Doing the right thing, and ‘doing it anyway’: the case of Chiune Sugihara

Sam emails to tell me about Chiune Sugihara, a Japanese diplomat based in Lithuania during WWII. He wrote exit visas for six-thousand Jews (putting them through on his signature alone; an act which could have gotten him and his family executed for treason in Japan) because he got tired of waiting for Tokyo bureaucracy to get back to him.

This keys into my thing about ‘doing it anyway’ when inefficient bureaucracy fails to grant permission (see On Autonomy in Issue 3). Try doing anything of worth and they’ll set a million hoops for you to jump through, often prohibiting the entire venture. Ask for forgiveness, not permission.

In this case, Chiune Sugihara saw that there was a moral imperative to act without permission. With hindsight he obviously did the right thing, but it must have taken superior nerve to snub the authorities in this way and risk being killed for treason. He says:

You want to know about my motivation, don’t you? Well. It is the kind of sentiments anyone would have when he actually sees refugees face to face, begging with tears in their eyes. He just cannot help but sympathize with them. Among the refugees were the elderly and women. They were so desperate that they went so far as to kiss my shoes, Yes, I actually witnessed such scenes with my own eyes. Also, I felt at that time, that the Japanese government did not have any uniform opinion in Tokyo. Some Japanese military leaders were just scared because of the pressure from the Nazis; while other officials in the Home Ministry were simply ambivalent.

People in Tokyo were not united. I felt it silly to deal with them. So, I made up my mind not to wait for their reply. I knew that somebody would surely complain about me in the future. But, I myself thought this would be the right thing to do. There is nothing wrong in saving many people’s lives….The spirit of humanity, philanthropy…neighborly friendship…with this spirit, I ventured to do what I did, confronting this most difficult situation—and because of this reason, I went ahead with redoubled courage.

Issue 6 (I know, Issue 5 isn’t out yet, but it’s being printed as we speak) will be about Escapological morals. It will be called A Rebours.

Towards Internationalism

A challenge for the mobile Escapologist is dealing with bureaucratic systems that that weren’t built to cater for ‘foreigners’.

I’ve mentioned before how I don’t like parochialism. We all occupy the same brilliant world, and the sooner we start to treat the planet’s population as a whole; and ‘their’ problems as ‘our’ problems, the better. Ian Hamilton Finlay once described a country as “an imaginary place recognised only by bumpkins and bureaucrats”. Parochialism stands in the way of the longer-term human endeavor.

That’s probably the most hippie/yippie thing I’ve ever said, but I back the remark with a passion. I’m not suggesting we work towards a single homogenised world culture and language: that would be weird (and impossible). But I think we need to remember, especially in the age of the Internet, that everything we do is part of an interconnected, globe-spanning human project.

I spent most of yesterday morning writing a page for Kickstarter.com in an attempt to raise funding for an exciting creative project. Kickstarter – a peer-to-peer funding site – is a brilliant concept and so I spent a couple of days going through the proverbial ‘abandoned ideas’ file, looking to resurrect projects of merit.

Alas, I am of British origin and the website serves American creatives only. I didn’t realise this until I’d completed a dynamic proposal complete with an artistic .JPG and a video clip, and finally came to courting the payments system. There’s nothing on the Kickstarter homepage that suggests American exclusivity. There are even spotlighted projects on the homepage based in South America and Europe and Japan. But those seemingly international projects, I now learn, are kickstarts for Americans abroad.

To annoy me further, I’d already waited two days to get the go-ahead from Kickstarter HQ, who (to their credit) vet each proposal that comes their way. Why did they accept my proposal if they knew I was non-American? My profile describes me as “A British writer and performer”. My location was set to “Glasgow, Scotland”.

Thankfully I’ve found a similar service called IndieGoGo, which seems to have a more international outlook. Hopefully, most of yesterday’s work can be migrated to this website instead. I’ll let you know if anything comes of it.

When I emailed Kickstarter to ask why I wasn’t able to enter my British or Canadian bank details, they replied with a perfectly civil explanation starting with “We are thankful for the international interest! But for the time being… etc etc”. The exclamation mark speaks volumes. International interest! The very thought! Hohoho. I’ve come up against this before. I once proposed an academic article about ancient Chinese libraries to a UK-based library journal. “I think that’s a bit beyond our remit!” was the chuckled response. Why? Because China is far away from where you’re currently sitting? This journal is circulated internationally via the web, and there is nothing about the its remit, as far as I can see, specifying an exclusive interest in British library history but the suggestion of anything otherwise was a bizarre non-sequitur.

