The Mainstream Promise is Simply a Lie

From Confronting Capitalism by Vivek Chibber:

the mainstream promise–that if you work hard and play by the rules you will make it to the top–is simply a lie. The rules are what create the misery.

The basic set-up of capitalism is simple–you show up for work every day, work hard, and do what you’re told. The promise is that if you abide by these rules you will be rewarded with the good life. The promise is based on a very simple premise–that there is a link between effort and reward. If you work hard, the work will pay off.

But the secret to capitalism is that there is no reliable connection between effort and reward. […] This is a basic fact about capitalism, and it is built into the system. It is the natural condition of an economic system in which the bulk of the population is given a simple choice: “Work for what we offer or go without a job.”

What determines people’s economic fate in capitalism is not their effort but their power. And employers always have more power than workers.

There’s so much more in this handy little book that should be of interest to Escapologists (or indeed anyone who senses injustice in their work life but is yet to articulate it).

I’ll be quoting a little further from Chibber in the forthcoming Issue 14, which you can get via Kickstarter here.

The Thrilling Adventures of Escape Guy

You all know Escape Guy, don’t you?

He’s in the header of this very website and we used the same image on the cover of the magazine for a while.

He’s an ISO Standard symbol for an emergency exit. I was doing some research into this today and it turns out there’s variations on the theme. Loads of them.

For instance, here’s Escape Guy clambering out of a window:

Escape Guy always helps others to freedom:

He’s equipped for any occasion. Even leaving Planet Earth:

But mind that hole!

Catch him if you can:

But disembark carefully:

Escape Guy frees his mind by picking some mushrooms:

“Can’t. Reach. Drainage. Button.”

Almost home, Escape Guy!

Escape Guy takes a shower after a long day of fleeing:

Goodnight, Escape Guy.

THE END

PS: Be like Escape Guy and buy my book.

In Spite of His Indolent Ways

I’ve just read Little Women. There was a copy on a special display in the library and curiosity got the better of me.

Much of it is too winsome (is “twee” the right word?) for my tastes and the only March Sister I could remotely fall for was Jo. I like her mildly rebellious ways and she’s the only sister who seems to have a brain in her nut.

The “realer” chapters toward the end, which seem to be the ones best remembered, are very good though and I suppose you need the naff stuff if you’re to feel anything later on.

Anyway, there’s a line I wanted to share here for its Escapological energy:

in spite of his indolent ways, he had a young man’s hatred of subjection,–a young man’s restless longing to try the world for himself.

Isn’t that nice? It’s about Laurie, the March sisters’ only friend who is neither elderly nor an employee of theirs.

I must say I never got over the “hatred of subjection” or the “longing” described here so it’s not only native to young men. I’m 40 now (my first escape was at 26) and I still like to try the world for myself (despite my Laurie-like indolence). Keep the fire alive — quietly!

Luckily, there is advice from Jo March about what to do if you, like me, share this young man’s passion:

“I advise you to sail away in one of your ships, and never come home again till you have tried your own way,” said Jo, whose imagination was fired by the thought of such a daring exploit.

Will do.

For more inspiration on how to try the world for yourself, subscribe to our magazine here.

Kicky-Kicky, Start-Start

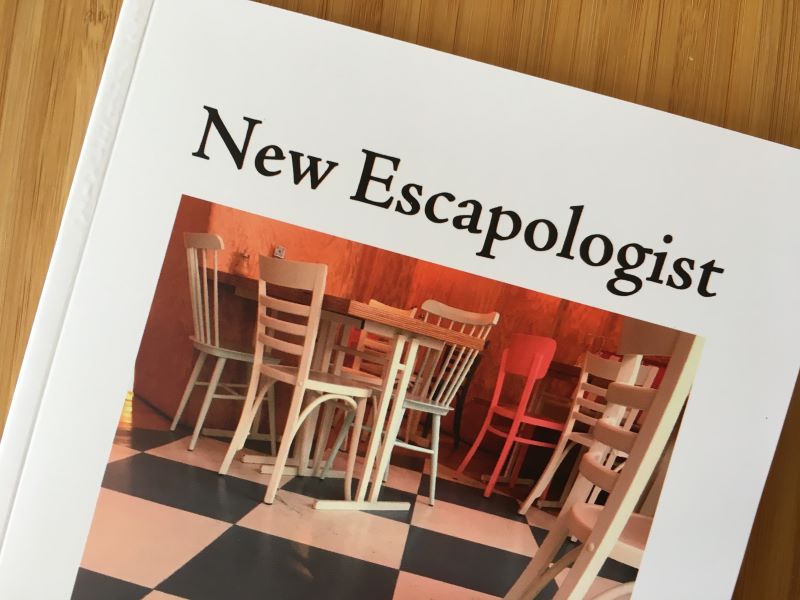

New Escapologist is a small-press magazine about escape.

