Hark, a Bum

I’m totally useless and a drain on society fulfilling no beneficial function whatsoever. I’ll be 50 in one year. I have nothing to show for myself; no addictions, no high blood pressure, no ulcers, no cholesterol problems; no health problems physical or mental other than the occasional guilt over failing to be a great American entrepreneur.

Thus wrote columnist Tom Chartier in “I am a Bum” in 2004. Let’s skip over the obvious smug remark that maybe Tom shouldn’t have anchored his life goals in Conservative Libertarianism. Come over to the light side, Tom. We have fun here.

But, wait, it looks like he comes to that conclusion himself:

I’m a house husband [now]. My job is to hang out with my son. Oh sure, this means I won’t get the penthouse suite, a company limo and will never get to sit with Wayne Gretzky in his luxury box at the Staples Center but I don’t really care. I will also never get to make underlings squirm in terror at the thought of being told their services will no longer be required, but “say hello to the wife and kids and don’t forget the fruit basket on your way out.” Oh sure, it’s a sacrifice but I am willing to make it. Oddly enough, unlike most of the big Kahunas out there standing center-ring running the show, these things don’t give me any satisfaction. I don’t even enjoy humiliating people, ruining lives or squashing bugs. So I guess there’s no point in me running for office but…I don’t care!

Now you’re getting it, Tom.

Chartier eventually escaped to Grand Cayman in the Caribbean where, ironically enough, he found his version of:

the American dream: No job. No taxes. No winters. No smog. No commute. No military. No Wal-Marts. No terrorists. No crime. No Piggly-Wigglys. No war mongers. No Americans. Well, er, there are a few of us here but we’re in the minority. … we’ve all fled something or another for a better life. I certainly have.

A couple of months after posting the above, Chartier claimed that his declaration of bummery has touched a nerve, that “many readers out there seem to be inspired by my total lack of success. Cries for help have poured in from across the land.”

Why, he’s just like me.

And so, in a step-by-step guide to being a bum, which is actually rather wise and very funny, he ends up advocating for minimalism, downsizing, going car-free, contemplation, choosing the right location instead of the default one, binning off the idea of career, and generally taking it easy.

He concludes:

The trick to being a bum is all mental. It’s all up to you to identify what is really important in your life and what is extraneous balderdash.

Then, and only then, you must have the courage and commitment to flush the useless turd blossoms of your life down the swirly bowl and take the plunge. Go West, Middle Aged Man! Go West and fail! Or go East if that works.