I was prompted to write this post because I was irritated by Kickstarter’s exclusive policy and the time I’d wasted in discovering it. But I do whole-heartedly believe that anything online should address the entire planet (or at least make it clear from the get-go when addressing a specific group of the global population).

We’re slowly getting there, I think. Wikipedia moderators, for instance, come down quite hard on non-universalized articles. We do our best here at New Escapologist too: for a long time now, the contributor guidelines to have begged for an international outlook wherever possible.

I think there’s going to be some kind of massive fallout soon, regarding parochial television programming. Recent international complaints about the ignorant twats at Top Gear; and the unfortunate confusion at QI are case studies in what will soon surely be a larger issue. A TV production company may intend to make a product primarily for a native audience (in the BBC’s case, that of Great Britain) but it mustn’t forget that this material will eventually be broadcast the world over. A kind of internationalisation (or at least decent sensitivity toward other cultures) is required. It goes back to the comedian’s litmus test against offensiveness: would you tell your Irish joke in the presence of an Irish person? If you wouldn’t, then you should probably scrap it. We can only imagine what those future extra-terrestrials will think when they finally intercept our TV signals from the ’60s.

As I say though, I think we are slowly getting there. The latest Doctor Who episodes, produced in a British-Canadian collaboration, have a delightfully British quality but don’t cause mass offense overseas either. This is partly because of the collaborative way it is funded; partly because it is designed to be a lucrative export; and partly because the producers of speculative fiction are, by definition, a forward-looking bunch.

At dinner with a Canadian friend in Scotland last week, we discussed how our language had changed since we’d been working in each other’s countries of origin. She had acquired lots of English and Scottish expressions and I had picked up some North Americanisms. Initially we confessed to trying to ‘check’ those turns of phrase for want of seeming pretentious at home; but we eventually agreed “Fuck it, we’re International people, right?”

Parochial language is not a crime. I just think it’s an indicator of a certain kind of geographical solipsism that is better suited to another century. Old morals, old work ethics and old turns of phrase are slowing us down as a species.

Alain de Botton in Issue 5

The strangest thing about the world of work isn’t the long hours we put in or the fancy machines we use to get it done; take a step back and perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of the work scene is in the end psychological rather than economic or industrial. It has to do with our attitudes to work, more specifically the widespread expectation that our work should make us happy, that it should be at the centre of our lives and our expectations of fulfilment. The first question we tend to ask of new acquaintances is not where they come from or who their parents were, but what they do. Here is the key to someone’s identity and esteem. It seems hard to imagine being able to feel good about yourself or knowing who you were without having work to get on with.

Alain de Botton kindly granted us an interview for Issue Five. We posted a little excerpt at the School of Life blog.

Issue 5 is now available to pre-order at the shop.

Event: “Robert Wringham and the Chrono-Synclastic Infundibulum”

As a piece of performance art, I am making myself available to the public, every Wednesday noontime for the next three months.

As if at the whim of a chrono-synclastic infundibulum, I will appear at Glasgow’s Kibble Palace between 12:00 and 13:00 every Wednesday until the end of May.

You’ll find me sitting near the statue of “King Robert and his Monkey”.

According to the plaque at the foot of the statue, “[Robert] was an arrogant king who was deposed by an angel, stripped of his robes, and forced to assume the role of a jester, with only a monkey for a friend.”

Come and meet me. The words “Hello, Robert” will activate me and, I’ll do one of three things:

1. I’ll casually talk with you until 13:00 (or until you leave);

2. I’ll read a single random passage from Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg (the book from which I take my name);

3. I’ll tell you a short anecdote about my monkey, whose name is Daniel Godsil;

4. I’ll walk you around the main circle of the Kibble Palace, telling a made-up lie about the history of each statue. (This is the star prize. Not many people will receive the honour of this variation).

I’ll also have copies of New Escapologist with me if you’d like to buy one.

This supernatural occurrence is unsanctioned and has nothing to do with Glasgow Botanic Gardens or Glasgow City Council. Tell your friends.