We do not dwell on short-term or commercial escapes like television or beach holidays: we’re far more interested in well-planned, longer-term escapes from the worker-consumer treadmill into lives of imaginative creativity.

Yes indeed, there’s a Kickstarter campaign running RIGHT NOW to bring back New Escapologist as a small press magazine.

Thanks to a speedy response from the readers of our newsletter, the campaign is going extremely well but every single backer counts. Even if we make the target, we still want as many readers as possible. We’re trying to build a culture more than a “product”.

Kickstarter is currently the only way to buy the new issue or to subscribe (print and digital versions both available), so please visit the Kickstarter page to read more and to consider helping us along with a pledge. Why not get in on the ground floor of this amazing new cultural force to be reckoned with?

Thank you to everyone who has backed the project so far and to everyone else currently thinking about it. Let’s go!

Tinkers Bubble

Founded in 1994, Tinkers Bubble is England’s leading off-grid woodland community: an experiment in rural living that provides low-impact dwellings and a land-based livelihood to a changing roster of 16 residents.

From The Guardian:

It is owned by a community benefit society, and the current residents, most of whom arrive as summer volunteers, are sustained by the income from a steam-powered sawmill, apple orchard and press (which produces a lively dry cider) and cottage food production, including heritage salad leaves. The community’s 20 dwellings and outbuildings are dotted around a thatched communal roundhouse, all sitting amid the lofty firs.

And there’s a short documentary about it on YouTube:

*

New Escapologist is returning to print. To bridge the gap, why not get a copy of I’m Out or The Good Life for Wage Slaves?