*

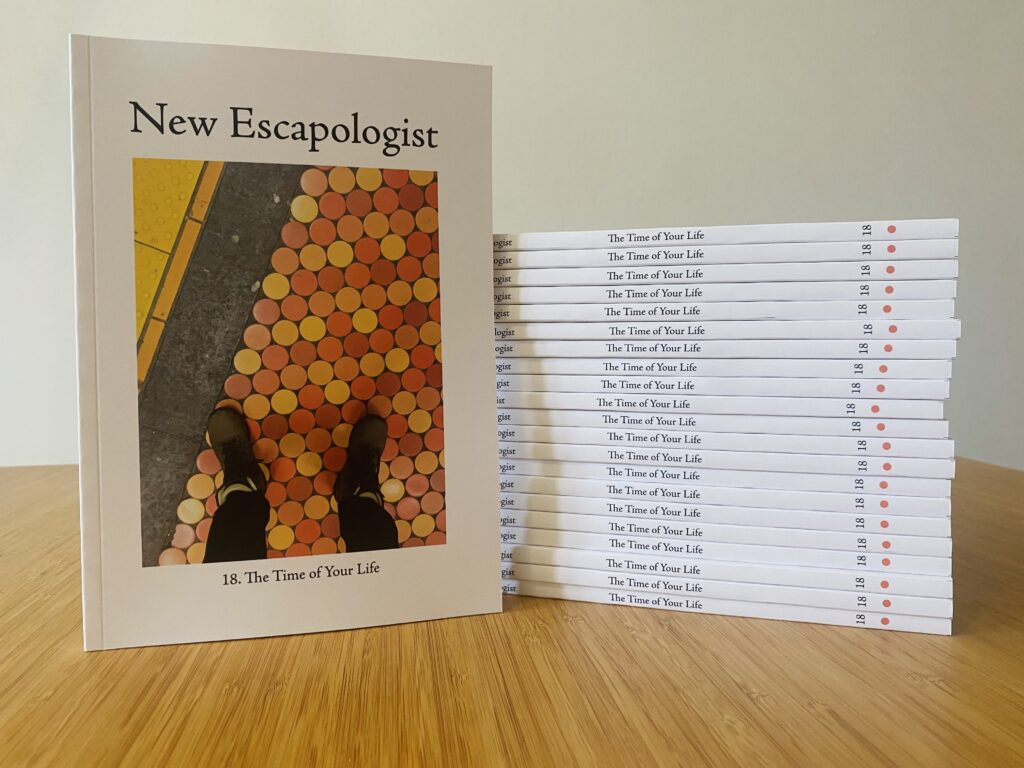

New Escapologist Issue 18 is shipping now. We also have a launch event in Glasgow on 19th November. Come along if you’re nearby!

Smart-Arsed Urbanites

It was supposed to be a clean break from their humdrum existence in a dingy Manchester flat. But all Max Scratchmann and his partner, Chancery, did when they moved to the Orkney Islands was replace one vision of hell with another.

This is very funny. Scratchmann escaped badly and was forced to live with the consequences.

Chucking It All: How Downshifting To A Windswept Scottish Island Did Absolutely Nothing to Improve My Life was supposed to be a light-hearted warning to “smart-arsed urbanites”, tempted by the idea of escaping the rat race, who thought that starting a slower, rustic life somewhere like Provence, Umbria or the Outer Hebrides would somehow find them inner harmony.

but:

the writer’s satirical travelogue about six years among the islanders – whom he describes as “staid, emotionally repressed drunks, stuck in the 1950s” – has so enraged inhabitants of the Scottish archipelago that it has been shelved by his publishers, after threats of legal action.

Whoops.

It’s a reminder, I suppose, to do your research before leaping blindly into an escape. Or at least to visualise it realistically. I mean, what was he expecting? If social life is important to you, a remote island might not be the place to go.

But it’s also a reminder not to be a dick about your new roomies. Not everyone has resolved to escape their own “dingy Manchester flat,” or their equivalent of it.

Still, an adventure is an adventure is an adventure. Scratchmann at least has a story to tell. Even if it had to be pulled from print.

*

New Escapologist Issue 18 is shipping now. We also have a launch event in Glasgow on 19th November. Come along if you’re nearby!

Launch!

Magazine: New Escapologist is the magazine for creative people stuck in a crappy day job and lusting for escape. It’s also for the ones who escaped already. Run away and be free! More info here.

Date: 19th November 2025

Time: 6pm-7:30pm followed by drinks at the Victoria

Venue: Aye-Aye Books, Broadside,123 Allison Street, Glasgow, G42 8NE

Unnecessary eventbrite link? yup.

Walking Across Liechtenstein

Walking through the country was remarkably peaceful, with a kind of quiet atmosphere that makes you lower your voice without thinking. Indeed, a running joke of the trip was that emmy and I would abruptly turn around shush each other. Shhh! Mustn’t disturb the Liechtensteiners or the cows.

Heather Delaney of the Dirtbag Dao has a nice piece in Issue 18 about her American van life.

Since we’re in touch by email, she told me recently about her plan to visit Europe and to walk across Liechtenstein. Well, she only went and bloody did it! Heather explains:

I had decided a couple years back, after walking across England via the Hadrian’s Wall trail, that walking across small countries is a mighty fine way to spend time. Rather than try to bounce around to various sights, you simply stroll your way through the entire land, following paths that are etched in history, designed by pilgrims and locals. Walking across micronations and other tiny countries gives one a sense of oversized accomplishment.

*

New Escapologist Issue 18 (with Heather’s van life piece) is shipping now. We also have a launch event in Glasgow on 19th November. Come along if you’re nearby!

Living Rootless

Living Rootless is the blog of Mzuri, “an introverted woman of a certain age” who “sells her house, gets rid of her stuff, and goes rootless.”

