All of Us or None

If you’re at all interested in prison reform or abolition, want to learn more or do something about the often-racist system of mass incarceration, Jenny Odell lists the following groups (via activist and Black prisoner Alfred Woodfox) in her recent book Saving Time:

Safe Alternatives to Segregation Initiative

I also found a group called Vera, which is where the shocking photograph above came from.

I’d also recommend (as reviewed in Issue 14) Criminal: How Our Prisons Are Failing Us All by Angela Kirwin and A Bit of a Stretch by Chris Atkins.

*

Morris Quarter

Every year, Freddie Yauner undertakes an “homage to William Morris from 1st January to 24th March (Morris’s birthday), where he attempts to ‘become’ William Morris whilst making new works.”

It’s an art project. He calls it his “Morris Quarter” — three months spent living under the guise and driven by the ethics of William Morris — which reminds me of a scene in Nathan Barley where a trendy magazine editor has an “Ape Hour.”

I do like the idea of trying to “become” someone else though, of living in homage so thoroughly. It offers a sort of escape. Escape the self, escape even this century, by living in a semi-delusional state for personal pleasure and for the common good.

“I begin my Morris quarter by rereading [Morris’] 1890 novel News from Nowhere,” he tells the Guardian, I read his other works, too, and try to build skill sets he had.”

I’ve had singing lessons to sing his socialist chants, made prints on his letter press in his house in Hammersmith, west London, and designed wallpaper based on the River Lea. Morris knew the river well and named one of his patterns after it. I’ve also made socialist flags in Leyton, east London, where his mum lived while Morris was at Oxford.

I have also learned embroidery from my mother and taught it to my children. Morris taught his daughter, May, to embroider, and she became one of the greatest craftspeople in Britain.

Eccentricity is good. In this case, it offers Yauner a self-made and good-humoured escape hatch into a life of collective-minded creativity.

*

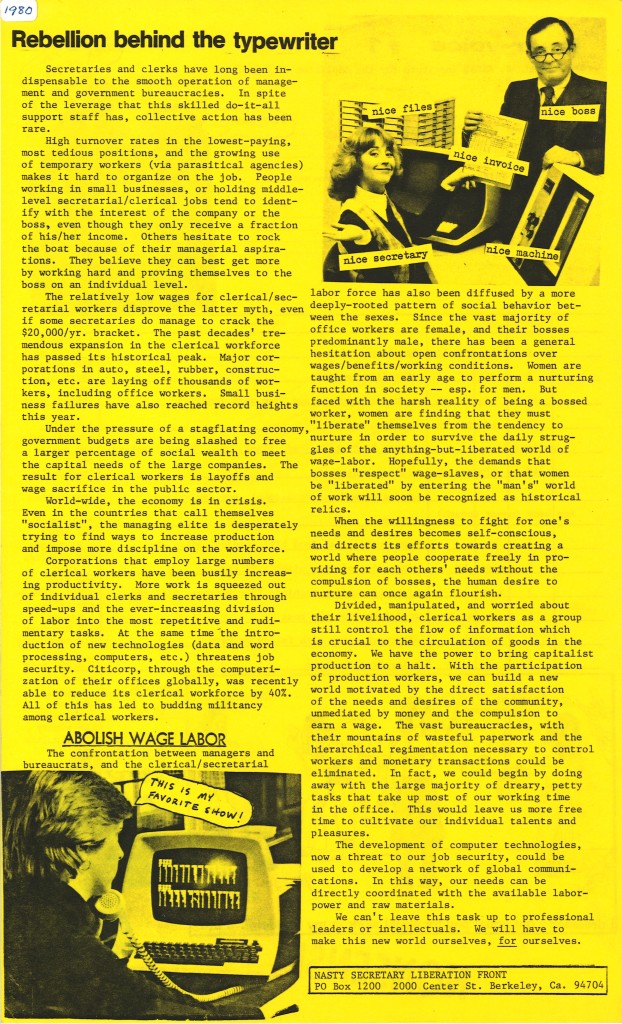

Rebellion Behind the Typewriter

Well, I said I wanted to find out more about the Nasty Secretary Liberation Front.

It turns out they were a precursor to Processed World magazine, a publication so shockingly similar to New Escapologist in spirit that you’d think we’d based New Escapologist on it. We didn’t. I found the archive of Processed World about four years ago and I’ve been meaning to do some sort of deep dive project on it ever since, though I am not yet sure how that will manifest itself.