Twin Book Recomendations

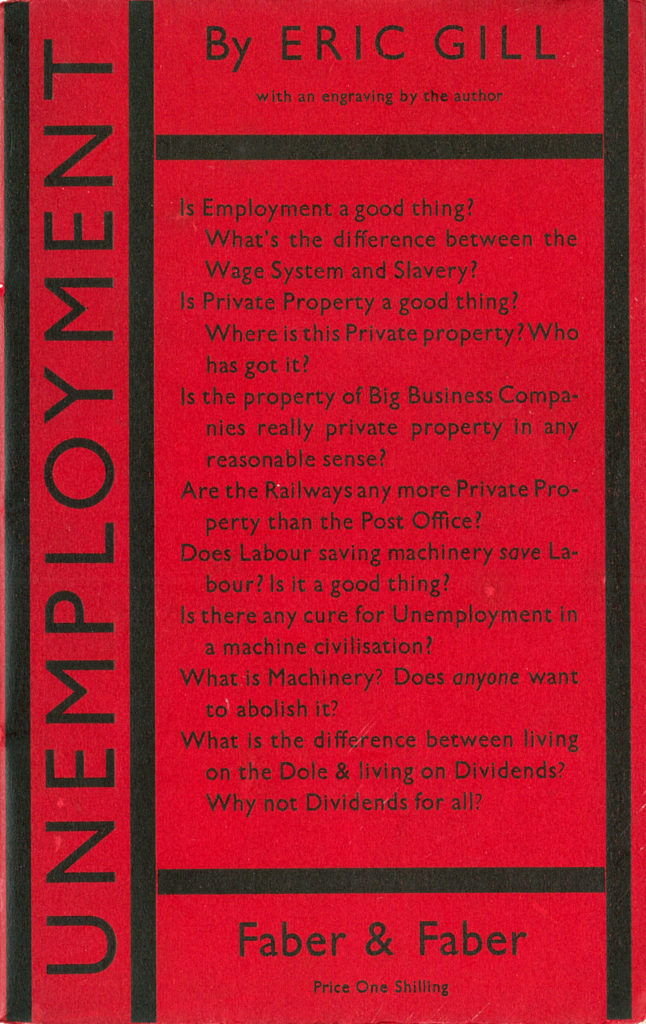

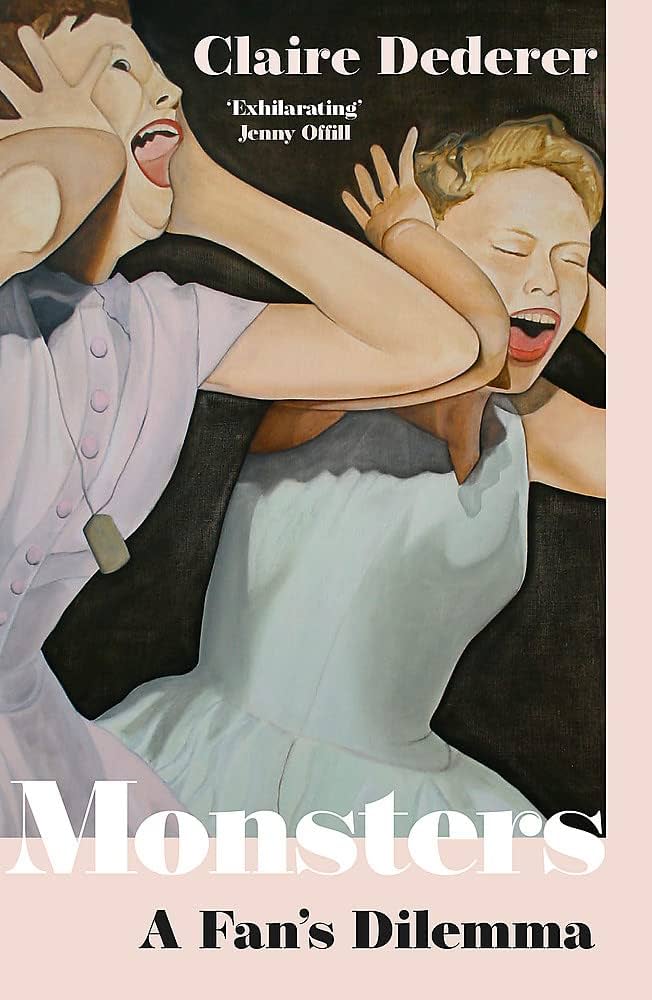

This:

Perhaps to be coupled with this:

*

And ideally throupled with this. 😉

Letters to the Editor: Backyard Chickens Come Home to Roost

You know Hilaire Belloc, don’t you? He wrote Cautionary Tales for Children in which naughty children are joyously dispatched by fire, skewering, and devourment by lions.

But he also wrote The Servile State, a 1912 critique of Big Business and its relationship with the State. A problem with this relationship, Belloc writes, is that it builds a nation of grudging, demoralised Wage Slaves instead of engaged, independent-minded craftspeople. He was right, obviously.

And the solution he proposes for systemically ending Wage Slavery is… private property ownership.

I’m yet to decide if that’s an excitingly unconventional position or a drearily conventional one. Every Muggle in Britain today seeks to own property, but those who pursue it most fervently (those who become landlords for example) don’t generally want to end Wage Slavery. So. I’m interested.

“If we do not restore the Institution of Property,” he writes at the very top, “we cannot escape restoring the Institution of Slavery; there is no third course.”

Perhaps he’s saying that, once rent is out of the picture, a person approaches financial independence and can get on with something meaningful instead of toiling full-time. I wonder if Belloc (much like Keynes, who predicted we’d all be on a 15-hour work week by now) did not foresee the delinquent appetites of humans under capitalism. Plenty of people who pay off their mortgage but continue to toil, usually with some other thing in the balance — like a pension or even another mortgage for a bigger or second house.

I’ll say more about Belloc’s argument another time when I’ve come to firmer grips with it. Reader’s voice: what a cop out! It reminds me, however, that we’ve not said anything about the “renting versus owning” issue for a while.

*

As many of you know, my partner and I recently bought our first apartment after decades of renting. We enjoyed renting and it was our preference: if you see your landlord not as a boss or superegoic parent figure but as a skivvy paid to keep you housed and to repair your washing machine when it breaks, it becomes a most amenable relationship.

Several rent hikes (or pay rises for our skiv), alas, made our continued tenancy unaffordable. Our rent doubled over six years.

