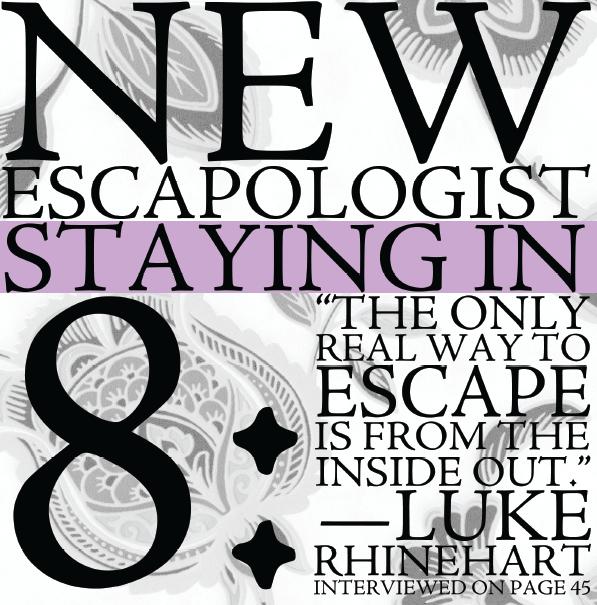

New Escapologist Issue Eight out now!

Just completed before the year is out! Available, as usual, in print and PDF at the shop.

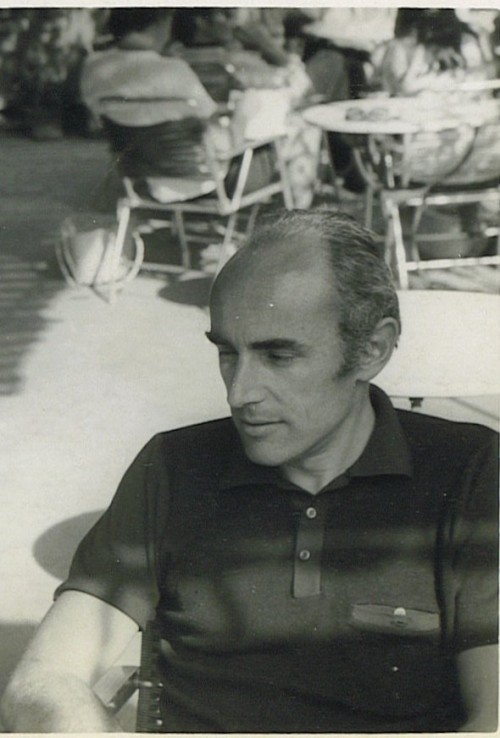

This issue features a very special interview with Dice Man author Luke Rhinehart.

Subscriber and pre-order copies will be shipped this week.

Dice Man interview

We can now announce the Issue Eight big interview. It’s surely our most exciting to date.

Ladies and Gentlemen, it’s the writer of The Dice Man: Luke Rhinehart.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount today.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Reggie and Aislinn for Christmas

Our friends and regular New Escapologist contributors, Reggie C. King and Aislínn Clarke, are the masterminds behind Wireless Mystery Theatre.

Anyone who came to our Issue 6 launch party in Edinburgh last year will already have experienced their splendor.

A couple of weeks ago, WMT played to a thousand-strong audience at the Ulster Hall in Belfast. The show, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, was broadcast live on BBC Radio.

What better way to spend an hour of Christmas Eve than with this performance? Enjoy the show for free on the BBC iPlayer.

Congratulations are due to the WMT. It’s quite a thing.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount today.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Flitcraft

In The Maltese Falcon, there’s a digression in which Sam Spade tells the story of Charles Flitcraft.

It illustrates a good part of the appeal of Absurdity to the Escapologist: the fact that you really can just walk away if you choose to.

Flitcraft is a modestly successful estate agent who, after narrowly missing being killed by a falling piece of masonry, decides to walk out on his life.

Flitcraft had been a good citizen and a good husband and father, not by any outer compulsion, but simply because he was a man most comfortable in step with his surroundings. He had been raised that way. The people he knew were like that. The life he knew was a clean orderly sane responsible affair. Now a falling beam had shown him that life was fundamentally none of these things. He, the good citizen-husband-father, could be wiped out between office and restaurant by the accident of a falling beam. He knew then that men died at haphazard like that, and lived only while blind chance spared them.

I came to Flitcraft via Oracle Night by Paul Auster, which includes a brief examination of the character and an expanded exploration of the idea.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount today.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Coquettish

A sneak peek at something special.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount today.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

The Lavender Hill Mob

Instead of changing as usual at Charing Cross, I came straight on to Rio de Janeiro. — Henry Holland

I just saw The Lavender Hill Mob for the first time. I wish I’d seen it years ago. It had moments of such comic and existential beauty that I found myself wanting to cry. Watch it!