Sounds good to me. She’s been documenting her rootlessness since 2010. That first post reads:

I’ve sold my house. Move-out day is October 15, and, as of today, I don’t yet have a forwarding address.

I’m going rootless.

The following posts document her divestment from stuff. She buys her first laptop to replace her desktop to increase mobility. She sells or gives away or destroys everything she doesn’t need, conducts research. It’s an entire escape, documented.

Each post is short, but there’s hundreds of them each year so they really pile up:

I am staying at friend Kate’s house for a couple of days. This evening, she asked, “Do you have any regrets about selling your house”? I responded, “Not a one.”

One hour later, as Kate is swiftly turning off the water main inside her house, because her pipes had frozen, and burst, and there is water spewing out over the washer and dryer in her garage, she says, “Yeah, I guess not.”

Mzuri is American and her first solo trip was Ethiopia, which strikes me as extremely ambitious and freewheeling. Since then she’s travelled in Mexico, the US, and Guatamala.

Here’s Mzuri on debt, on minimalism, on slow travel, on voluntary simplicity.

*

New Escapologist Issue 18 is shipping now. We also have a launch event in Glasgow on 19th November. Come along if you’re nearby!

Issue 18 Launch Event, 19th November, 6pm, Glasgow

We’re launching Issue 18 of New Escapologist on November 19th, meaning that pre-orders and subscriber copies will be shipped very soon. In fact, we’ve already shipped a few. Maybe you have yours already.

But Red Alert! We’ve had a venue change for the launch event! Pay attention if you’re in/near Glasgow and are planning to come along.

The new venue is Aye-Aye Books, which is now in Broadside at 123 Allison Street, G42 8NE, and looks like this:

Aye-Aye Books are longstanding friends of the magazine, selling the magazine in a prominent location in their shop and everything. They were based in the CCA until very recently, so please don’t make the mistake of going to the CCA or to the previously-announced launch venue, which now looks like this:

Oh dear.

It would have been nice if the owner had told us he’d gone out of business and therefore unlikely to host us as planned, but I suppose he had bigger problems on his hands.

Anyway, Martin from Aye-Aye is a wonderful chap, and I for one am looking forward to helping to warm up his new space. Join us!

Drop in at some point between 6pm-7:30pm for a short reading and some chat, then drinks if we want them at the Victoria bar across the road.

Up Next: Edinburgh Zine Fair 2025

Edinburgh Zine Fair, 1st-2nd November, noon til 5:30/4:30, St. Margaret’s House, 151 London Road, Edinburgh.

I’ll be there to sign books and mags all day on Saturday.

We’ll be represented by our capable young editorial assistant Jack on the Sunday.

Come along if you’re local! Buy a magazine, a book, a badge, or just to say hello.

