Reprioritisation

Further to yesterday’s post about the Guardian report on younger people who ditched hard work:

James, a 31-year-old in Glasgow, had always worked hard, from striving for a first at university to working until 8pm or 9pm at the office in the civil service in the hopes of getting noticed. But during lockdown in 2020, James had an epiphany about what he valued in life when reading the book Bullshit Jobs by the anthropologist David Graeber. “He talks a lot about how jobs that provide social utility are generally pay-poor while the inverse are paid more,” James says.

Hooray! Graeber’s legacy lives on. His message was heard. Meanwhile, New Escapologist (and the Idler and others) will continue to chip away at grind culture and the Protestant Work Ethic from the sidelines.

[James] now focuses on his life, putting his phone on aeroplane mode while doing activities such as hiking, reading and watching films. “I still value work, I’m very committed to my position. But I’ve just realised that this myth a lot of millennials were told – graft, graft, graft and you’ll always get what you want – isn’t necessarily true,” James says. “It’s a reprioritisation.”

*

New Escapologist Issue 14 is available now from our online shop.

Good News If True

The Guardian reports that young people are ditching “overtime and excess work stress” in favour of “family and fun.” Good news if true.

When Molly, 35, was growing up, she remembers the message of “work hard and you’ll get rewarded” being drilled into her by parents and schoolteachers. As a result, she spent her early career putting in the hours. But when she had a child and sought a flexible work pattern at her professional services job, the company denied her request. “I was replaceable,” she says. “I was very much a cog in the machine.”

I always enjoy hearing about the epiphany. I collect epiphanies: the memorable moment, perhaps with one foot in the commuter carriage and the other still on the platform, when a person snaps and says “no more” and “there are other worlds than these.”

This said, I’m always amazed that it takes such an existential shock as having a child or getting ill to discover that “work hard and you’ll get rewarded” is bollocks.

The most “rewarded” in our society have not worked hard for it: they’ve usually inherited their wealth in some way or were born into the sort of privilege that results in playing the game on easy mode, or else they’ve done something clever and/or immoral. There are exceptions, of course, and the media is all too happy to spotlight them to prop up the myth of meritocracy.

Meanwhile, people who work hard are usually hospital porters or cleaners or the hardhats who maintain railway lines at night. They bust a gut and aren’t rewarded for it beyond the essential basics that will keep them coming back to work. Some of them die at work.

These twin observations–that the rewarded do not work hard and the hard-working are not rewarded–are as plain as day. You shouldn’t need a baby or a tumour to come along to shock you into sense. Then again, we get the “work hard and you’ll get rewarded” message on all sides, don’t we? From parents and teachers and colleagues and bosses and the television. It’s insidious and it’s everywhere. It’s called the Protestant Work Ethic and it’s a scam.

Molly is one of many in her generation readjusting their work-life balance to focus less on their job. Research published this month from King’s College London based on surveys from 24 countries found that just 14% of UK millennials (people born from the early 80s to mid 90s) believe work should always come first, compared with 41% in 2009.

So maybe it is true. Good news indeed.

*

New Escapologist Issue 14 is available now from our online shop.

Perruque

Here’s a fun word I haven’t come across before: perruque. It means to pilfer time or surplus resources from work.

It’s not in either of Glenn’s Glossaries, which is probably forgivable since I found it in an essay called “18 Semiconnected Thoughts on Michel de Certeau, On Kawara, Fly Fishing, and Various Other Things,” which some might say is off the beaten track.

It comes up when the essayist, Tom McCarthy, is talking about Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life, a 1974 book about the ways in which people personalise or adapt what the built environment gives them. (To give you a better idea of what this means, the cover usually shows an image of desire lines).

McCarthy writes:

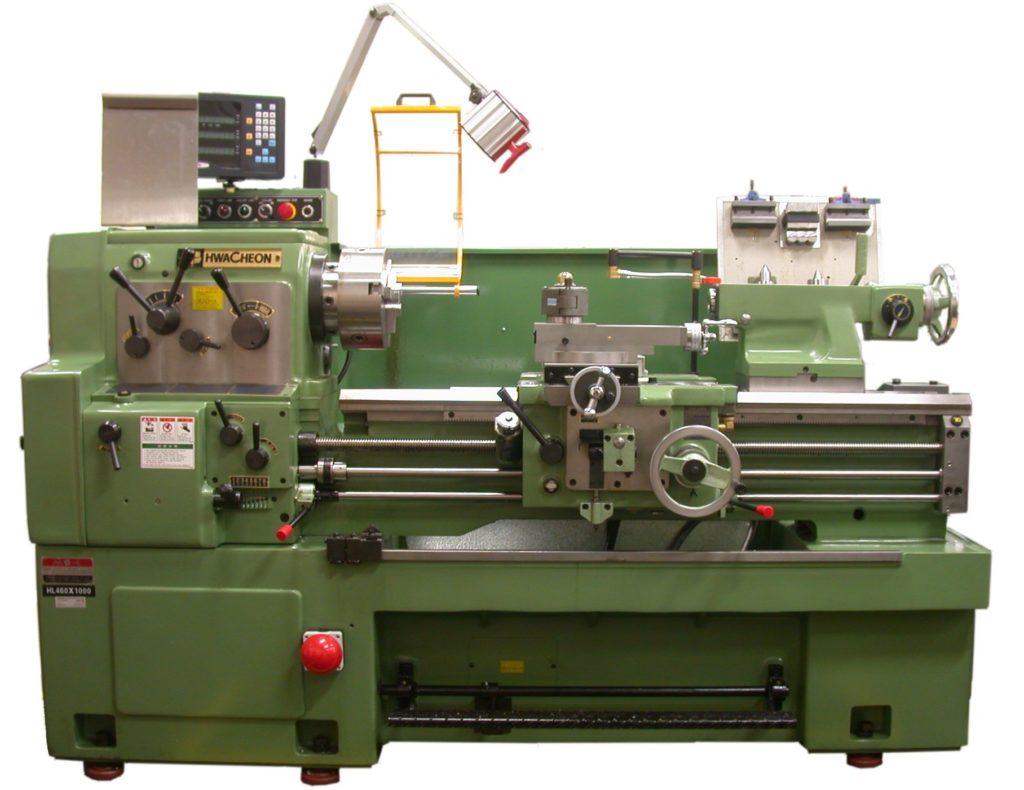

Perruque is when the little guy, the worker, does something for his own ends under the guise of obediently serving his employer. When a cabinet maker uses a lathe to make a piece of furniture for his living room, that’s perruque; so is when a market researcher or ad agency employee abandons himself to reverie for half an hour. Whacking off on the boss’s time.

I mention this excitedly to my wife who says perruque is the French for “wig.” What would that have to do with this? I ask, meaning etymologically. “Subterfuge,” she says.

(We laugh because of a moment we remember in Samuel Pepys’ Diary in which Pepys, noticing a fashion for powdered wigs, has a wig made of his own hair and passes it off as real for his own amusement; as well as being delightfully puerile and containing the idea of Pepys being blissfully unaware of everyone around him saying “hark at Sam wearing a wig of his own hair,” he has spectacularly missed the point that wig-wearing was supposed to be conspicuous).

Samara, ever brilliant, owns a copy of The Practice of Everyday Life so we pluck it from the shelf and find she earmarked the page about perruque years ago.

The example of the cabinet maker is right here in de Certeau (a bit lazy, McCarthy). He also provides the lovelier example of “a secretary’s writing a love letter on company time.”

He continues:

Accused of stealing or turning material to his own ends and using the machines for his own profit, the worker who indulges in la perruque actually diverts time (not goods, since he uses only scraps) from the factory for work that is free, creative, and precisely not directed toward profit. In the very place where the machine he must serve reigns supreme, he cunningly takes pleasure in finding a way to create gratuitous pro-ducts whose sole purpose is to signify his own capabilities through his work and to confirm his solidarity with other workers or his family through spending his time in this way. With the complicity of other workers (who thus defeat the competition the factory tries to instil among them), he succeeds in “putting one over” on the established order on its home ground.

A very fine example of sticking it to The Man. It’s also an example of what I once described as “escaping the Holodeck using holographic tools.” You mustn’t feel bad about perruch. You owe your escape to the greater good and it’s no fault of yours if the captor has left some handy holographic shovels and power drills lying around.

New Escapologist was originally a perruch project of sorts: blog entries pecked out on company time and a pilot issue printed on A4 stolen from temp jobs (as apparently was Processed World, another magazine about office confinement).

*

Issue 14 of New Escapologist is available from our online shop.

