Prior to Getting Cancer, I Had Ambitions of Becoming a Managing Director.

These past nine years have been really good, probably better than if I hadn’t had cancer. Different things became a priority: spending time together rather than worrying about having a good job or thinking you need a big house.

Here’s a long article in the Guardian about how the terminally ill spend their time. They’ve reassessed, retooled, changed their priorities.

I’ve got limited time, so I’d rather be doing things with family and friends, and having a positive impact on the world around me. I’m not in the office wearing a shirt and tie any more.

and

I wish I had gone out more with my friends. I wish I had gone to parties and stayed out late. Living life free-spirited is something I feel I missed out on, and I regret that I didn’t take advantage of that when I was younger. Life is short and you should live it how you want, regardless of what people think. Don’t hold back. Say what you want to say and do what you want to do.

and

Prior to getting cancer, I had ambitions of becoming a managing director or CEO; I wanted to achieve something in my career. Within hours of the diagnosis, that disappeared. I don’t care for work any more

When those close to the end tell us these things, what they’re really saying is: “don’t leave it too late. Think about what’s important and do it. Live while you still can.”

That’s why they write it down or say it out loud. They’re not navel gazing. They’re blowing the whistle. They’re bringing us a message from the future.

But people so rarely listen. Even these people, the dying, didn’t listen.

The truth is, you’re mortal. You don’t need a cancer diagnosis to tell you you’re dying. The cancer patients in the article might even outlive you: you could get hit by a drunk driver on your way to return an ill-fitting shirt to Primark. A piece of masonry might fall on your head.

As one future corpse to another, I’m telling you now: don’t wait. Fuck this crap! Work less, take it easy, see some of the world, be with your loved ones, look at art, help others, eat well, get laid, get off your computer, be grateful, forget about Elon Musk, ignore the crap that doesn’t matter. Take your socks off and feel the grass beneath your feet. Look at the moon and stars and think wow, we’re really on a planet. Marvel at your breath in the cold night air. Remember the faces of your grandparents.

*

Gone Fishin’

I’m reading some Philip Roth. In The Anatomy Lesson, a character says:

Maybe you are tired. Maybe you want to hang a sign on your door, Gone Fishin,’ and take off to Tahiti for a year.

I’d completely forgotten about Gone Fishin’. It’s one of of those great Boomer phrases, up there with Keep on Truckin’ and Eat at Joe’s.

In all my time thinking about escape and mini-retirements and going valiantly AWOL, I don’t think I ever remembered Gone Fishin’.

Anyway, put that sign on your door. Go to Tahiti for a year. Good advice for anyone.

*

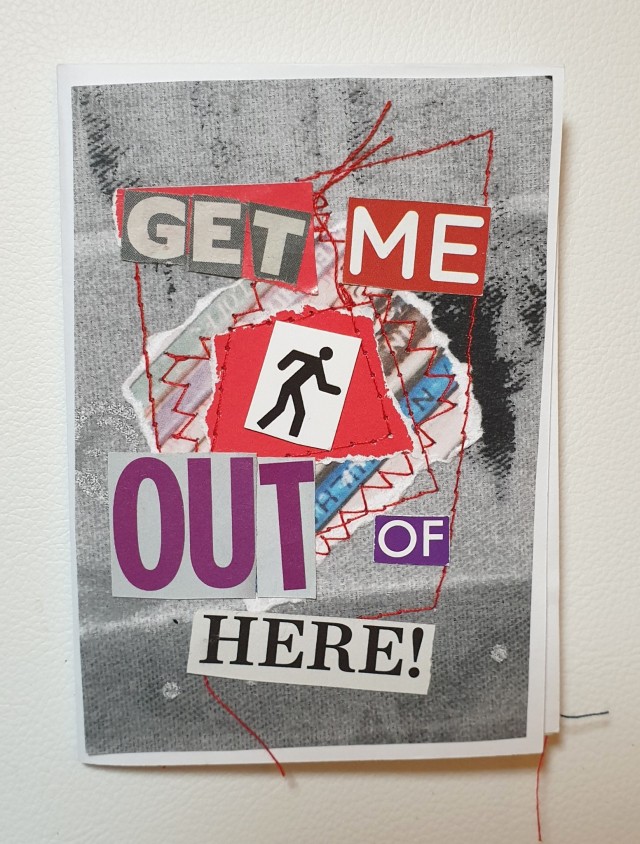

Escape Substack?

Substack, the platform I use for the New Escapologist newsletter, is crawling with Nazis. Urgh! Readers have emailed to say they’ve unsubscribed from the newsletter for this reason. Thanks a lot, Nazis.

So should I stay or should I go? Obviously I should go. Leaving is something I’m great at! But I can’t leave without first finding an alternative, because doing so would all but end New Escapologist. An escape plan is in order.