The fun of renting is to aristocratically dismiss your worries about the future, but the cost expanded so exorbitantly that we found ourselves worried not just about the future but about the present. This doesn’t mean “ownership wins.” It means the UK rental situation is fucked up beyond measure.

When we bought the flat two years ago, I grumbled about it in the newsletter and got some email responses on the subject. So let’s run a themed edition of Letters to the Editor.

To send a letter to the editor, simply write in. You’ll get a reply and we’ll anonymise any blogged version.

Friend Ian’s email was amusingly useless:

Hi Rob,

Hope this finds you well. As a communist homeowner I have strong and conflicted views on this, which I meant to share with you following your first email about it, but, obviously, I never got round to it.

[I also wanted] to let you know that I might have clicked on the grieving face emoji in response to how I feel about your Kickstarter campaign. Rest assured this was in error: I intended to click on the happy face, but I’m in a bit of a vaccine fever at the moment, so not at my maximum competence.

Cheers,

Ian

PS: ‘grieving face emoji’ was an autocorrect typo; I meant to type ‘frowning face emoji’.

Ah, the vaccine. Heady days. Ian doesn’t go into detail about his conflicted feelings as a communist homeowner, but I imagine they are something like “property is theft but, since we’re economically bullied into committing theft, what are you going to do?”

Reader X wrote:

You may need to clarify – renting for 1000 quid vs. buying for 100 apiece?? Are house prices in Scotland that reasonable?! If so, sign me right up. I’ll draw on my escape fund and we can set up a nice escapological homestead littered with tinkering shops and garden space.

After the rent hikes, our old place was nearing £1,000 a month to rent. It was the cheapest flat on a fairly posh street where rental prices are now around £1,200. Our current mortgage repayments by comparison are £180 a month each (£360 total). I don’t know how typical this is: we wrestled a great deal out of the bastards at the bank. It’s a fixed-rate mortgage too, so we have not yet been hit by the inflation apocalypse.

Property prices in our city are more reasonable than in London though. All I can say is: don’t live in capital cities. Move north! I know the bright lights are exciting but (in my opinion) it’s better to live cheaply in a “workshop city” like Glasgow or Manchester or Liverpool where culture is produced rather than merely sold. To oligarchs.

Reader Q wrote:

As I start to get a bit older I am more in favour of buying. One can quarrel in the mind over the economics until your backyard chickens come to roost. But, you most likely can’t have backyard chickens when you’re a renter.

As renters, our equivalent of a backyard was a spare room. Readers of The Good Life for Wage Slaves will know the importance I place on having ample space for creative work and being able to accommodate friends. We could not afford to buy a place with a spare room though. We sacrifices the spare room to the reduced cost. And we still don’t have a garden. Not that we particularly want one.

and continued:

My current rented abode is filled with the half-finished intentions and tastes of another couple looking to make a few bucks after upgrading their digs. Sometimes I get a weird eerie feeling like I’m living in someone else’s past with their poor choice of cheap plastic jellyfish chandelier and thick purple wallpaper. But that’s the price of freedom, baby.

Now this I relate to. Our rental was supposedly “unfurnished” but it still came with the landlord’s filthy old roller blinds, lighting fixtures, and tasteless decorative curly things on the ends of the curtain rails. We unscrewed everything on Day One, stashing them away in the flat’s least-useful cupboard. For all we know, the former tenants did the same and these things go up and come down again with every tenant. See also the fireplace and the hole.

*

For more on “rent versus ownership” and other thoughts about homelife, please buy The Good Life for Wage Slaves to help pay my mortgage.

Yellow Bellies

This is from a Twitter feed of interesting nuggets from science and history:

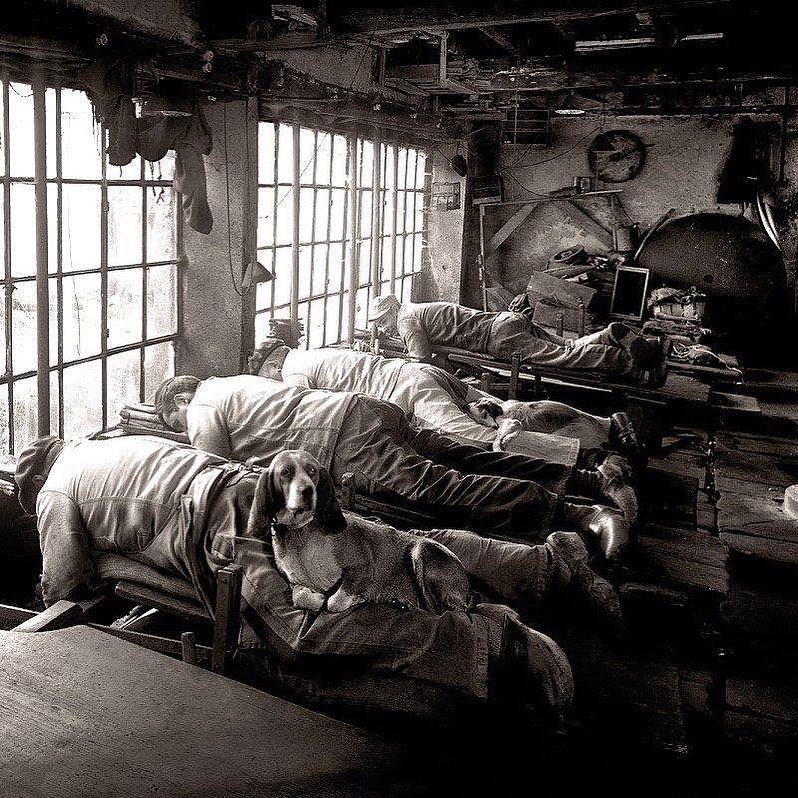

This photo from 1902 shows French knife grinders. They would work on their stomachs in order to save their backs from being hunched all day.

Finally an alternative to those ridiculous standing desks!

They were also encouraged to bring their dogs to work to keep them company and also act as mini heaters by having them rest on their owners’ legs.

So office doggos aren’t a new thing after all.

They were also called ventres jaunes (“yellow bellies” in English) because of the yellow dust that would be released from the grinding wheel.

Better a yellow belly than a brown nose. Bring back the literal grind!

*

An Escapologist’s Diary: Part 73. No Mood for Work.

We’re back from our holiday and, while my partner has leapt directly into her work, I am in NO MOOD FOR IT. I miss the sunshine and the food and the beer and the leisurely strolling. I could do some of that here in Glasgow, I suppose, but there’s work to be done and I do miss Montreal.

I’m still wearing the linen trousers and white cotton shirt with the sleeves rolled up that I bought there to keep cool, even though they should really go in the wash now. I’m keeping the vacation spirit if not alive then at least on life support.

I keep thinking “I must need my head examining for leaving Montreal in the first place” but then I remember the long winters and the difficulties I had making money there and our lack of friends in the city. Le sigh. It’s Glasgow or bust! Scotland is our ecological niche.

The printers proof of my novel was supposed to be waiting for me at home but, to my confusion, there was no sign of it. After some chasing it with the printer and the delivery company it was found by a nice man at a storage depot. At least it had not been returned to sender, but this was still an unnecessary nuisance. I had to wait another day for it to be redelivered. This book seems to be cursed.

Now that I have the proof, I’m not happy enough with it. It looks decidedly “print on demand” with too-white paper and too-narrow margins. The typeface, which looked excellent on the screen, looks weird and probably too big so I might have to reset the whole thing. I put a huge amount of thought into the typesetting and it looks great in PDF so I’m a bit confused and slightly crushed.

The point of a printers proof is to spot things you want to change before printing hundreds of copies so at least I can do something about these problems, but I wasn’t expecting the job to need so many changes. I’m finding this a tad dispiriting. The book is already over two years late and every time I say “now it’s finished” another problem crops up. It’s additionally upsetting given that the motivation (in part) for writing a novel is that it would be easier than writing non-fiction: no research or interviewees, few other parties to please, just me and my imagination in a quiet room. It didn’t turn out that way at all. I had to do two major rewrites after friends told me there were problems with it. Then I wasted two years trying to find a publisher. Then I had to produce it all myself. And now I finally have a copy in hand it still isn’t right.

Reasonably, I know that all I have to do is make a list of the required fixes and then to patiently work my way through the list. The actual changes will only take a few days. But my morale is unusually low today and I wish I was still on holiday. Oh why oh why can’t I still be on holiday?!

Don’t worry, I’ll be back on the horse tomorrow, I’m sure. Today I will read and drink coffee and wallow in my abysmal failures.

*