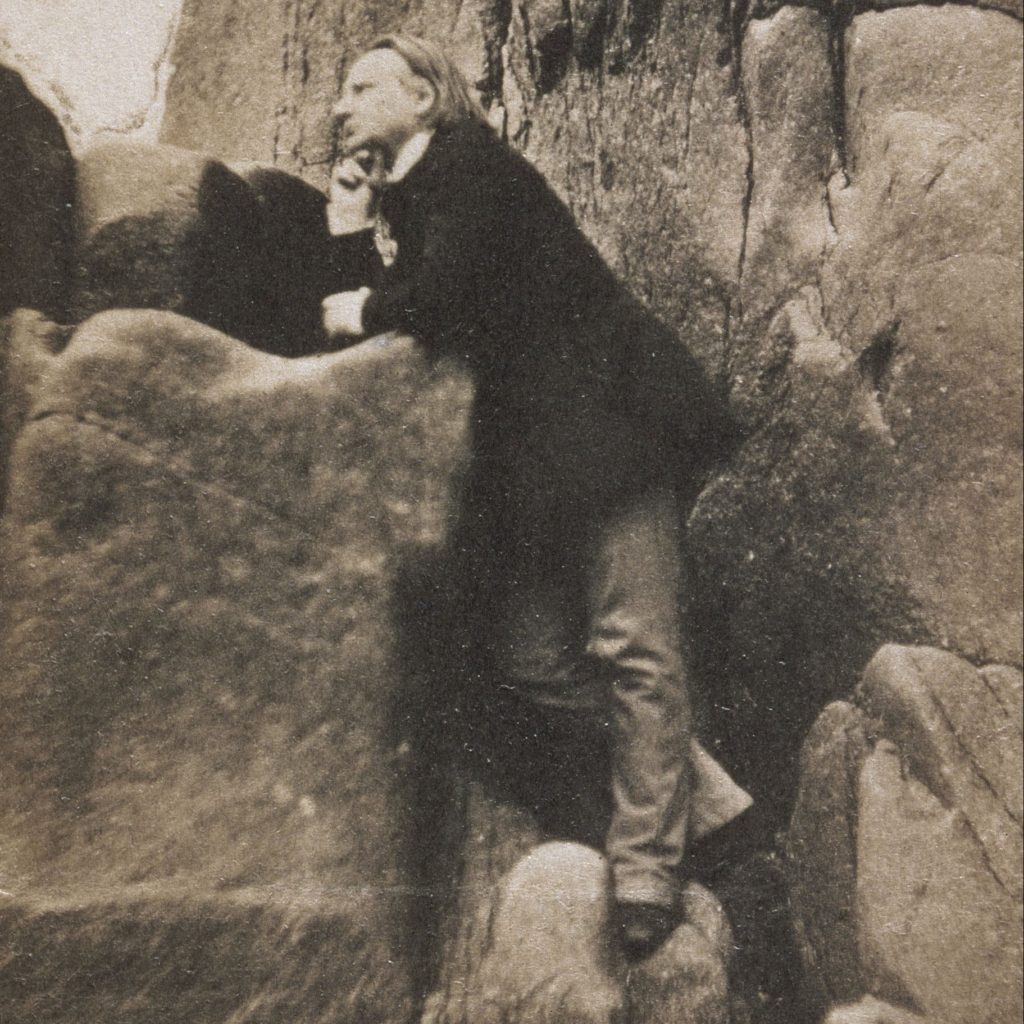

Hugo

My tastes are aristocratic, my actions democratic.

Thus spake Victor Hugo, writer of Les Misérables and The Hunchback of Notre Dame and many, many other beautiful novels.

He reminds us that we can enjoy rarefied art and culture without being assholes about it.

Dreamer Hugo:

Novel(s)

It’s about time I told you — the readers of New Escapologist — about my novel(s).

My first novel was released this year. It’s called Rub-A-Dub-Dub. I’ve been promoting it here and there but I’m not sure I’ve mentioned it properly to you yet.

It wasn’t supposed to be “an Escapological novel” but it sort-of is. It’s certainly about the indignities of wage labour.

I was keen to avoid this being about office life, so our hero’s job ended up being on trains. He cleans seat-back trays and collects rubbish and unblocks toilets on long-distance trains from Edinburgh to London. He doesn’t live in either of those cities though, so his commute to work also involves trains and, as such, he spends a sizable part of his life on them. He’s not even sure sometimes if he’s working or commuting (a feeling familiar to many since even the longest commute is not typically remunerated: vast swathes of human life being spent in lurching transit is just a cost of doing business).