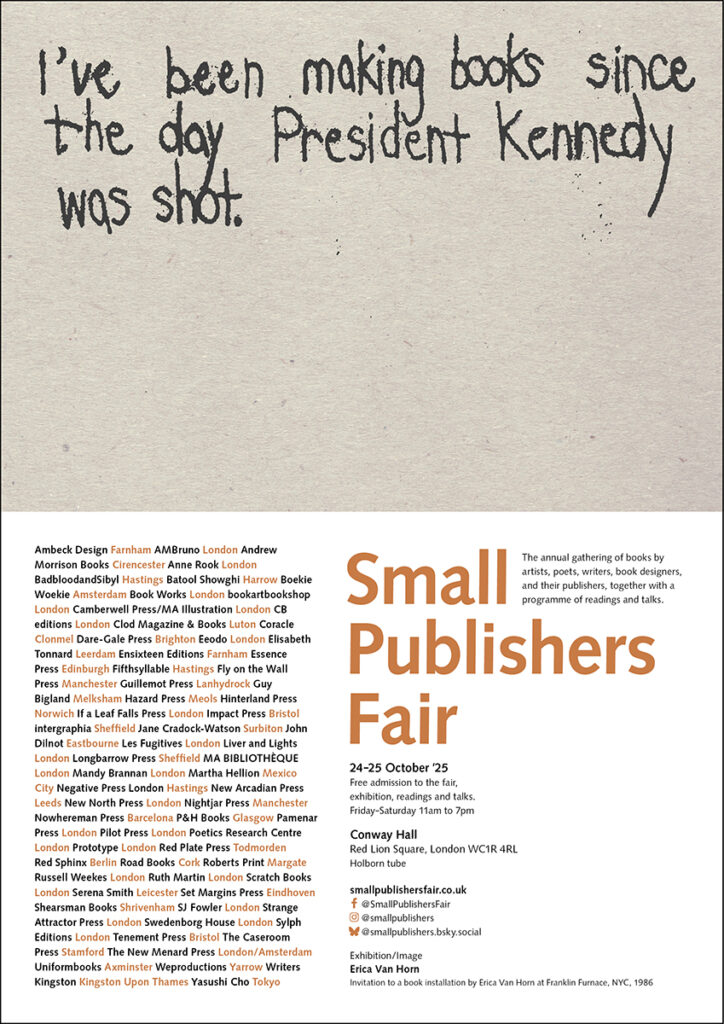

London Small Publishers Fair

Come and see me (editor Robert Wringham) at the P&H Books table at London’s Small Publishers Fair on Friday 24th and/or Saturday 25th October.

This is at Conway Hall and be there for the whole weekend.

I’ll have a limited supply of the brand new New Escapologist Issue 18. This will be the first time the new issue has seen the light of day, ahead of shipping and ahead of our November launch event. It’s a true first look and feels very special. Come along to buy a copy (or collect yours if you’re a subscriber or have already ordered one) or just to say hello.

On the Friday afternoon, I’ll be joined by New Escapologist contributor Dickon Edwards who will sign copies of the magazine and his new book.

On the Saturday afternoon, I’ll be joined by comedian and New Escapologist interviewee John Dowie who, likewise, will sign copies of his new book.

I’ll also have copies of The Good Life for Wage Slaves and will be happy to sign it or indeed anything else you like. I’ll even sign Dickon’s and Dowie’s books if you like. Confuse your friends.

Other incredible publishers will be representing their goods including the amazing Strange Attractor Press (huge fan) and CB Editions, about whom I’ve raved before.

And as if all THAT weren’t enough, Dickon will be celebrating the launch of his book at The Boogaloo pub on Archway Road from 7pm on the Friday night. I’ll be there too, propping up the bar from 7:30pm, so that’s where to be if you’d like to get a drink. I’ll bring a very limited supply of books and mags along too (very limited since this is Dickon’s event).

Please come along! Help to make my schlep from Glasgow worthwhile, get yourself some unique printed goods, and join the fun.

A Promotion or Worse

Meanwhile, in New Zealand again:

Auckland ad man Joshua Jack said he sensed the bad news when he received an email from his agency employer telling him they needed to have a meeting to discuss his role this week. “I thought, it’s either a promotion or worse. I thought it was best to bring in a professional — so I paid $200 and hired a clown.”

As a clown myself, I would hereby like to offer my services to employed New Escapologist readers. $200 NZD plus travel expenses. I’ll sit with you, silently (my style of clowning), in a meeting. I’ll wear a sharp suit and a red nose.

The clown mimed crying as Jack’s employers slid the redundancy paperwork across the table and created a balloon unicorn and poodle to lighten the mood.

“It was sort of noisy, him making balloon animals, so we did have to tell him to be quiet from time to time.”

*

New Escapologist Issue 18 is now available to order for prompt shipping in November.

When It Suddenly Occurred to Me

I love hearing about an epiphany: when people remember the moment they snapped, the precise second they decided enough was enough.

Here’s a beauty from the poet Michael Shann:

September 1989, Liverpool. I was 22 and had just begun an accountancy course that would guarantee a secure career in NHS finance for the next 40 years. It all felt wrong. I should have been in a lecture but was walking up Ranelagh Street towards the Adelphi Hotel when it suddenly occurred to me. I’m a poet.

It’s perfect. He remembers the place, the idea, the feeling:

It struck me with such a blow of truth and clarity that I walked straight down Lime Street to the Central Library, found a place at one of the big reading tables and wrote my first poem.

Did you spot the truly unusual part? It’s the part where he did something about it.

*

New Escapologist Issue 18 is now available to order for prompt shipping in November.