The Nasty Secretaries were also known as the Union of Concerned Commies and the people behind it went directly on to form Processed World.

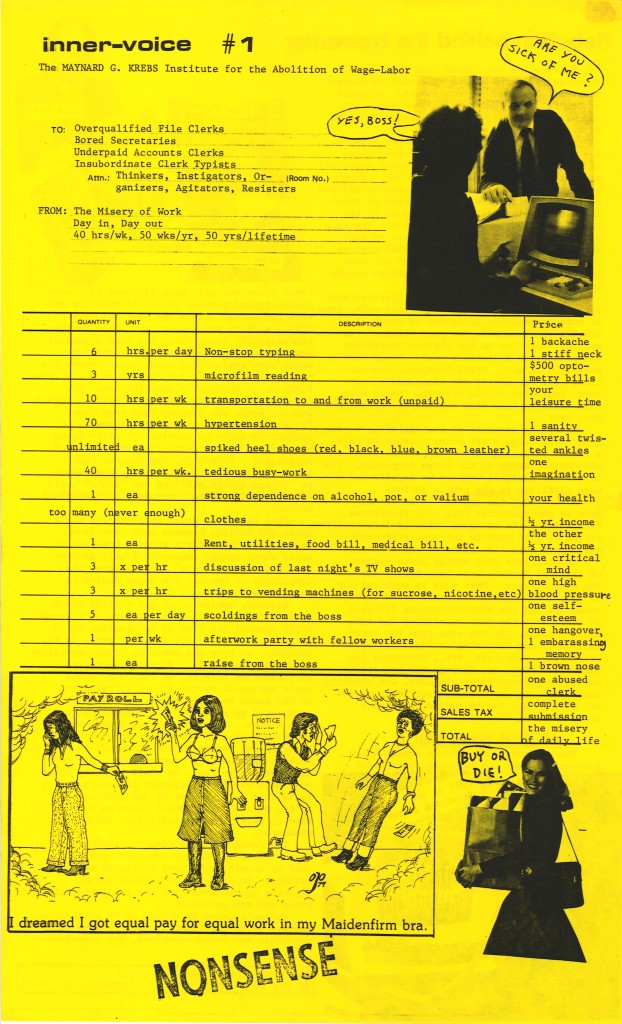

Their first publication (1980) was a single A4 sheet called Innvervoice #1, a pun on “invoice” and it details the costs of various things you have to do at work, almost Christie Malry-style.

There are many references to it online but it took some digging to actually find a scan of it. I found it via the Wayback Machine in the end, and here it is, for all to see, back on the actual Web:

You can click to make it a bit bigger if you want to.

The cost of “transportation to and from work (unpaid)” is “your leisure time”. The cost of a raise is “1 brown nose.”

I love the “nonsense” rubberstamp. I should have some of those made.

This is the reverse:

*

There have been no editions of Processed World since 2005. New Escapologist began in 2007. To help us continue into 2027, please subscribe or otherwise back our Kickstarter campaign here.

The Arbitrary Whim of Some Jerk Manager

Stomach hurt? Headaches? Nervous twitches appearing in odd places? Regular nightmares about work? You’ve caught it! STRESS!! The effects of stress can be quite far-reaching. Among the more fearsome results are heart disease, nervous system disorders, assorted inexplicable physical malfunctions, sometimes even dramatic pain.

This is from a leaflet circulated in the 1980s by a group called the “Nasty Secretaries Liberation Front” (and naturally, I want to find out far, far more about them).

The text of the leaflet was transcribed and uploaded to libcom.org (“a resource for everyone fighting to improve their lives, communities and working conditions.”)

Everything about it is remarkable, correct, and ahead of its time:

When you “get” stress, have you caught something? Or is it more accurate to say that we are all caught by situations which force us to put up with ridiculous and humiliating demands, as often as not simply to fulfil the arbitrary whim of some jerk manager?

Stress is not a result of individual failings. It is the result of an irrational and inhumane society. The solution to stress will not be found in any special seminar, or in any special meditation or exercise techniques (though it is true that some such techniques help some people temporarily cope with some results of stress). Stress is such a fundamental part of contemporary society that it will take a deliberate restructuring of the social order to reduce it in any real sense.

*

If you’d like to vent about workplace stress, why not submit a Workplace Woe to New Escapologist. To read the woes of others — and escape-based solutions — subscribe now to New Escapologist in print or digital formats.