A colleague eventually tells our man that his problems might stem from his odour problem! He’s smelly, in large part because of his exertions. And so he embarks on a voyage of self-improvement (“Getting Better” he calls it), which starts with luxurious soaks in the tub. It’s not just about being smelly or unsmelly: it’s about taking care of yourself more generally, slowing down, taking the time to think.

Our man’s problem isn’t really his smelliness at all in fact. He’s the victim of a hundred years of decision-making for which he wasn’t present. Choices made in the Industrial Revolution dictate how he must spend his days now. He doesn’t want to believe in Fatalism but the more he mulls over his problems, the better he comes to understand that his place in history is as much to blame for his predicament as anything he’s done wrong himself.

This is the Escapological crux of it all. I didn’t know I was writing Escapology but I was. Or at least I was writing about the problem for which Escapology is a personal solution.

It seems that the indignity and unfairness of work is one of my obsessions and I wonder now if it will make an appearance in any future novels I write too.

*

Rub-A-Dub-Dub is available in paperback and digital formats from P&H Books.

Letter to the Editor: Backwards, Away From the Sunlight

To send a letter to the editor, simply write in. You’ll get a reply and we’ll anonymise any blogged version.

Reader L writes:

I just read the magCulture interview. Why do you put so many of your books in your bookshelves spine-in? Are those the ones you’ve read and the spine-out group is fresh reading fodder?

*

Hi L. Yes, that’s correct. But it’s only temporary. I saw a YouTuber doing it and I thought it would be cool to get the live visualisation of read versus unread. I’ll put it back to normal soon though because it’s hardly practical for finding a specific book.

The same YouTuber described it as “playing with my library.” I thought, “hmm, I never play with my library. Maybe I’ll play with my library.”

It’s also fun to see the different colours of book paper: some of them aged and others new, some of them bright white and others burnt umber or practically orange.

The room is very sunny so I’m always aware that the spines of my books are becoming gradually bleached. Some yellow spines like that of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, which I’ve owned for 20 years, is as good as white now. This gradual bleaching is always on my mind like how Foster, a librarian in Richard Brautigan’s The Abortion is troubled by his surplus collection being housed in a drippy cave. So it’s nice to have a break from that worry while they’re all turned backwards, away from the sunlight.

I realise this has very little do with Escapology. Unless of course… it does?

Feeling bookish now? How about buying one?

Woes Wanted

We have a column in New Escapologist called Workplace Woes. It’s an opportunity for readers to anonymously blow off steam about their jobs, past or present.

In Issue 14 there was the story of an office Halloween Party that went from embarrassing to worse. There was also the tale of workplace racism out of the clear blue sky. Oh! And the story of animals escaping from a pet shop.

If you’d like to vent your spleen, please send me your Workplace Woes by email. All stories will be treated with utmost confidence. That’s the whole point.

Please keep them under 200 words (no need for elaborate scene setting: just cut right to the chase). Stories can be funny or anger-inducing or a little of both. It’s all good.

It would be particularly nice to hear some woes from the worlds of retail or hospitality and also some outdoorsy woes (e.g. construction industry), but if your story is simply office-based then that’s good too!

The deadline for Issue 15 is September 20th but any latecomers can be saved for future editions.

Thanks everyone. Over to you.

Visualise an Alternative, Save Your Money, Do a Runner.

I’ve arranged my life around the principle of living and working in the same couple of rooms. You might have heard of the fifteen-minute city? Well, I live in the one-minute city.

We’re proud to announce that New Escapologist is now stocked by magCulture, London’s premier destination for printy-printy mag-mags.

It’s a real candy shop of top-drawer paper productions so it’s flattering that they’ve agreed to put us on their shelves.

To draw their customers’ attention to our magazine over the long-established others, I did a little interview with proprietor Jeremy. It’s worth a read: Jeremy asks the right questions.

If you don’t like your boring job or the people around you or the town you live in, you can knuckle down and enact a plan of escape. Visualise an alternative, save up your money, do a runner. It’s different to escapism, which is about temporarily fleeing the mundane by watching films or reading novels or whatever.

We’re interested in people who have turned their life upside-down by escaping the inadequacy they’ve drifted into through the bullying of capitalism or the demands of society, and into a more creative life of their own design. You know, Escapology!

You can also subscribe to the magazine at our very own online shop.

Outsiders

The “final” issue of New Escapologist in 2017, before our triumphant return earlier this month, was subtitled “Outliers.”