The film tells the story of Henry Holland (Alec Guinness): a bowler-hatted bank employee who daily supervises the minting of millions while waiting on a pay cheque. “I was a potential millionaire,” he says, “yet I had to be satisfied with eight pounds, fifteen shillings, less deductions”.

He eventually finds the missing piece in his plan to steal a million pounds’ worth of gold doubloons with the idea that he might flee to a life of leisure in Rio.

It’s quite the Escapological film. Some notes about that:

1. Even though the film is about a crime, there’s no doubt in our minds that it’s a morally-justified act. We know that Holland is right to steal the money because his alternative fate — a life of undignified, repetitive servitude — is unthinkable. We’re on Holland’s side immediately. This is because the world loathes the rat race. Holland has already essentially paid for his crime through twenty years of toil. Morally, he’s practically owed the money.

2. More than the money, his Great Escape is a matter of personal respect, of taking control for once, and of reclaiming his lost dignity. Sound familiar? And to the extent that money is part of the heist, it is as a means rather than an end.

3. There are moments of poetry in which tokens of Henry’s formerly dreary life ironically become his salvation. Towards the end of the film, he is able to elude the police by merging into a crowd of anonymous, identically-dressed London commuters. Likewise, the gold is smuggled into Paris by molding it into souvenir Eiffel Tower models: the very junk objects which kept Holland’s partner in servitude for so long.

4. There are moments of brotherly recognition between the two men that they’re doing something sensational: launching a self-hatched scheme, their own system-beating escape plan finally coming to fruition. There is nothing in the world so exciting.

And it’s all done with well-dressed, softly-spoken, gentlemanly decorum.

*

Our Issue 8 appeal has just about succeeded. Huge thanks to everyone who bought print issues, PDF packages, or pre-ordered their Issue Eights. We now have enough money to print the issue. Huzzah! Alas, about 10% of this sum comes from shipping charges, so we’ve not quite broken even on the scheme yet. Do consider helping us if you’ve not already.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount today.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Defaulting

In relation to our recent post about peer pressure and living within a certain expected mode, our Eudaemonology editor Neil sends us this.

The career you end up working in depends chiefly on what you saw as options when you were just starting to enter the workforce. That was a very narrow period of time, during which you were only aware of a limited number of options. You went with whatever made sense at that time. The result — what you do today — is more or less happenstance.

Friends too, are mostly in our lives as defaults. Most of us have found some incredible and inspiring people just by letting happenstance deliver them, but once we have some stable friendships we become complacent and stop actively looking for friends that really resonate with our values and interests, if we ever did at all.

Unless we take the bull by the horns, we end up as products of destiny rather than masters of it. Not saying that’s a bad thing but it does raise the question of how much free will we really have. Again.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount today.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

Agency

Something that came up in this book with regards to “the pressure to consume” is that affluent people in certain social or professional circles expect a certain standard of living. Even when they know that the tokens of this standard has ill effects financially, ecologically, or psychologically, they will persist in the pursuit of them.

If lawyers, for example, are supposed to drive SUVs, then you — as a lawyer — have to drive one too. If university lecturers must be surrounded by books, then you — as a young academic — must start building your expensive private library post-haste. It’s not the innate function or beauty of SUVs or books to which you’re attracted, but the social mobility (or at least in-group access) that you perceive to come with it.

In the book, some sound top-down political measures are offered as ways of curbing this problem: forcing a reduction in advertising; making it harder for advertisers to manipulate the instinct to keep up with the Joneses; introducing certain kinds of consumption tax. Sensible suggestions but my inner psychologist remains concerned by the root of the problem:

Don’t these people have agency in the world? Are they really so manipulated by advertising or peer pressure that they’re unable to resist the tractor beam of want? Don’t they have a smattering of free will or ability to go against the grain? Is the fear of difference, of appearing marginally eccentric, really so great?

The alternative to keeping up with the Joneses is not to swing to the other extreme. Nobody is asking you to live on the street or walk absolutely everywhere or to wear hair shirts. Be the lawyer who cycles to work. Be the minimalist academic. Your peers will not reject you. You might even stand out as someone who has integrity, who ploughs her own furrow. You might even be admired for being different.

As one who prefers to grant the benefit of the doubt, I don’t like to think that so many people (educated professionals at that) are so stupid or weak that they would crumble so easily in the face of peer pressure. But that’s dangerously close to the Ad Man’s defense: “maybe we do encourage people to buy pointless tat, but they don’t have to listen to us. People are free to make their own decisions”.

But are they?

*

Big thanks to everyone who has already responded to our Issue Eight request. We’re not quite in the green light zone yet but we’re inching ever closer. Do consider helping us if you’ve not already.

Issue Eight: your help

Issue Eight is almost ready to go! It looks to be another hundred-page monster.