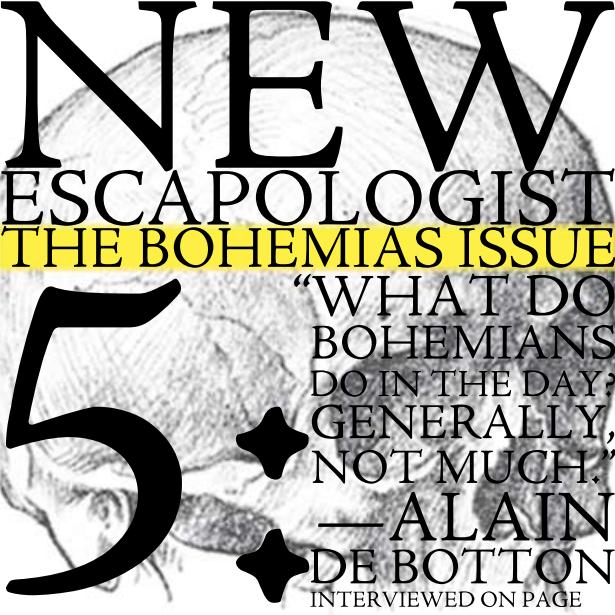

Issue 5 cover

The keen-eyed among you have noticed the cover image of Issue 5 at the shop.

Well, here it is. It’s our first ever departure from the established ’emergency exit’ masthead.

The really keen-eyed among you will notice the lack of a page number for the Alain de Botton interview in the bottom right-hand corner. That’s because this image is actually a draft mock-up. It gives an idea of how the cover of the fifth issue will look though. I hope you like it.

The cover price is yet to be confirmed. To ensure your copy for £6, pre-order it here.

An Escapologist’s Diary. Part 23.

Bleedin’ ‘ek, I’m only back in ole’ Blighty!

Yes, I have returned to Britain, and Samara will join me in a month’s time, after her stint at the Scope Art Show in NYC. We’re going to live here for six months, ostensibly doing the same things we were doing in Montreal, but with the company of our Glasgow chums instead of the Pepsi-drinking weirdos of Montreal.

I flew from Pierre Elliott Trudeau to Birmingham International on Friday. I found myself unable to sleep on the plane. To occupy myself, I watched Inside Job on the inflight entertainment system and, while trying to sleep, deranged myself with questions like ‘How many airplanes have I been on?’ (I think it’s 47).

I’ve been at my parents’ house in Dudley for a few days, but I spent the whole of Monday in Glasgow, viewing eight different apartments. In the past, I’ve usually viewed two or three flats before committing to one, but since I’d made a special trip this time, I’d lined up a day of bumper-to-bumper viewings. After a run of pretty crapular ground-floor studio apartments, I finally found a decent tenement flat north of the Botanics. I move in on Monday 7th.

Being back in Glasgow was a breath of fresh air. (Not literally, of course. It smells of chips and arses). I think it is my favourite of all cities. If money weren’t an issue, I’d live in Glasgow over anywhere else in the world. I feel very at home among those sandstone tenements.

What on Earth is Coca-Cola?

A weird thing happened today. Reading a book, “Coca-Cola” and “Coke” struck me as truly odd words. There’s something disgusting about the somersault into which your vocal chords are forced when saying “Coca-Cola Coke”, as if you are choking.

I then started to doubt whether Coca-Cola even exists. I know it’s probably the most recognised brand in the whole world, but it has been so long since I’ve seen anything about Coca-Cola or thought about Coca-Cola (much less drank any of it) that another part of my brain questioned whether it was a real thing.

Why did this happen? I see three possible explanations:

1. Coke has become such a ubiquitous brand that we now no longer notice it. It has become like the sky or the concrete of the pavements we walk upon. The marketing ‘event horizon’ between maximum visibility and complete invisibility has been crossed.

2. I spent the last year in Monreal, Quebec: one of the few places in the world where Pepsi consistently outsells Coke. So true is this fact, that “Pepsi” or “Pepper” has become a mild ethnic slur for French Canadians.

3. My Escapological drive to avoid television and advertising in general has been a success. Being absent from offices where people drink Coca-Cola bought from vending machines (or “Coke machines”) and talk about Coca-Cola as if it were the only thing that gets them out of bed in the morning, is an unanticipated effect of my change in working practices.

I don’t specifically have anything against Coca-Cola. Though I usually drink water or beer in its place, I don’t find it bad to drink. As advertising goes, a high-budget Coca-Cola advert isn’t even that bad. I just haven’t thought about it in such a long time and this, I think, is a little indicator of (and testament to) the Escapological effect of waterproofing yourself against marketing and moving in a slightly different circle to the typical worker-punter. It works to the extent that I questioned the very existence of the most ubiquitous product ever promoted.

Issue 5: contents

I must apologise for the delay on Issue 5, especially to new subscribers who eagerly anticipate this issue as their first print edition. Our notion to upscale to three issues per year, instead of two, may have been a trifle ambitious.

