chapter 8: Preparation

The quotation from Charles Simic (not Simi – a typo I had nothing to do with) comes from The Monster Loves His Labyrinth: Notebooks (2008). “I never hear the word ‘escape'” is a poem by Emily Dickinson and can be found, strangely enough, in The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. The details about Robert Graves’ assertion that there’s no money in poetry comes from Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900-1939 (2002) by Virginia Nicholson which is essential to read if you’re interested in Bohemian life, though I also refer briefly to his memoir Goodbye to All That (1929). An account of Alexander Supertramp’s life can be found in Into the Wild (1997) by Jon Krakauer. Dandelion Wine (1957) is a lovely if a tad bucolic novel by Ray Bradbury, a quote from which appears in New Escapologist Issue 1. The cancer diaries referred to belong to the library of a hospice I worked in.

Chapter 9: Escape Work

Arbeit macht frei means “work sets you free” and appears in the ironwork gates at the Auschwitz work/death camp, a fact I first learned from If This Is a Man (1947) by Primo Levi. Jacob Lund Fisker’s book is called Early Retirement Extreme (2010) and evolved from his blog of the same name. I make passing reference to an item from The Onion (2015) and another, The Strange and Curious Tale of the Last True Hermit, from GQ magazine (2014). Rob West’s blog charting the progress of his house-building project in British Columbia is called The Hand-Crafted Life. Ben Law’s core work on traditional house-building techniques is called Woodland Craft (2015) and Mark Boyle’s “Moneyless Man” column (2009-10) is archived at the Guardian website. Nicolette Stewart’s item about tiny homes can be found in New Escapologist Issue 8. Walden: Or, Life in the Woods (1854) by Henry David Thoreau is the obvious starting point for anyone considering a life in the woods near their mum’s house. Montreal Martin’s blog is called Things I Find in the Garbage. The interview with Michael Palin referred to is in Idler 37 (2006); I’m in it too, albeit under the wrong name, with a cover story called “Death to Professionalism”. How to Avoid Work (1949) by William J. Reilly is a witty and tricky-to-find-in-shops postwar career manual. Wringham’s escape plan first appeared in New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009).

Chapter 10: Escape Consumption

Mr Money Mustache has a blog of that very name. Diogenes of Sinope can be encountered in Diogenes of Sinope – The Man in the Tub (2013). Some of the practicalities of minimalism were first printed in New Escapologist Issue 3 (2009). Joshua Glenn’s The Wage Slave’s Glossary (2011) is an electric little book and is in fact a sequel to his The Idler’s Glossary (2008).

Chapter 11: Escape Bureaucracy

Roderick Long’s “delusional street person” comes from Just Ignore Them (2004) in Strike at the Root. La Boétie wrote Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (1576) which I came across in the dazzling How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in one question and twenty attempts at an answer (2010) by Sarah Bakewell. Kafka’s The Trial (1925) is the go-to work of fiction for bureaucratic absurdity. Narnia and Bas-Lag are the worlds of C. S. Lewis and China Mieville respectively. I don’t recall where I read about Chiune Sugihara but there’s a nice item about him in the Japan Times (2015). The Pomodoro Technique (2006) is a cute but effective productivity system concocted by Francesco Cirillo.

Chapter 12: Escape from our Stupid, Stupid Brains

Naked Stephen Gough’s point about being good comes from a Guardian (2012) item. The stuff about fear of flying versus rationalism comes from Risk: The Science and Politics of Fear (2008) Dan Gardener. The mags I recommend for longform journalism are The New Yorker, Jacobin and Aeon. Much of my info on the Bohemians of history is from Among the Among the Bohemians: Experiments in Living 1900-1939 (2003) by Virginia Nicholson. Caitlin Doughty is mentioned, whose first book is Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematorium (2014). The Wise Space Baby was originally mentioned in New Escapologist Issue 10 (2014), and the “damning conclusions” drawn by astronauts on the international space station are alluded to in An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth (2013) by Chris Hadfield. The Holmes and Rahe Stress Scale (1967) is a real thing and can be seen on Wikipedia. The stuff about Quat leaves comes from The Devil’s Cup: A History of the World According to Coffee (1999) by Stewart Lee Allen.

Chapter 13: The Post-Escape Life

Henry Miller’s list can be seen in Henry Miller on Writing (1964).

Epigrams

“Love laughs at locksmiths,” comes from a signed photograph of Houdini but has an older origin, featuring on an 1805 satirical print held by the British Museum. The other Houdini epigrams come from Handcuff Secrets (1907), Magical Rope Ties And Escapes (1920), Miracle Mongers and Their Methods (1920), Houdini’s Paper Magic: The Whole Art of Performing with Paper (1922).

★ Escape Everything! by Robert Wringham is available in libraries and was commercially re-released in paperback as I’m Out: How to Make an Exit.