Refusal

Bartleby (1853):

I would prefer not to.

Anthropologist Carole McGranahan on refusal (2016):

To refuse is to say no, but, no, it is not just that. To refuse can be generative and strategic. A deliberate move toward one thing, belief, practice, or community and away from another. Refusal illuminates limits and possibilities, especially but not only of the state and other institutions.

Jenny Odell in Saving Time (2023):

Refusal may start in you but cannot end in you. It must be spoken, in messages, in magazines, in forums, and off-hours, in an ongoing “reehearsal.” In summoning a world, it is the most creative thing you could possibly do.

*

Refuse all but the ability to escape! Subscribe to our magazine of refusal by Kickstarter today.

4 x 4

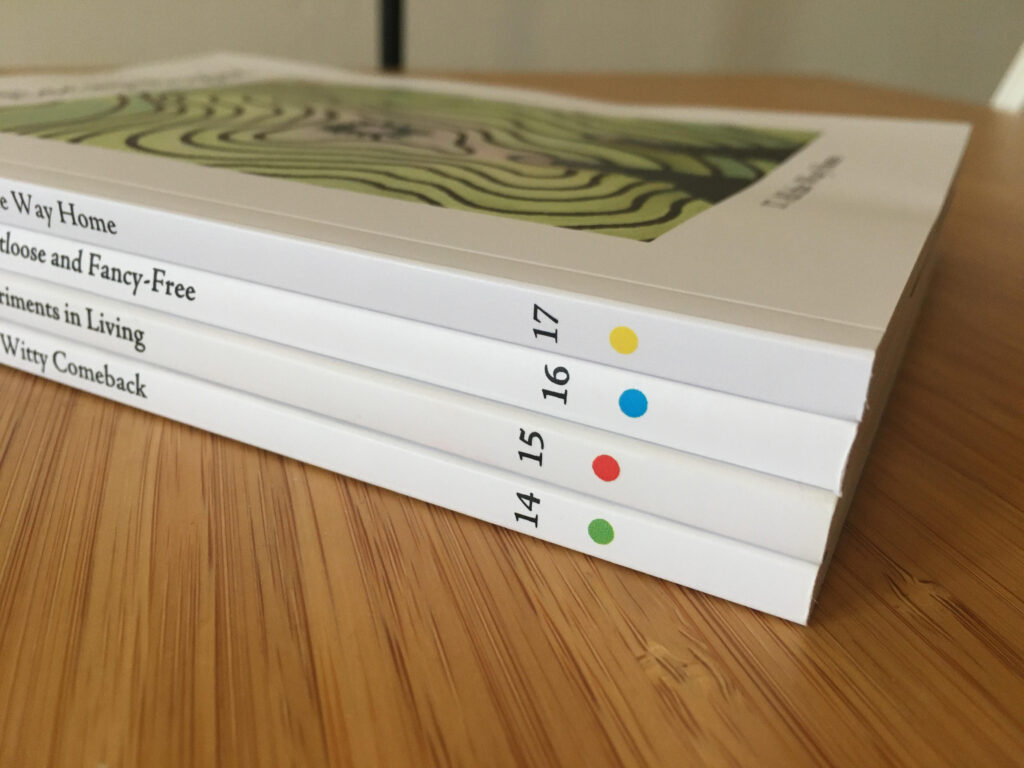

A reader emailed to check which issues he’d already received after backing the 2023 Kickstarter and which ones are coming next. Thank you for asking.

Just so there’s no confusion:

Issues 14-17 were the ones we Kickstarted in 2023. They were all published and shipped as promised. The print editions of those issues are now largely sold out. (Digital versions are still available).

Issues 18-21 are the ones we’re Kickstarting now. Here’s where to go if you’d like to hear the happy “plop!” of a new edition hitting your doormat twice a year.

New Escapologist will return in late November 2025 with Issue 18: The Time of Your Life.

Making the Transition

Highwire artist Philippe Petite, who crossed the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre in 1973, says:

Once I’m on the wire it’s alright. It’s the moment of transition from the solidity building to the wire that’s frightening.

I’ve written about Petite before because I love the documentary Man on Wire (2008). The above quote is from the drama film The Walk (2015), which means the quote came from a fictional version of Petite. Maybe it has basis in reality, maybe it doesn’t. I am not above quoting from fictional people.