Here’s Friend Carrie on the nature of this particular trap:

The problem for many people who publish on Substack is a problem we’ve previously seen on other platforms, including Twitter. It’s enabled people to establish an audience and in some cases a career, and that means leaving could cause financial harm to people who abandon the platform. Even if other platforms were morally pure, and very few of them are, the people demanding moral purity from their newsletter creators are rarely the people who will be financially harmed by it.

In addition, many of the people being urged to quit are marginalised people – the very people who can least afford the financial hit.

As it happens, I don’t make money from Substack. Not directly. My newsletter is free, so I’m not in particularly deep. My using the platform does not fund Nazis or (so far as I can tell) help them in any way.

But the newsletter allows me to sell the magazine (and my books via my personal list), so my bind is very similar to someone who does profit directly from Substack.

I’m sharing a platform with Nazis. Which is horrible. And embarrassing. But we all share platforms with Nazis all the time: on almost any social media platform and even the lovely Old Web is full of Nazis because there’s no moderation out there at all (though really every website is a different independent platform, so there’s always a nice little moat to separate us from the jackboot-wearing Eugenicists).

So I think “why should I go?” Obviously, I shouldn’t have to go, but equally obviously I do have to go. Yet I’m not sure there is anywhere to go. It’s a classic escape problem.

Carrie quotes another blogger (from Substack!) who airs this very frustration:

It is exhausting just trying to exist with any level of moral consistency online nowadays. And the people who keep being handed the keys to several kingdoms don’t ever bother to worry about it. They just let us tear ourselves apart trying to do the right thing while they feast. It’s all a game to them. It’s not remotely a game to us. So there’s no equivalence.

It is exhausting.

As a trans woman, Carrie is generous to give a pass to people who might not have the financial liberty to leave Naziville. I pretty much do have the financial liberty but only if I can find an adequate alternative way to send my newsletter.

So where shall I go, folks? While Substack is free, Ghost and Buttondown are expensive. Ghost in particular would cost me $199 per month, charged yearly, which is completely prohibitive. Other platforms I’ve seen are too rubbish or unreliable (or are crypto- or AI-oriented, meaning the Nazis are probably already there).

I could go back to Mailchimp, which I used for New Escapologist before Substack, but it really sucks. Its creative interface is awful and half the emails don’t make it through spam filters. One of the nice things about moving to Substack last year was reconnecting with people who thought I’d died. “You’re back!” they all said.

I don’t particularly want to stay on Substack. I have as much to lose from the rise of Fascism as anyone.

So it’s frustrating. I’d leave. I will leave, by jove! But I have no idea where to go. Answers in the comments please. Help Mr. Escape escape.

*

Prince Charles

Charles Bukowski:

How in the hell could [anyone] enjoy being awakened at 8:30 a.m. by an alarm clock, leap out of bed, dress, force-feed, shit, piss, brush teeth and hair, and fight traffic to get to a place where essentially you made lots of money for somebody else and were asked to be grateful for the opportunity to do so?

8:30?! It shows how little the onetime factotum knew about conventional day jobs. Isn’t it more like 6:30?

*

Get up at 10:30 instead. And read New Escapologist.

Xodus: Escaping Twitter At Last

I’m here to tell that you don’t need to be on Twitter anymore. The network effect is broken and you can finally escape its clutches. (And you should!)

If you’re a browser of Twitter, you probably see a lot of crap. It’s no longer your friends or even organisations you’re actually following anymore.

If you’re a creator who once used social networks to grow your audience, those followers aren’t seeing your tweets anymore. Here’s Cory Doctorow on the facts:

Six months ago, [Radio station and publisher] NPR lost all patience with Musk’s shenanigans, and quit the service. Half a year later, they’ve revealed how low the switching cost for a major news outlet that leaves Twitter really are: NPR’s traffic, post-Twitter, has declined by less than a single percentage point.

NPR’s Twitter accounts had 8.7 million followers, but even six months ago, Musk’s enshittification speedrun had drawn down NPR’s ability to reach those users to a negligible level. The 8.7 million number was an illusion […] On Twitter, the true number of followers you have is effectively zero […] because every post in their feeds that they want to see is a post that no one can be charged to show them.

Whenever I visit Twitter these days, I’m usually greeted by a single notification. The days of 20 or 40 ringing bells are long behind me. Worse, the notification is never a message or an RT or anything remotely useful. It’s inevitably a follow from a sex bot, i.e. some sort of phishing scam.

This daily non-experience, combined with how nobody sees my tweets anymore (either because they’ve sensibly left the platform or because I’m hidden by the algorithm) makes me realise… I’m free. Finally free! I can leave!

And so can you. Here are the instructions on how you too can leave Twitter.

It’s a shame really. Twitter was useful for contacting people and finding things out in realtime, but it just doesn’t work that way anymore. It’s a busted flush. I’ll probably lose touch with some people whose main point of contact is Twitter; I’ve contacted the ones I can think of to give them my email address.