So what’s our excuse? The house staff are extremely busy. Our arts editor, Samara, is representing her company at the prestigious Scope Art Show in New York City; typographer Tim is in Vietnam; and Sub-Editor Reggie is enjoying the London success of his concert musical, Master Flea. Alas, these absent savants are all-important in the finishing stages of a print production. After my edit, it falls to these brilliant and elven creatures to commission the artwork; re-edit, proof-read and typeset the text.

But who cares about lateness? With some excellent writers, illustrators, a new cover format, and an interview with Alain de Botton, Issue 5: The Bohemias Issue may be our best work to date. At an estimated 115 pages, it is certainly our heftiest. A couple more weeks is all we ask.

To tease you a little further, dear reader, here’s a preview of the contents:

Since it’s such a hefty issue, we may have to increase the cover price slightly. If you pre-order now though, you can secure your copy for £6.

GmBH online

One of our kind stockists, GmBH, has recently moved into online trading. Our third and fourth issues are among their stock, as well as lots of other counter-culture, arty and small-press magazines. Worth a look.

How to access any book ever written, for free

These days, I rarely buy books. They’re too much of an encumbrance for my new travel-light philosophy. Even back in my book-buying days, I managed to avoid buying a single boring academic book for my university studies. How? Because I know how to use a library properly. People are sometimes mystified by this. “They never have what I want!” is a popular complaint.

Understanding how to use a library will counter most claims that libraries are too limited in their stock. Most of them are well stocked by expert librarians whose purchasing choices are informed by clever online “current awareness” systems. Tiny parochial libraries might have modest stocks due to funding limitation but even these can work to your advantage if you use them as portals to the Interlibrary Loan system.

Use the catalogue, not the shelf. Whether you’re looking for a specific book (Being and Nothingness by Jean-Paul Sartre) or have a more general request (“Something about Bad Faith“), the online catalogue is the best place to start. You can probably access this from your home Internet connection or by asking a library assistant to search on your behalf (even over the telephone) or from specially-designated terminals in the library building. The catalogue will show you precisely where the book is located and whether it is currently available for you. If the book’s already on loan, you should be able to reserve it, usually at no cost.

Ask a librarian for alternatives. If the library doesn’t own a copy of the book you want, make an official recommendation to a librarian. If the book sounds like it might be useful to people more generally, the librarian might buy a copy for the library, which you’d be able to borrow on arrival. If they remain skeptical, ask whether you can acquire it via Interlibrary Loan. There is a cost attached to this process, which they might ask you to pay. It’s up to you whether you pay this or visit a different library. Sometimes, a librarian will be able to search other libraries for you using a database like WorldCat or COPAC.

Be a member of several library systems. Your public library will be part of a wider network of libraries, to which you will also be able to borrow. For example, if you’re a member of Dudley Public Library in the British West Midlands, you’ll also be a member of the various branch libraries scattered around the borough. Your library card will work in any of these. It’s worth getting a library card, if possible, for another neighbouring public library system too (i.e. Wolverhampton Libraries as well as Dudley Libraries), though whether you can do this will depend on the geographical location of your home.

If your national library (such as the British Library in London or the Library of Congress in Washington) is within commuting distance, I recommend getting a [free] library card to this. Your national library will be the best-stocked library in your country (and if it’s a copyright deposit library, which it probably is, it will have a copy of almost every book published in the last couple of centuries).

Many universities also offer a low-cost membership scheme to members of the non-academic public. You can probably get an annual subscription to your local university for a sum of money. Check their website for details. Remember that their remit is to cater for students and researchers though, so don’t expect them to have copies of the latest Stephen King paperback (though they actually do sometimes).

The more library cards you collect, the greater access you’ll have to the world’s literature. I never felt so rich as I did when contemplating the value of the books to which I’ve had free access in Glasgow’s Mitchell Library or Montreal’s Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Of course, you don’t even need a library card to use the library. If you can’t get borrowers’ rights in a public library, you can still use it as a reference collection. Feel free to stroll into any public library in the Western world and read as many books or periodicals as you like while on the premises. I’m not a member of Westmount Public Library or Atwater Library in Montreal but they’re among my favourite places to spend time when I’m in this city.

If all else fails, use eBay like a lending library. Buy it, read it and immediately relist it (getting your money back in the process).

This article originally appeared in Issue 4 of New Escapologist. I’m posting it in honour of the current library situation in Britain, but if you enjoyed it, please consider buying a copy of Issue 4 or one of our other publications.