The theme of the issue is Staying In and we’ve got articles about such homey matters as cottage industry, tea, pajamas, food, integrity, home music production, art collecting, cigars, thought, John Cowper Powys, an interview with artist Ellie Harrison, loads of great artwork, Dickon Edwards, alternative dwellings, BBC Radio’s Steven Rainey, Reggie C. King, and an ominously hanging ‘more…’.

You may have noticed that this release is hot on the heels of Issue Seven, which was released only a month ago. Four to six months is the usual gap between our issues, so this is a startlingly productive event for us.

But this presents a problem. The usual time gap allows the current issue to fund production of the next one. That’s our business model: we’ve never applied for a grant (which would likely compromise our content) or attempted to make money with advertising (which would definitely compromise our content, not to mention our principles) and we’re not in debt (which is rare for an indie magazine project).

Rather than resorting to those strategies or to launching an undignified and labour-intensive Kickstarter or IndieGoGo campaign, I’d ask you all to do one of the following things as soon as possible:

– preorder a copy of Issue Eight in print (£6) or PDF (£5)

– buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.

– Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount

– buy a copy of Issue Seven if you’ve not already done so

– buy a back issue

– take out a subscription (your existing subscription may need updating after Issue Eight anyway)

None of this is without reward. You’ll be receiving top-notch New Escapologist content for your hard-earned scratch. We’re not asking for donations or offering alternative rewards of dubious quality. I’m just asking you to do your shopping now so that we can get the wheels of production back into action as soon as possible.

Let’s get another New Escapologist into the world before the end of 2012!

And with Christmas and Hanukkah and Yule coming up, you could even buy an escape plan for a pal.

Thank you in advance,

Robert Wringham

Editor, New Escapologist

How Much is Enough?

Are we then suggesting a return to the living standards of 1974? Not necessarily, for the luxuries acquired since then may, even if they have added nothing to our real well-being, be painful to forego. (This is an instance of the general truth that damaging social changes cannot always be rectified simply by being reversed, any more than a man flattened by a steamroller can be restored to life by being run over backwards.) What we are saying is that the long-term goal of economic policy should henceforth not be growth, but the structuring of collective existence so as to facilitate the good life. How this might be achieved is the subject of [our] final chapter. — How Much is Enough? Money and the good life

Edward and Robert Skidelsky’s book is important. The last two chapters in particular (“Elements of the Good Life” and “Exits from the Rat Race”) are essential reading for Escapologists.

In their penultimate chapter, the Skidelskys lay down some universal assets one should seek in seeking the good life (it is a far better refined and universal version of what we said here). Meanwhile, their suggestions in the final chapter are designed to nudge society in the direction of the good life and away from the obsessive pursuit of economic growth (which is the current state of things, public discussion of the good life having all but disappeared since the 1980s).

The basic belief that a somehow qualitatively ‘good’ life is more important than financial gain is and old thing, but this book puts it all down so succinctly and with reference to Western society’s current challenges, that it’s hard not to see this book as the most important one of the moment.

The book reanimates certain philosophical ideas (such as Aristotle’s Ethics and the Escapologist’s favourite, Epicurus) about good living, and questions the goals of Capitalism and the uses of wealth. It describes Capitalism as a kind of Faustian pact, one which we have the opportunity to renege upon or be duped by.

The main axis on which the book spins though, is a 1930 prediction by John Maynard Keynes (Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren) that we should now be well on our way to an ultra-short working week and maximum leisure time (2030 being a kind of singularity for Keynes). As we always say in New Escapologist, this utopia seems to be within our grasp but it inexplicably doesn’t seem to be happening. Why do we have to work such long hours just to get by when the technology and expertise and abundance of today is enough to cater for everyone? Why is soulless toil and a consumer-oriented idea of leisure now the standard mode of existence?

The Skidelskys shed light on this by examining Keynes’ prediction and current economic theory and data. The reason seems to be twofold: power (amoral distribution of wealth) and insatiability (ever-expanding definitions of what constitutes ‘enough’). Those are our enemies. Those are the things that must be curbed.

The cures offered by the Skidelskys’ last chapter are (a) a basic citizens income (a monthly or annual stipend to all citizens — a concept we discussed in New Escapologist Issue Four and may discuss again) and (b) a reduction in the pressure to consume (which we always talk about, perhaps most directly in Issues One, Three, Five and Six). It is good to have our ideas confirmed by people who know the full history and current mechanics of what we’re all talking about.

The book also features a history of utopian thinking; a spirited if somewhat sobering critique of both ‘happiness economics’ and environmental activism in relation to economics; and some explanations for how capitalism might not be a terrible thing inherently but has gone somewhat haywire in a Promethean kind of way. Read it. It’s important. Escapology for society.

Buy the complete back catalogue of New Escapologist with a 10% discount today.

Or buy the complete back catalogue on PDF, with £1 off the price each issue.