The nightmare is over. No more Twitter.

In my case, it leaves me social media free for the first time in over 20 years! It was 2003 when I joined a platform called Friendster. I might eventually come over to Bluesky for fun, but for now I think I’ll enjoy the fresh air and resounding lack of network effect in my life. I advise you all to do the same. Deactivate your accounts and be free.

To celebrate what I’m calling the Xodus, I recommend reading this potted history of social media in The Atlantic magazine. It charts the incremental changes that took Twitter and Facebook from a useful database of social connections to nightmare of conspiracy theories and nonsense content that is ruining the world.

Now all I have to deal with is the problem of Substack…

*

Weeping in the Parking Lot

It was still dark. I left home in blackness and I returned in blackness.

Maybe a tad bleak for New Escapologist but it’s on theme.

Life on a Tiny Houseboat

Thanks to Reader S for drawing our attention to this pleasant video.

Reader S writes:

I’d experiment with this at least, if I had an extra pair of hands to help me. Plus accessibility to a canal network such as this, of course. Don’t know a thing about boats, though.

Indeed! Those are the obstacles. As we know, there are advantages and challenges of boat life.

It’s nice to see the phrase “continuous cruiser” come up again. And I also like how this man seems to have all the accents, perhaps as a result of moving around so much.

*

Our latest issue is Issue 15, available now in print and digital formats.

Letters to the Editor: Why No Photographs?

To send a letter to the editor, simply write in. You’ll get a reply and we’ll anonymise any blogged version.

Reader X writes:

Hey Robert,

Finished slowly reading Issue 15 because I wanted to suck the marrow out of the bones of Experiments in Living. Delightful!

But… why no photographs? I was so hoping to see what Henry’s humble home looked like, although admittedly you did a most excellent job in describing it. Is adding photos just prohibitively expensive or just not the aesthetic you want to pursue?

Just starting a reread. Always entertaining to hear your voice on the page. Don’t want to unduly add to your anxiety but already looking forward to the next issue…

*

Hello X,

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed it. I had a reflective read of both issues last night and I must admit to being very pleased with it all. I’m also happy that people are buying it: it feels like a magazine written just for me, so it’s validating that others are interested (even enthusiastic!) too. I feel a strong sense of connection with you and the other readers. It’s wonderful. I’m very grateful for it.

It’s funny you should mention photographs as I’ve been thinking of using photography in the magazine for the first time. Up to now, I’ve never used it in New Escapologist. As you rightly suspect, it’s not the aesthetic I want. However! This aesthetic (non-digital, perhaps a little bit Victorian) was informed by pragmatism some 16 years ago: photographs didn’t reproduce particularly well with the printing technology I used. We’ve moved on since then and we could theoretically print photographs if we wanted to.

Not photographing Henry’s place was a deliberate decision though. It would have compromised his privacy. I’m slightly amazed that he allows me to publish details about his life at all. I didn’t want to use technology (my iPhone camera) in his presence, nor would I want those pictures to find their way onto the Internet, on which he has robustly turned his back. So even if photography was technically and aesthetically possible, I would never have published photographs of Henry’s house.

Two possibilities exist for breaking my no photography rule: one is my friend Alan who takes remarkable documentary photographs (usually on film) and with whom I already collaborate a little. Another is a photo album I inherited from my friend Kat: it depicts the louche alternative life of a theatrical couple in the 1950s. I want to research the photos a little and maybe write about them. If I do this for New Escapologist (as an example of successful outsider life), it would be a shame not to reproduce some of the photos. So maybe you’ll get photographs soon! I’m mulling it all over.

Oh! You might also have noticed that the inside covers of the print edition can use colour ink now. This is available to us at no additional cost so I like the idea of using that. In Issue 15 (exclusive to the print version), the inside back cover shows the attractive modernist artwork from the cover of Escape, Escapism and Escapology, one of the books we reviewed. I decided not to label as such (though credit to the artist and the owner of the painting can be found in the masthead) to allow it to pique people’s curiosity.

Rob

*

If other readers have thoughts concerning our aesthetic and the use of photographs, please comment on this post or send me an email. Print editions of Issue 14 and 15 remain available to purchase.