In any event, it contains wisdom. Take it from me that once you’re out there — away from a secure income, in the wilds — all is well. It’s the trepidation that’s the kicker.

I was thinking about this today I tried to write something substantial for the first time since recovering. It felt scary until I got started. The only hump to get over was beginning. Once I got started, I was in full swing. Whatever it is, just start. Make a mess of it. Then make it better. Then you’ll find flow. “Look, ma, no hands!”

*

Please subscribe to New Escapologist by backing our Kickstarter campaign. w00p!

Zombie Sighting

Gabriel Josipovici’s pandemic-era diary and essay collection, 100 Days, is full of wisdom, wit, and rage. But look at this:

F, many years ago [asks me] ‘why do you lay the table for breakfast the evening before? You might want quite different food or no breakfast at all.’ I try to explain that when I come downstairs to make breakfast, I don’t really want to have to think, just to make it automatically, since I don’t feel properly awake til I’ve had my cup of tea.

I am vindicated! He harnesses the zombie!

*

Please subscribe to New Escapologist by backing our Kickstarter campaign. w00p!

The Unthinking Steps

There are seven flights of steps up to our flat: six main ones plus the one that takes you up to the main staircase from the ground level. I call that first flight “the unthinking steps.”

Basically, I find the ascent of the stairs really boring. There are small things I can do to alleviate the boredom, such as fishing the door keys out of my pocket, but there aren’t enough of these small things to occupy my mind all the way to the top.

So instead of squandering my “entertainment” on that very first flight, I try to empty my head of thoughts completely. It’s a little exercise in mindlessness.

It doesn’t always work. Once I’m in the building, I start thinking automatically about the things I’ll do once I’m home. But I try to quash that automatic process for the few seconds that it takes to climb the unthinking stairs.

The idea is to survive the boredom of the repetitive ascent up the stairs. But it’s also to slow down, to stop planning or letting the mind fly too soon into the future.

Do you have an unthinking stairs or similar?

*

Ennui

By “the problem of leisure,” Stuart Whatley in the New Statesman (a generally left-wing periodical) refers to the idea that most people wouldn’t know how to spend their time if they no longer had to go to work. Or, worse, that they would spend it deleteriously. It’s the “lotus-eater” theory in which we all become the obese layabouts of WALL-E. I’ve always found this to be a deeply conservative and patronising position. My position is that, after a period of idling, most people will want to act, to help themselves and the world in some way. But what if I’m wrong?

Over a decade of writing and thinking about modern work and its opportunity costs, I have generally mentioned the “problem of leisure” only in passing, largely because I would like to believe that it is soluble. Yet the political situation in the United States (and some other industrialised democracies) demands a reckoning, and it cannot be understood without reference to misspent leisure.

Whatley worries, basically, that the nihilistic politics that led to Trump and Vance in the US (and to Starmer and, perhaps inevitably, a PM Farage in the UK) and to an inward-looking rejection of optimistic internationalism, was caused by an ennui inherent to increased and misspent leisure time coupled with a lack of interest in boring or bullshitty work.

I’d argue that leisure time isn’t increasing, not in recent years anyway. It increased over the 20th Century for sure, thanks to well-organised labour movements, but we’re in the gig economy now, where, for many, every hour has some small cash value and must be hungrily seized upon as a matter of survival. I can’t deny, however, the sort of alienation from work he describes seems to be increasing (it’s certainly why I wanted to escape) and the likelihood that some people fall into a Leisure Trap of “an endless stream of video content or chocolate cake or edibles or any other indulgence cannot deliver lasting satisfaction. Everything gets old eventually, leaving one to grope around for the next fix.”

It’s the reason, I think, that there was no post-pandemic cultural renaissance comparable to the last century’s interwar years. We didn’t have it bad enough in the pandemic. Netflix and YouTube made it just about acceptable to be stuck indoors all the time. Some people even preferred life that way. I’m forced to accept that the ennui Whatley speaks of probably exists.

And yet he does not give up on my sort of optimism:

Yet solutions to the problem of leisure exist throughout our own wisdom tradition, which stresses the value of friendship (Epicurus), contemplation (Aristotle), and “other-regarding” public service (Cicero). These basic human goods have been severely eroded, producing an age of loneliness, inattention, and ginned-up tribalism; but each could be reclaimed with sufficient free time and a proper command over it. While there will always be demagogues, conspiracists, and cult leaders, they would have no purchase over a people who can find fulfilment in themselves.

*