The idea was to celebrate outsiders. By definition, outsiders are successful Escapologists. They’re on the outside. They’ve escaped.

Reader Tom draws my attention to Rolf Dobelli’s book The Art of the Good Life in which Dobelli writes:

Outsiders enjoy a tactical advantage. They don’t have to adhere to establishment protocols which could slow them down. They don’t have to dumb down their ideas with visually snazzy [and] ridiculous PowerPoint slides.

They can happily ignore convention and are under no pressure to accept invitations or take part in events simply to “show face”. […]

What’s more, their position off the intellectual track sharpens their perception of the contradictions and shortcomings of the prevailing system, to which members of the club are blind.

I think that’s correct, which is why in Issue 14, I interviewed the Iceman.

The Iceman is probably the ultimate outsider and I love him so much that I wrote a whole book about him last year. Thankfully this wise prodigy had a little more to say and I was glad to speak to him again.

Reader Tom writes: “Look to the outsiders. The groups of people on the fringes or dabbling in areas which aren’t mainstream. They have aces up their sleeve which they might be willing to share.”

I’d go one better. Learn from outsiders. But also, be an outsider.

Witnessing the lives of outsiders is what turned me into an Escapologist in the first place. I had a day job in an office while spending my evenings doing stand-up comedy and reading about performance history (including the history of magic, which switched me onto Houdini). On the evenings I’d meet people who truly didn’t give a shit: they didn’t care about making enough money, they had no lofty goals, they just entertained and intrigued and worked on their act. Unlike the people in the office and unlike half of myself, they had integrity.

*

Inner Weirdo

I’d been looking forward to reading a book called Solitude: In Pursuit of a Singular Life in a Crowded World. Life is too crowded, too busy, too loud. And I wondered if the book might contain some solutions for Escapologists.

In the end, I didn’t enjoy the book at all. It barely feels like a real book; almost like one of those prop books you might see in Ikea to make a bookcase look nice on the display.

The biggest problem is the author’s fixation on technology. He deploys it usefully enough in the first couple of chapters to illustrate the problem of the crowded world through tech-enabled connectedness, which is fine as it goes, though even at that early stage I was thinking “but that’s only one of the problems, what else have you got?”

He returns to it time and time again, boringly explaining the basics of Twitter Analytics, emoji, and Rotten Tomatoes as if we’d never heard of them. I assumed the book must be old, perhaps from 2006, but the copyright page shows a publication date of 2017. It’s very odd.

I cheered up a bit when Quentin Crisp made an appearance in Chapter 5. The author seems to find Crisp’s wit and defiance personally important and some of his passion is on the page. But then we’re back to moaning about the Internet after four short pages of circling some rather basic ideas about conformity and individualism.

Anyway, there is the occasional nugget of something. For example, I like this moment, which is buried in the middle of the book at the end of a boring digression about whether “smart” thermostats can have beliefs and tastes (they can’t: it’s just anthropomorphism, though the author never says this):

today we need to safeguard our inner weirdo, seal it off and protect it from being buffeted. Learn an old torch song that nobody knows; read a musty, out-of-print detective novel; photograph a honey-perfect sunset and show it to no one. We may need to build new and stronger weirdo cocoons, in which to entertain our private selves. Beyond the sharing, the commenting, the constant thumbs-upping, beyond all that distracting gilt, there are stranger things waiting to be loved.

(I didn’t know what an “old torch song” was; I thought maybe the author was into a defunct indie rock band called Torch whose name should be styled with a lower-case “t”, but apparently it’s a genre of love song. Cool.)

I agree with what he’s saying here but only up to a point. Escapologists should avoid the strong force of common opinion by way of protecting our minds and nurturing our own insights. Reading books or watching films properly or restfully playing the violin instead of gawping at the television, for example, is indeed something we’ve talked about before.

It’s better for you (because who wants to be a zombie, merely reacting to whatever comes along?) and better for the world (because society needs individual thinkers and contrariains and, if nothing else, a control group). But we don’t need to “safeguard our inner weirdo” for its own sake exactly. Instead, courting internal uniqueness happens naturally, emerging almost as a by-product of our bigger projects.

When you’re working on an escape plan to say goodbye to the office or if you’re trying to build the creative muscles to write your first novel, the inner weirdo will thrive of its own volition.

Don’t worry about the claptrap of the digital or workaday worlds. Just ignore them and do your own beautiful thing.

*