A Burning Desire for the Open Air

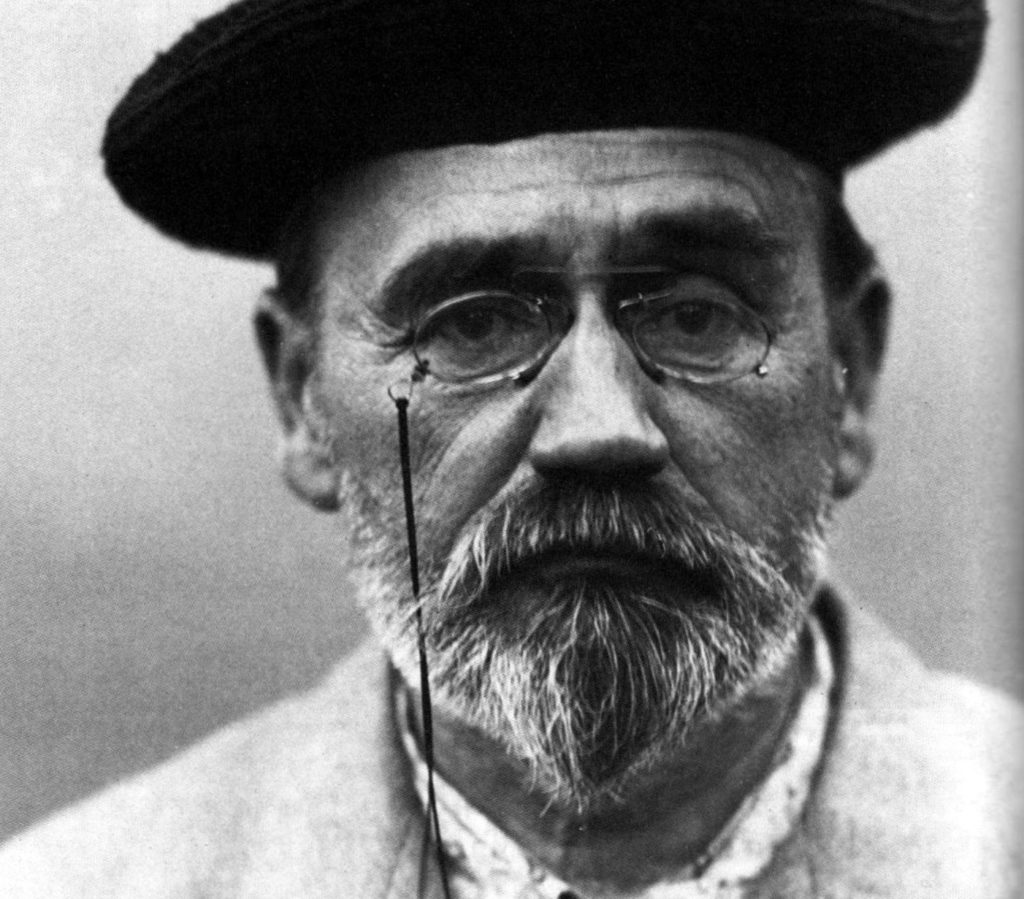

Émile Zola didn’t take any prisoners when describing the lower middle classes in 1868. I’m reading his novel Thérèse Raquin:

Thérèse, who finds herself living in stultifying domestic mediocrity, longs for freedom:

They brought me up, they received me, and shielded me from misery. But I should have preferred abandonment to their hospitality. I had a burning desire for the open air. When quite young, my dream was to rove barefooted along the dusty roads, holding out my hand for charity, living like a gipsy.

and

You will hardly credit how bad they have made me. They have turned me into a liar and a hypocrite. They have stifled me with their middle-class gentleness, and I can hardly understand how it is that there is still blood in my veins. I have lowered my eyes, and given myself a mournful, idiotic face like theirs. I have led their deathlike life. When you saw me I looked like a blockhead, did I not? I was grave, overwhelmed, brutalised. I no longer had any hope. I thought of flinging myself into the Seine.

This reminds me of a film I saw recently called His House. It’s a horror film about Sudanese refugees who must start a new life in the English Midlands. Of the low-level English pen-pushing bullies they encounter, they say:

They don’t want to be reminded that it is them that are weak. How poor and lazy and bored they are.

It’s not only homelife Zola despises. He really takes aim at the office. People who want to work in offices, represented by Thérèse’s meek husband Camille, are idiots and try-hards. Her secret lover Laurent meanwhile, a more creative fellow albeit not a successful one, must also work in an office but against his will:

With stomach full, and face refreshed, he recovered his thick-headed tranquillity. He reached his office and passed the whole day yawning and awaiting the time to leave. He was a mere clerk like the others, stupid and weary, without an idea in his head, save that of sending in his resignation and taking a studio. He dreamed vaguely of a new existence of idleness, and this sufficed to occupy him until evening.

In Zola’s world, some people (like Camille) are idiotically seduced into The Trap by empty promises of status. Others are pushed into it by circumstance: through financial desperation or through their failure to do something better. Loverboy Laurent isn’t a very good portrait painter but, when left to his own devices later in the book, he starts to thrive. Time and space are what he needs but the system denies them to him.

Laurent’s failure to live up to his real calling and Thérèse’s deep domestic boredom lead them on a chaotic path of adultery and murder. They become a social problem. The system fails individuals, obviously, but in doing so, fails us all.

*